第10章 泛型、Trait 和生命周期

每一个编程语言都有高效处理重复概念的工具。在 Rust 中其工具之一就是 泛型(generics):具体类型或其他属性的抽象替代。我们可以表达泛型的属性,比如它们的行为或如何与其他泛型相关联,而不需要在编写和编译代码时知道它们在这里实际上代表什么。之后,我们讨论如何使用 trait 定义泛型行为的方法。trait 可以与泛型结合来将泛型限制为只接受拥有特定行为的类型,而不是任意类型。最后介绍 生命

每一个编程语言都有高效处理重复概念的工具。在 Rust 中其工具之一就是 泛型(generics):具体类型或其他属性的抽象替代。我们可以表达泛型的属性,比如它们的行为或如何与其他泛型相关联,而不需要在编写和编译代码时知道它们在这里实际上代表什么。

函数可以获取一些不同于 i32 或 String 这样具体类型的泛型参数,就像一个获取未知类型值的函数可以对多种具体类型的值运行同一段代码一样。事实上我们已经使用过第六章的 Option<T>,第八章的 Vec<T> 和 HashMap<K, V>,以及第九章的 Result<T, E> 这些泛型了。本章会探索如何使用泛型定义我们自己的类型、函数和方法!

首先,我们将回顾一下提取函数以减少代码重复的机制。接下来,我们将使用相同的技术,从两个仅参数类型不同的函数中创建一个泛型函数。我们也会讲到结构体和枚举定义中的泛型。

之后,我们讨论如何使用 trait 定义泛型行为的方法。trait 可以与泛型结合来将泛型限制为只接受拥有特定行为的类型,而不是任意类型。

最后介绍 生命周期(lifetimes):一类允许我们向编译器提供引用如何相互关联的泛型。Rust 的生命周期功能允许在更多场景下借用值的同时仍然使编译器能够检查这些引用的有效性而不用借助我们的帮助。

提取函数来减少重复

泛型允许我们使用一个可以代表多种类型的占位符来替换特定类型,以此来减少代码冗余。在深入了解泛型的语法之前,我们首先来看一种没有使用泛型的减少冗余的方法,即提取一个函数。在这个函数中,我们用一个可以代表多种值的占位符来替换具体的值。接着我们使用相同的技术来提取一个泛型函数!通过学习如何识别并提取可以整合进一个函数的重复代码,你也会开始识别出可以使用泛型的重复代码。

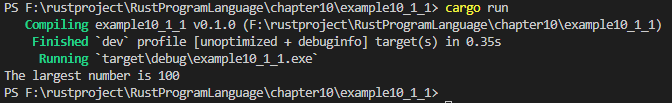

让我们从下面这个寻找列表中最大值的小程序开始,如示例 10-1 所示:

文件名:src/main.rs

// 第10章 参考 示例 10-1:在一个数字列表中寻找最大值的函数

fn main() {

let number_list = vec![34, 50, 25, 100, 65];

let mut largest = &number_list[0];

for number in &number_list {

if number > largest {

largest = number;

}

}

println!("The largest number is {largest}");

}编译运行

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10> cargo new example10_1_1

Creating binary (application) `example10_1_1` package

note: see more `Cargo.toml` keys and their definitions at https://doc.rust-lang.org/cargo/reference/manifest.html

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10> cd example10_1_1

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10\example10_1_1> cargo run

Compiling example10_1_1 v0.1.0 (F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10\example10_1_1)

Finished `dev` profile [unoptimized + debuginfo] target(s) in 0.35s

Running `target\debug\example10_1_1.exe`

The largest number is 100

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10\example10_1_1>

这段代码获取一个整型列表,存放在变量 number_list 中。它将列表的第一个数字的引用放入了变量 largest 中。接着遍历了列表中的所有数字,如果当前值大于 largest 中储存的值,将 largest 替换为这个值。如果当前值小于或者等于目前为止的最大值,变量保持不变,并且代码移动到列表中的下一个数字。当列表中所有值都被考虑到之后,largest 将会指向最大值,在这里也就是 100。

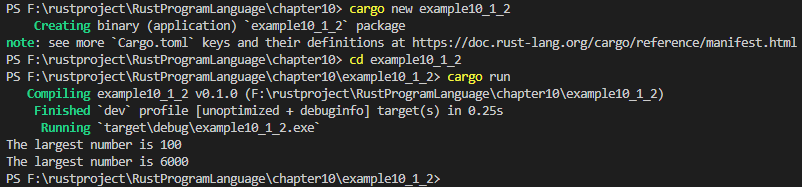

我们的任务是在两个不同的数字列表中寻找最大值。为此我们可以选择重复示例 10-1 中的代码在程序的两个不同位置使用相同的逻辑,如示例 10-2 所示:

文件名:src/main.rs

// 第10章 参考 示例 10-2:寻找两个数组最大值的代码

fn main() {

let number_list = vec![34, 50, 25, 100, 65];

let mut largest = &number_list[0];

for number in &number_list {

if number > largest {

largest = number;

}

}

println!("The largest number is {largest}");

let number_list = vec![102, 34, 6000, 89, 54, 2, 43, 8];

let mut largest = &number_list[0];

for number in &number_list {

if number > largest {

largest = number;

}

}

println!("The largest number is {largest}");

}

编译运行:

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10> cargo new example10_1_2

Creating binary (application) `example10_1_2` package

note: see more `Cargo.toml` keys and their definitions at https://doc.rust-lang.org/cargo/reference/manifest.html

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10> cd example10_1_2

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10\example10_1_2> cargo run

Compiling example10_1_2 v0.1.0 (F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10\example10_1_2)

Finished `dev` profile [unoptimized + debuginfo] target(s) in 0.25s

Running `target\debug\example10_1_2.exe`

The largest number is 100

The largest number is 6000

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10\example10_1_2>

虽然代码能够执行,但是重复的代码是冗余且容易出错的,更新逻辑时我们不得不记住需要修改多处地方的代码。

为了消除重复,我们要创建一层抽象,定义一个处理任意整型列表作为参数的函数。这个方案使得代码更简洁,并且表现了寻找任意列表中最大值这一概念。

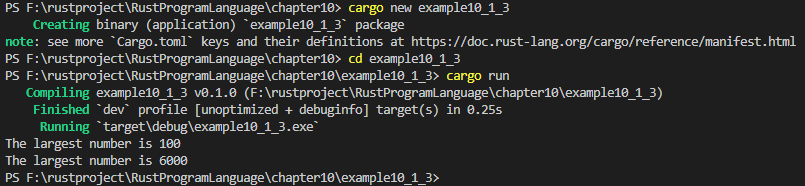

在示例 10-3 的程序中将寻找最大值的代码提取到了一个叫做 largest 的函数中。接着我们调用该函数来寻找示例 10-2 中两个列表中的最大值。之后也可以将该函数用于任何可能的 i32 值的列表。

文件名:src/main.rs

// 第10章 参考 示例 10-3:抽象后的寻找两个数字列表最大值的代码

fn largest(list: &[i32]) -> &i32 {

let mut largest = &list[0];

for item in list {

if item > largest {

largest = item;

}

}

largest

}

fn main() {

let number_list = vec![34, 50, 25, 100, 65];

let result = largest(&number_list);

println!("The largest number is {result}");

let number_list = vec![102, 34, 6000, 89, 54, 2, 43, 8];

let result = largest(&number_list);

println!("The largest number is {result}");

}

编译运行:

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10> cargo new example10_1_3

Creating binary (application) `example10_1_3` package

note: see more `Cargo.toml` keys and their definitions at https://doc.rust-lang.org/cargo/reference/manifest.html

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10> cd example10_1_3

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10\example10_1_3> cargo run

Compiling example10_1_3 v0.1.0 (F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10\example10_1_3)

Finished `dev` profile [unoptimized + debuginfo] target(s) in 0.25s

Running `target\debug\example10_1_3.exe`

The largest number is 100

The largest number is 6000

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10\example10_1_3>

largest 函数有一个参数 list,它代表会传递给函数的任何具体的 i32值的 slice。函数定义中的 list 代表任何 &[i32]。当调用 largest 函数时,其代码实际上运行于我们传递的特定值上。

总的来说,从示例 10-2 到示例 10-3 中代码的修改经历了如下几步:

- 找出重复代码。

- 将重复代码提取到了一个函数中,并在函数签名中指定了代码中的输入和返回值。

- 将重复代码的两个实例,改为调用函数。

接下来我们会使用相同的步骤通过泛型来减少重复。与函数体可以处理任意的 list 而不是具体的值一样,泛型也允许代码处理任意类型。

如果我们有两个函数,一个寻找一个 i32 值的 slice 中的最大项而另一个寻找 char 值的 slice 中的最大项该怎么办?该如何消除重复呢?让我们拭目以待!

10.1 泛型数据类型

我们可以使用泛型为像函数签名或结构体这样的项创建定义,这样它们就可以用于多种不同的具体数据类型。让我们看看如何使用泛型定义函数、结构体、枚举和方法,然后我们将讨论泛型如何影响代码性能。

在函数定义中使用泛型

当使用泛型定义函数时,本来在函数签名中指定参数和返回值的类型的地方,会改用泛型来表示。采用这种技术,使得代码适应性更强,从而为函数的调用者提供更多的功能,同时也避免了代码的重复。

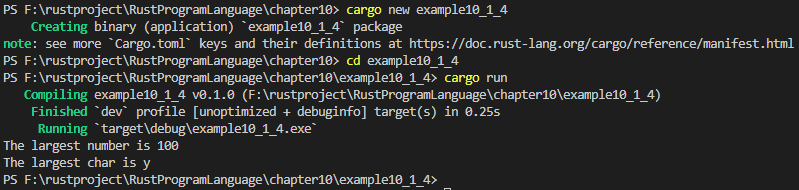

回到 largest 函数,示例 10-4 中展示了两个函数,它们的功能都是寻找 slice 中最大值。接着我们使用泛型将其合并为一个函数。

文件名:src/main.rs

fn largest_i32(list: &[i32]) -> &i32 {

let mut largest = &list[0];

for item in list {

if item > largest {

largest = item;

}

}

largest

}

fn largest_char(list: &[char]) -> &char {

let mut largest = &list[0];

for item in list {

if item > largest {

largest = item;

}

}

largest

}

fn main() {

let number_list = vec![34, 50, 25, 100, 65];

let result = largest_i32(&number_list);

println!("The largest number is {result}");

let char_list = vec!['y', 'm', 'a', 'q'];

let result = largest_char(&char_list);

println!("The largest char is {result}");

}编译运行:

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10> cargo new example10_1_4

Creating binary (application) `example10_1_4` package

note: see more `Cargo.toml` keys and their definitions at https://doc.rust-lang.org/cargo/reference/manifest.html

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10> cd example10_1_4

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10\example10_1_4> cargo run

Compiling example10_1_4 v0.1.0 (F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10\example10_1_4)

Finished `dev` profile [unoptimized + debuginfo] target(s) in 0.25s

Running `target\debug\example10_1_4.exe`

The largest number is 100

The largest char is y

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10\example10_1_4>

largest_i32 函数是从示例 10-3 中摘出来的,它用来寻找 slice 中最大的 i32。largest_char 函数寻找 slice 中最大的 char。因为两者函数体的代码是一样的,我们可以定义一个函数,再引进泛型参数来消除这种重复。

为了参数化这个新函数中的这些类型,我们需要为类型参数命名,道理和给函数的形参起名一样。任何标识符都可以作为类型参数的名字。这里选用 T,因为传统上来说,Rust 的类型参数名字都比较短,通常仅为一个字母,同时,Rust 类型名的命名规范是首字母大写驼峰式命名法(UpperCamelCase)。T 作为 “type” 的缩写是大部分 Rust 程序员的首选。

如果要在函数体中使用参数,就必须在函数签名中声明它的名字,好让编译器知道这个名字指代的是什么。同理,当在函数签名中使用一个类型参数时,必须在使用它之前就声明它。为了定义泛型版本的 largest 函数,类型参数声明位于函数名称与参数列表中间的尖括号 <> 中,像这样:

fn largest<T>(list: &[T]) -> &T {可以这样理解这个定义:函数 largest 有泛型类型 T。它有个参数 list,其类型是元素为 T 的 slice。largest 函数会返回一个与 T 相同类型的引用。

示例 10-5 中的 largest 函数在它的签名中使用了泛型,统一了两个实现。该示例也展示了如何调用 largest 函数,把 i32 值的 slice 或 char 值的 slice 传给它。请注意这些代码还不能编译。

文件名:src/main.rs

// 10.1节 泛型数据类型 参考 示例 10-5:一个使用泛型参数的 largest 函数定义,尚不能编译

// fn largest<T: std::cmp::PartialOrd>(list:&[T]) -> &T { //加上 : std::cmp::PartialOrd 才能编译

fn largest<T>(list:&[T]) -> &T {

let mut largest = &list[0];

for item in list {

if item > largest {

largest = item;

}

}

largest

}

fn main() {

let number_list = vec![34, 50, 25, 100, 65];

let result = largest(&number_list);

println!("The largest number is {result}");

let char_list = vec!['y', 'm', 'a', 'q'];

let result = largest(&char_list);

println!("The largest char is {result}");

}示例 10-5:一个使用泛型参数的 largest 函数定义,尚不能编译

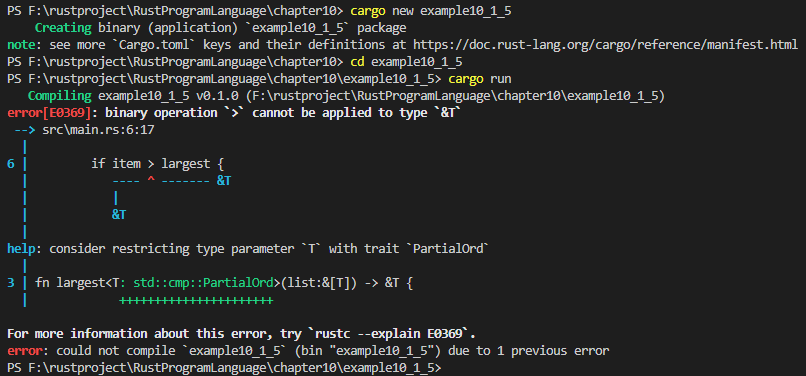

如果现在就编译这段代码,会出现如下错误:

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10> cargo new example10_1_5

Creating binary (application) `example10_1_5` package

note: see more `Cargo.toml` keys and their definitions at https://doc.rust-lang.org/cargo/reference/manifest.html

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10> cd example10_1_5

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10\example10_1_5> cargo run

Compiling example10_1_5 v0.1.0 (F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10\example10_1_5)

error[E0369]: binary operation `>` cannot be applied to type `&T`

--> src\main.rs:6:17

|

6 | if item > largest {

| ---- ^ ------- &T

| |

| &T

|

help: consider restricting type parameter `T` with trait `PartialOrd`

|

3 | fn largest<T: std::cmp::PartialOrd>(list:&[T]) -> &T {

| ++++++++++++++++++++++

For more information about this error, try `rustc --explain E0369`.

error: could not compile `example10_1_5` (bin "example10_1_5") due to 1 previous error

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10\example10_1_5>

帮助说明中提到了 std::cmp::PartialOrd,这是一个 trait。下一部分会讲到 trait。不过简单来说,这个错误表明 largest 的函数体不能适用于 T 的所有可能的类型。因为在函数体需要比较 T 类型的值,不过它只能用于我们知道如何排序的类型。为了开启比较功能,标准库中定义的 std::cmp::PartialOrd trait 可以实现类型的比较功能(查看附录 C 获取该 trait 的更多信息)。依照帮助说明中的建议,我们限制 T 只对实现了 PartialOrd 的类型有效后代码就可以编译了,因为标准库为 i32 和 char 实现了 PartialOrd。

结构体定义中的泛型

同样也可以用 <> 语法来定义结构体,它包含一个或多个泛型参数类型字段。示例 10-6 定义了一个可以存放任何类型的 x 和 y 坐标值的结构体 Point:

文件名:src/main.rs

// 10.1节 泛型数据类型 参考 示例 10-6:Point 结构体存放了两个 T 类型的值 x 和 y

#[derive(Debug)]

struct Point<T> {

x: T,

y: T,

}

fn main() {

let integer = Point{x:5, y:10};

let float = Point{x:1.0, y:4.0};

println!("integer = {:?}, float = {:?}", integer, float);

println!("integer = ({:?}, {:?})", integer.x, integer.y);

println!("float = ({:?}, {:?})", float.x, float.y);

}

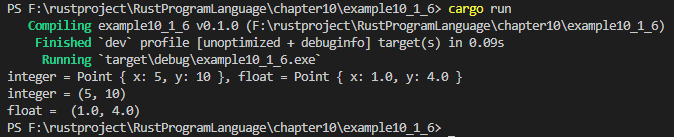

编译运行:

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10> cargo new example10_1_6

Creating binary (application) `example10_1_6` package

note: see more `Cargo.toml` keys and their definitions at https://doc.rust-lang.org/cargo/reference/manifest.html

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10> cd example10_1_6

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10\example10_1_6> cargo run

Compiling example10_1_6 v0.1.0 (F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10\example10_1_6)

Finished `dev` profile [unoptimized + debuginfo] target(s) in 0.09s

Running `target\debug\example10_1_6.exe`

integer = Point { x: 5, y: 10 }, float = Point { x: 1.0, y: 4.0 }

integer = (5, 10)

float = (1.0, 4.0)

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10\example10_1_6>

在结构体定义中使用泛型的语法类似于函数定义中使用泛型。首先,必须在结构体名称后面的尖括号中声明泛型参数的名称。接着在结构体定义中可以指定具体数据类型的位置使用泛型类型。

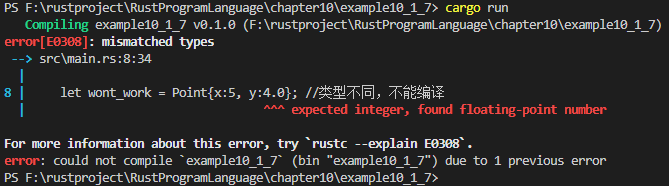

注意 Point<T> 的定义中只使用了一个泛型类型,这个定义表明结构体 Point<T> 对于一些类型 T 是泛型的,而且字段 x 和 y都是 相同类型的,无论它具体是何类型。如果尝试创建一个有不同类型值的 Point<T> 的实例,像示例 10-7 中的代码就不能编译:

文件名:src/main.rs

// 10.1节 泛型数据类型 参考 示例 10-7:字段 x 和 y 的类型必须相同,因为它们都有相同的泛型类型 T

struct Point<T> {

x:T,

y:T,

}

fn main() {

let wont_work = Point{x:5, y:4.0}; //类型不同,不能编译

}示例 10-7:字段 x 和 y 的类型必须相同,因为它们都有相同的泛型类型 T

在这个例子中,当把整型值 5 赋值给 x 时,就告诉了编译器这个 Point<T> 实例中的泛型 T 全是整型。接着指定 y 为浮点值 4.0,因为 y 被定义为与 x 相同类型,所以将会得到一个像这样的类型不匹配错误:

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10> cargo new example10_1_7

Creating binary (application) `example10_1_7` package

note: see more `Cargo.toml` keys and their definitions at https://doc.rust-lang.org/cargo/reference/manifest.html

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10> cd example10_1_7

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10\example10_1_7> cargo run

Compiling example10_1_7 v0.1.0 (F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10\example10_1_7)

error[E0308]: mismatched types

--> src\main.rs:8:34

|

8 | let wont_work = Point{x:5, y:4.0}; //类型不同,不能编译

| ^^^ expected integer, found floating-point number

For more information about this error, try `rustc --explain E0308`.

error: could not compile `example10_1_7` (bin "example10_1_7") due to 1 previous error

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10\example10_1_7>

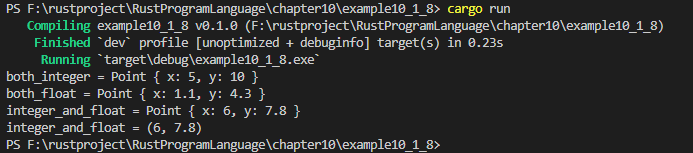

如果想要定义一个 x 和 y 可以有不同类型且仍然是泛型的 Point 结构体,我们可以使用多个泛型类型参数。在示例 10-8 中,我们修改 Point 的定义为拥有两个泛型类型 T 和 U。其中字段 x 是 T 类型的,而字段 y 是 U 类型的:

文件名:src/main.rs

// 10.1节 泛型数据类型 参考 示例 10-8:使用两个泛型的 Point,这样 x 和 y 可能是不同类型

#[derive(Debug)]

struct Point<T, U> {

x: T,

y: U,

}

fn main() {

let both_integer = Point{x: 5, y:10};

let both_float = Point{x:1.1, y:4.3};

let integer_and_float = Point{x:6, y:7.8};

println!("both_integer = {:?}", both_integer);

println!("both_float = {:?}", both_float);

println!("integer_and_float = {:?}", integer_and_float);

println!("integer_and_float = ({:?}, {:?})", integer_and_float.x, integer_and_float.y);

}编译运行:

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10> cargo new example10_1_8

Creating binary (application) `example10_1_8` package

note: see more `Cargo.toml` keys and their definitions at https://doc.rust-lang.org/cargo/reference/manifest.html

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10> cd example10_1_8

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10\example10_1_8> cargo run

Compiling example10_1_8 v0.1.0 (F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10\example10_1_8)

Finished `dev` profile [unoptimized + debuginfo] target(s) in 0.23s

Running `target\debug\example10_1_8.exe`

both_integer = Point { x: 5, y: 10 }

both_float = Point { x: 1.1, y: 4.3 }

integer_and_float = Point { x: 6, y: 7.8 }

integer_and_float = (6, 7.8)

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10\example10_1_8>

现在所有这些 Point 实例都合法了!你可以在定义中使用任意多的泛型类型参数,不过太多的话,代码将难以阅读和理解。当你发现代码中需要很多泛型时,这可能表明你的代码需要重构分解成更小的结构。

枚举定义中的泛型

和结构体类似,枚举也可以在成员中存放泛型数据类型。第六章我们曾用过标准库提供的 Option<T> 枚举,这里再回顾一下:

enum Option<T> {

Some(T),

None,

}现在这个定义应该更容易理解了。如你所见 Option<T> 是一个拥有泛型 T 的枚举,它有两个成员:Some,它存放了一个类型 T 的值,和不存在任何值的None。通过 Option<T> 枚举可以表达有一个可能的值的抽象概念,同时因为 Option<T> 是泛型的,无论这个可能的值是什么类型都可以使用这个抽象。

枚举也可以拥有多个泛型类型。第九章使用过的 Result 枚举定义就是一个这样的例子:

enum Result<T, E> {

Ok(T),

Err(E),

}Result 枚举有两个泛型类型,T 和 E。Result 有两个成员:Ok,它存放一个类型 T 的值,而 Err 则存放一个类型 E 的值。这个定义使得 Result 枚举能很方便的表达任何可能成功(返回 T 类型的值)也可能失败(返回 E 类型的值)的操作。实际上,这就是我们在示例 9-3 用来打开文件的方式:当成功打开文件的时候,T 对应的是 std::fs::File 类型;而当打开文件出现问题时,E 的值则是 std::io::Error 类型。

当你意识到代码中定义了多个结构体或枚举,它们不一样的地方只是其中的值的类型的时候,不妨通过泛型类型来避免重复。

方法定义中的泛型

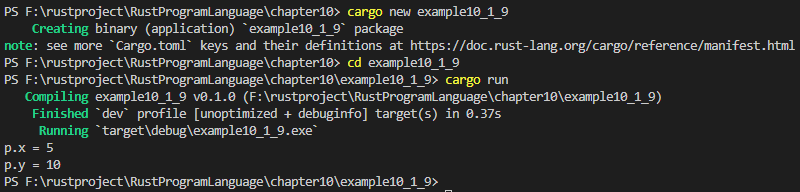

在为结构体和枚举实现方法时(像第五章那样),一样也可以用泛型。示例 10-9 中展示了示例 10-6 中定义的结构体 Point<T>,和在其上实现的名为 x 的方法。

文件名:src/main.rs

// 10.1节 泛型数据类型 参考 示例 10-9:在 Point<T> 结构体上实现方法 x,它返回 T 类型的字段 x 的引用

#[derive(Debug)]

struct Point<T> {

x: T,

y: T,

}

impl<T> Point<T> {

fn x(&self) -> &T {

&self.x

}

fn y(&self) -> &T {

&self.y

}

}

fn main() {

let p = Point{x:5, y: 10};

println!("p.x = {}", p.x());

println!("p.y = {}", p.y());

}

编译运行:

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10> cargo new example10_1_9

Creating binary (application) `example10_1_9` package

note: see more `Cargo.toml` keys and their definitions at https://doc.rust-lang.org/cargo/reference/manifest.html

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10> cd example10_1_9

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10\example10_1_9> cargo run

Compiling example10_1_9 v0.1.0 (F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10\example10_1_9)

Finished `dev` profile [unoptimized + debuginfo] target(s) in 0.37s

Running `target\debug\example10_1_9.exe`

p.x = 5

p.y = 10

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10\example10_1_9>

这里在 Point<T> 上定义了一个叫做 x 的方法用于返回字段 x 中数据的引用。

注意必须在 impl 后面声明 T,这样就可以在 Point<T> 上实现的方法中使用 T 了。通过在 impl 之后声明泛型 T,Rust 就知道 Point 的尖括号中的类型是泛型而不是具体类型。我们可以为泛型参数选择一个与结构体定义中声明的泛型参数所不同的名称,不过依照惯例使用了相同的名称。如果你在impl中编写一个声明泛型类型的方法,那么该方法将在任何类型的实例上定义,无论最终用什么具体类型来替换泛型类型。(译者注:以示例 10-9 为例,impl 中声明了泛型类型参数 T,x 是编写在 impl 中的方法,x 方法将会定义在 Point<T> 的任何实例上,无论最终替换泛型类型参数 T 的是何具体类型)。

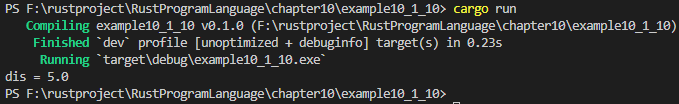

定义方法时也可以为泛型指定限制(constraint)。例如,可以选择为 Point<f32> 实例实现方法,而不是为泛型 Point 实例。示例 10-10 展示了一个没有在 impl 之后(的尖括号)声明泛型的例子,这里使用了一个具体类型,f32:

文件名:src/main.rs

// 10.1节 泛型数据类型 参考 示例 10-10:构建一个只用于拥有泛型参数 T 的结构体的具体类型的 impl 块

#[derive(Debug)]

struct Point<T> {

x: T,

y: T,

}

impl Point<f32> {

fn distance_from_origin(&self) -> f32 {

(self.x.powi(2) + self.y.powi(2)).sqrt()

}

}

fn main() {

let point = Point {x:3.0, y:4.0};

let dis = point.distance_from_origin();

println!("dis = {:?}", dis);

}

示例 10-10:构建一个只用于拥有泛型参数 T 的结构体的具体类型的 impl 块

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10> cargo new example10_1_10

Creating binary (application) `example10_1_10` package

note: see more `Cargo.toml` keys and their definitions at https://doc.rust-lang.org/cargo/reference/manifest.html

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10> cd example10_1_10

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10\example10_1_10> cargo run

Compiling example10_1_10 v0.1.0 (F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10\example10_1_10)

Finished `dev` profile [unoptimized + debuginfo] target(s) in 0.23s

Running `target\debug\example10_1_10.exe`

dis = 5.0

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10\example10_1_10>

这段代码意味着 Point<f32> 类型会有一个方法 distance_from_origin,而其他 T 不是 f32 类型的 Point<T> 实例则没有定义此方法。这个方法计算点实例与坐标 (0.0, 0.0) 之间的距离,并使用了只能用于浮点型的数学运算符。

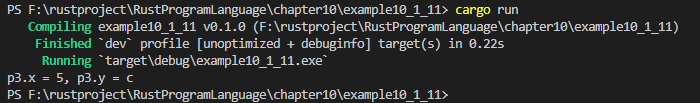

结构体定义中的泛型类型参数并不总是与结构体方法签名中使用的泛型是同一类型。示例 10-11 中为 Point 结构体使用了泛型类型 X1 和 Y1,为 mixup 方法签名使用了 X2 和 Y2 来使得示例更加清楚。这个方法用 self 的 Point 类型的 x 值(类型 X1)和参数的 Point 类型的 y 值(类型 Y2)来创建一个新 Point 类型的实例:

文件名:src/main.rs

// 10.1节 泛型数据类型 参考 示例 10-11:方法使用了与结构体定义中不同类型的泛型

struct Point<X1, Y1> {

x: X1,

y: Y1,

}

impl<X1, Y1> Point<X1, Y1> {

fn mixup<X2, Y2>(self, other: Point<X2, Y2>) -> Point<X1, Y2> {

Point {

x: self.x,

y: other.y,

}

}

}

fn main() {

let p1 = Point{ x: 5, y: 10.4};

let p2 = Point{x:"Hello", y:'c'};

let p3 = p1.mixup(p2);

println!("p3.x = {}, p3.y = {}", p3.x, p3.y);

}编译运行:

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10> cargo new example10_1_11

Creating binary (application) `example10_1_11` package

note: see more `Cargo.toml` keys and their definitions at https://doc.rust-lang.org/cargo/reference/manifest.html

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10> cd example10_1_11

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10\example10_1_11> cargo run

Compiling example10_1_11 v0.1.0 (F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10\example10_1_11)

Finished `dev` profile [unoptimized + debuginfo] target(s) in 0.22s

Running `target\debug\example10_1_11.exe`

p3.x = 5, p3.y = c

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10\example10_1_11>

在 main 函数中,定义了一个有 i32 类型的 x(其值为 5)和 f64 的 y(其值为 10.4)的 Point。p2 则是一个有着字符串 slice 类型的 x(其值为 "Hello")和 char 类型的 y(其值为c)的 Point。在 p1 上以 p2 作为参数调用 mixup 会返回一个 p3,它会有一个 i32 类型的 x,因为 x 来自 p1,并拥有一个 char 类型的 y,因为 y 来自 p2。println! 会打印出 p3.x = 5, p3.y = c。

这个例子的目的是展示一些泛型通过 impl 声明而另一些通过方法定义声明的情况。这里泛型参数 X1 和 Y1 声明于 impl 之后,因为它们与结构体定义相对应。而泛型参数 X2 和 Y2 声明于 fn mixup 之后,因为它们只是相对于方法本身的。

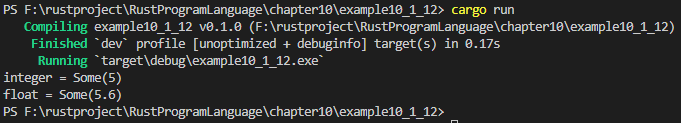

泛型代码的性能

你可能会好奇使用泛型类型参数是否会有运行时消耗。好消息是泛型并不会使程序比具体类型运行得慢。

Rust 通过在编译时进行泛型代码的单态化(monomorphization)来保证效率。单态化是一个通过填充编译时使用的具体类型,将通用代码转换为特定代码的过程。

在这个过程中,编译器所做的工作正好与示例 10-5 中我们创建泛型函数的步骤相反。编译器寻找所有泛型代码被调用的位置并使用泛型代码针对具体类型生成代码。

让我们看看这在标准库的 Option<T> 枚举上是如何工作的:

let integer = Some(5);

let float = Some(5.0);当 Rust 编译这些代码的时候,它会进行单态化。编译器会读取传递给 Option<T> 的值并发现有两种 Option<T>:一个对应 i32 另一个对应 f64。为此,它会将泛型定义 Option<T> 展开为两个针对 i32 和 f64 的定义,接着将泛型定义替换为这两个具体的定义。

编译器生成的单态化版本的代码看起来像这样(编译器会使用不同于如下假想的名字):

文件名:src/main.rs

// 10.1节 泛型数据类型 参考 泛型代码的性能

#![allow(dead_code)] // 在文件顶部禁用整个文件的 dead_code 警告

#[derive(Debug)]

enum OptionI32 {

Some(i32),

None,

}

#[derive(Debug)]

enum OptionF64 {

Some(f64),

None,

}

fn main() {

let integer = OptionI32::Some(5);

let float = OptionF64::Some(5.6);

println!("integer = {:?}", integer);

println!("float = {:?}", float);

}

编译运行:

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10> cargo new example10_1_12

Creating binary (application) `example10_1_12` package

note: see more `Cargo.toml` keys and their definitions at https://doc.rust-lang.org/cargo/reference/manifest.html

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10> cd example10_1_12

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10\example10_1_12> cargo run

Compiling example10_1_12 v0.1.0 (F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10\example10_1_12)

Finished `dev` profile [unoptimized + debuginfo] target(s) in 0.17s

Running `target\debug\example10_1_12.exe`

integer = Some(5)

float = Some(5.6)

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10\example10_1_12>

泛型 Option<T> 被编译器替换为了具体的定义。因为 Rust 会将每种情况下的泛型代码编译为具体类型,使用泛型没有运行时开销。当代码运行时,它的执行效率就跟好像手写每个具体定义的重复代码一样。这个单态化过程正是 Rust 泛型在运行时极其高效的原因。

10.2 Trait:定义共同行为

trait 定义了某个特定类型拥有可能与其他类型共享的功能。可以通过 trait 以一种抽象的方式定义共同行为。可以使用 trait bounds 指定泛型是任何拥有特定行为的类型。

注意:trait 类似于其他语言中的常被称为 接口(interfaces)的功能,虽然有一些不同。

定义trait

一个类型的行为由其可供调用的方法构成。如果可以对不同类型调用相同的方法的话,这些类型就可以共享相同的行为了。trait 定义是一种将方法签名组合起来的方法,目的是定义一个实现某些目的所必需的行为的集合。

例如,这里有多个存放了不同类型和属性文本的结构体:结构体 NewsArticle 用于存放发生于世界各地的新闻故事,而结构体 SocialPost 最多只能存放 280 个字符的内容,以及指示该帖子是新发布的、转发的还是对另一条帖子的回复的元数据。

我们想要创建一个名为 aggregator 的多媒体聚合库用来显示可能储存在 NewsArticle 或 SocialPost 实例中的数据摘要。为了实现功能,每个结构体都要能够获取摘要,这样的话就可以调用实例的 summarize 方法来请求摘要。示例 10-12 中展示了一个表现这个概念的公有 Summary trait 的定义:

文件名:src/lib.rs

pub trait Summary {

fn summarize(&self) -> String;

}示例 10-12:Summary trait 定义,它包含由 summarize 方法提供的行为

这里使用 trait 关键字来声明一个 trait,后面是 trait 的名字,在这个例子中是 Summary。我们也声明 trait 为 pub 以便依赖这个 crate 的其它 crate 也可以使用这个 trait,正如我们见过的一些示例一样。在大括号中声明描述实现这个 trait 的类型所需要的行为的方法签名,在这个例子中是 fn summarize(&self) -> String。

在方法签名后跟分号,而不是在大括号中提供其实现。接着每一个实现这个 trait 的类型都需要提供其自定义行为的方法体,编译器也会确保任何实现 Summary trait 的类型都拥有与这个签名的定义完全一致的 summarize 方法。

trait 体中可以有多个方法:一行一个方法签名且都以分号结尾。

为类型实现trait

现在我们定义了 Summary trait 的签名,接着就可以在多媒体聚合库中实现这个类型了。示例 10-13 中展示了 NewsArticle 结构体上 Summary trait 的一个实现,它使用标题、作者和创建的位置作为 summarize 的返回值。对于 SocialPost 结构体,我们选择将 summarize 定义为用户名后跟帖子全文作为返回值,并假设帖子内容已经被限制为 280 字符以内。

文件名:src/lib.rs

pub struct NewsArticle {

pub headline: String,

pub location: String,

pub author: String,

pub content: String,

}

impl Summary for NewsArticle {

fn summarize(&self) -> String {

format!("{}, by {} ({})", self.headline, self.author, self.location)

}

}

pub struct SocialPost {

pub username: String,

pub content: String,

pub reply: bool,

pub repost: bool,

}

impl Summary for SocialPost {

fn summarize(&self) -> String {

format!("{}: {}", self.username, self.content)

}

}示例 10-13:在 NewsArticle 和 SocialPost 类型上实现 Summary trait

在类型上实现 trait 类似于实现常规方法。区别在于 impl 关键字之后,我们提供需要实现 trait 的名称,接着是 for 和需要实现 trait 的类型的名称。在 impl 块中,使用 trait 定义中的方法签名,不过不再后跟分号,而是需要在大括号中编写函数体来为特定类型实现 trait 方法所拥有的行为。

现在库在 NewsArticle 和 SocialPost 上实现了Summary trait,crate 的用户可以像调用常规方法一样调用 NewsArticle 和 SocialPost 实例的 trait 方法了。唯一的区别是 trait 必须和类型一起引入作用域以便使用额外的 trait 方法。这是一个二进制 crate 如何利用 aggregator 库 crate 的例子:

use aggregator::{SocialPost, Summary};

fn main() {

let post = SocialPost {

username: String::from("horse_ebooks"),

content: String::from(

"of course, as you probably already know, people",

),

reply: false,

repost: false,

};

println!("1 new post: {}", post.summarize());

}这会打印出 1 new post: horse_ebooks: of course, as you probably already know, people。

其他依赖 aggregator crate 的 crate 也可以将 Summary 引入作用域以便为其自己的类型实现该 trait。需要注意的限制是,只有在 trait 或类型至少有一个属于当前 crate 时,我们才能对类型实现该 trait。例如,可以为 aggregator crate 的自定义类型 SocialPost 实现如标准库中的 Display trait,这是因为 SocialPost 类型位于 aggregator crate 本地的作用域中。类似地,也可以在 aggregator crate 中为 Vec<T> 实现 Summary,这是因为 Summary trait 位于 aggregator crate 本地作用域中。

但是不能为外部类型实现外部 trait。例如,不能在 aggregator crate 中为 Vec<T> 实现 Display trait。这是因为 Display 和 Vec<T> 都定义于标准库中,它们并不位于 aggregator crate 本地作用域中。这个限制是被称为相干性(coherence)的程序属性的一部分,或者更具体的说是 孤儿规则(orphan rule),其得名于不存在父类型。这条规则确保了其他人编写的代码不会破坏你的代码,反之亦然。没有这条规则的话,两个 crate 可以分别对相同类型实现相同的 trait,而 Rust 将无从得知应该使用哪一个实现。

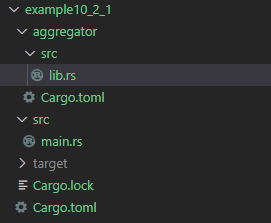

完整的实验代码:

example10_2_1\aggregator\src\lib.rs文件

// 10.2节 参考 示例 10-12, 10-13

// 定义trait

pub trait Summary {

fn summarize(&self) -> String;

}

//为类型实现trait

pub struct NewsArticle{

pub headline:String,

pub location:String,

pub author: String,

pub content:String,

}

impl Summary for NewsArticle {

fn summarize(&self) -> String {

format!("{}, by {} ({})", self.headline, self.author, self.location)

}

}

pub struct SocialPost {

pub username: String,

pub content: String,

pub reply: bool,

pub repost: bool,

}

impl Summary for SocialPost {

fn summarize(&self) -> String {

format!("{}: {}", self.username, self.content)

}

}

example10_2_1\src\main.rs文件

// 10.2节 定义trait, 实现trait 参考 示例 10-12, 10-13

use aggregator::{SocialPost, Summary};

fn main() {

let post = SocialPost {

username: String::from("horse_ebooks"),

content: String::from("of course, as you probably already know, people"),

reply: false,

repost: false,

};

println!("1 new post: {}", post.summarize());

}example10_2_1\Cargo.toml文件

[package]

name = "example10_2_1"

version = "0.1.0"

edition = "2024"

[dependencies]

aggregator = { path = "./aggregator" } # 本地路径依赖编译运行:

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10> cargo new example10_2_1

Creating binary (application) `example10_2_1` package

note: see more `Cargo.toml` keys and their definitions at https://doc.rust-lang.org/cargo/reference/manifest.html

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10> cd example10_2_1

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10\example10_2_1> cargo new aggregator --lib

Creating library `aggregator` package

note: see more `Cargo.toml` keys and their definitions at https://doc.rust-lang.org/cargo/reference/manifest.html

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10\example10_2_1> cargo run

Compiling aggregator v0.1.0 (F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10\example10_2_1\aggregator)

Compiling example10_2_1 v0.1.0 (F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10\example10_2_1)

Finished `dev` profile [unoptimized + debuginfo] target(s) in 0.29s

Running `target\debug\example10_2_1.exe`

1 new post: horse_ebooks: of course, as you probably already know, people

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10\example10_2_1>

默认实现

有时为 trait 中的某些或全部方法提供默认的行为,而不是在每个类型的每个实现中都定义自己的行为是很有用的。这样当为某个特定类型实现 trait 时,可以选择保留或重载每个方法的默认行为。

示例 10-14 中我们为 Summary trait 的 summarize 方法指定一个默认的字符串值,而不是像示例 10-12 中那样只是定义方法签名:

文件名:src/lib.rs

pub trait Summary {

fn summarize(&self) -> String {

String::from("(Read more...)")

}

}示例 10-14:Summary trait 的定义,带有一个 summarize 方法的默认实现

如果想要对 NewsArticle 实例使用这个默认实现,可以通过 impl Summary for NewsArticle {} 指定一个空的 impl 块。

虽然我们不再直接为 NewsArticle 定义 summarize 方法了,但是我们提供了一个默认实现并且指定 NewsArticle 实现 Summary trait。因此,我们仍然可以对 NewsArticle 实例调用 summarize 方法,如下所示:

let article = NewsArticle {

headline: String::from("Penguins win the Stanley Cup Championship!"),

location: String::from("Pittsburgh, PA, USA"),

author: String::from("Iceburgh"),

content: String::from(

"The Pittsburgh Penguins once again are the best \

hockey team in the NHL.",

),

};

println!("New article available! {}", article.summarize());这段代码会打印 New article available! (Read more...)。

为 summarize 创建默认实现并不要求对示例 10-13 中 SocialPost 上的 Summary 实现做任何改变。其原因是重载一个默认实现的语法与实现没有默认实现的 trait 方法的语法一样。

默认实现允许调用相同 trait 中的其他方法,哪怕这些方法没有默认实现。如此,trait 可以提供很多有用的功能而只需要实现指定一小部分内容。例如,我们可以定义 Summary trait,使其具有一个需要实现的 summarize_author 方法,然后定义一个 summarize 方法,此方法的默认实现调用 summarize_author 方法:

pub trait Summary {

fn summarize_author(&self) -> String;

fn summarize(&self) -> String {

format!("(Read more from {}...)", self.summarize_author())

}

}为了使用这个版本的 Summary,只需在为类型实现 trait 时定义 summarize_author 即可:

impl Summary for SocialPost {

fn summarize_author(&self) -> String {

format!("@{}", self.username)

}

}一旦定义了 summarize_author,我们就可以对 SocialPost 结构体的实例调用 summarize 了,而 summarize 的默认实现会调用我们提供的 summarize_author 定义。因为实现了 summarize_author,Summary trait 就提供了 summarize 方法的功能,且无需编写更多的代码。

let post = SocialPost {

username: String::from("horse_ebooks"),

content: String::from(

"of course, as you probably already know, people",

),

reply: false,

repost: false,

};

println!("1 new social post: {}", post.summarize());这会打印出 1 new post: (Read more from @horse_ebooks...)。

请注意,无法从一个方法的重写实现中调用与其同名的默认实现。

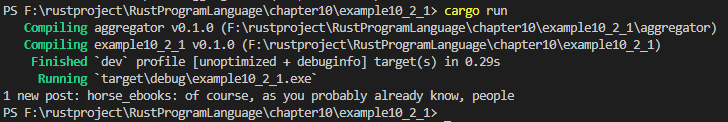

完整的实验代码:

example10_2_2\aggregator\src\lib.rs文件

// 10.2节 参考 示例 10-12, 10-13, 10-14

// 定义trait

pub trait Summary {

// 默认实现

fn summarize(&self) -> String{

String::from("(Read more ...)")

}

fn summarize_author(&self) -> String;

// 调用summarize_author方法

fn summarize2(&self) -> String{

format!("(Read more from {}...)", self.summarize_author())

}

}

//为类型实现trait

pub struct NewsArticle {

pub headline: String,

pub location: String,

pub author: String,

pub content: String,

}

impl Summary for NewsArticle {

//实现trait的summarize_author方法

fn summarize_author(&self) -> String {

format!("NewsArticle@{}", self.author)

}

}

pub struct SocialPost {

pub username: String,

pub content: String,

pub reply: bool,

pub repost: bool,

}

impl Summary for SocialPost {

//实现trait的summarize_author方法

fn summarize_author(&self) ->String {

format!("SocialPost@{}", self.username)

}

}

example10_2_2\src\main.rs文件

// 10.2节 默认实现 参考 示例 10-14

use aggregator::{SocialPost, NewsArticle, Summary};

fn main() {

let article = NewsArticle {

headline: String::from("Penguins win the Stanley Cup Championship!"),

location: String::from("Pittsburgh, PA, USA"),

author: String::from("Iceburgh"),

content: String::from("The Pittsburgh Penguins once again are the best \

hockey team in the NHL."),

};

println!("New article available! {}", article.summarize());

let post = SocialPost {

username: String::from("horse_ebooks"),

content: String::from("of course, as you probably already know, people"),

reply: false,

repost: false,

};

println!("1 new social post:{}", post.summarize2());

}example10_2_2\Cargo.toml文件

[package]

name = "example10_2_2"

version = "0.1.0"

edition = "2024"

[dependencies]

aggregator = { path = "./aggregator" } # 本地路径依赖编译运行:

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10> cargo new example10_2_2

Creating binary (application) `example10_2_2` package

note: see more `Cargo.toml` keys and their definitions at https://doc.rust-lang.org/cargo/reference/manifest.html

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10> cd example10_2_2

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10\example10_2_2> cargo new aggregator --lib

Creating library `aggregator` package

note: see more `Cargo.toml` keys and their definitions at https://doc.rust-lang.org/cargo/reference/manifest.html

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10\example10_2_2> cargo run

Compiling aggregator v0.1.0 (F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10\example10_2_2\aggregator)

Compiling example10_2_2 v0.1.0 (F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10\example10_2_2)

Finished `dev` profile [unoptimized + debuginfo] target(s) in 0.25s

Running `target\debug\example10_2_2.exe`

New article available! (Read more ...)

1 new social post:(Read more from SocialPost@horse_ebooks...)

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10\example10_2_2>

trait作为参数

知道了如何定义 trait 和在类型上实现这些 trait 之后,我们可以探索一下如何使用 trait 来接受多种不同类型的参数。示例 10-13 中为 NewsArticle 和 SocialPost 类型实现了 Summary trait,用其来定义了一个函数 notify 来调用其参数 item 上的 summarize 方法,该参数是实现了 Summary trait 的某种类型。为此可以使用 impl Trait 语法,像这样:

pub fn notify(item: &impl Summary) {

println!("Breaking news! {}", item.summarize());

}对于 item 参数,我们指定了 impl 关键字和 trait 名称,而不是具体的类型。该参数支持任何实现了指定 trait 的类型。在 notify 函数体中,可以调用任何来自 Summary trait 的方法,比如 summarize。我们可以传递任何 NewsArticle 或 SocialPost 的实例来调用 notify。任何用其它如 String 或 i32 的类型调用该函数的代码都不能编译,因为它们没有实现 Summary。

Trait Bound语法

impl Trait 语法更直观,但它实际上是更长形式的 trait bound 语法的语法糖。它看起来像:

pub fn notify<T: Summary>(item: &T) {

println!("Breaking news! {}", item.summarize());

}这种更冗长的写法与上一节的示例等价,但更为冗长。trait bound 与泛型参数声明在一起,位于尖括号中的冒号后面。

impl Trait 很方便,适用于短小的例子。更长的 trait bound 则适用于更复杂的场景。例如,可以获取两个实现了 Summary 的参数。使用 impl Trait 的语法看起来像这样:

pub fn notify(item1: &impl Summary, item2: &impl Summary) {这适用于 item1 和 item2 允许是不同类型的情况(只要它们都实现了 Summary)。不过如果你希望强制它们都是相同类型呢?但如果我们希望强制两个参数必须具有相同类型,则必须使用 trait bound,如下所示:

pub fn notify<T: Summary>(item1: &T, item2: &T) {泛型 T 被指定为 item1 和 item2 的参数限制,如此传递给参数 item1 和 item2 值的具体类型必须一致。

通过+指定多个trait bound

我们也可以指定多个 trait bound。假设我们希望 notify 在 item 上既能使用格式化显示,又能使用 summarize 方法:在 notify 的定义中,指定 item 必须同时实现 Display 和 Summary 两个 trait。这可以通过 + 语法实现:

pub fn notify(item: &(impl Summary + Display)) {+ 语法也适用于泛型的 trait bound:

pub fn notify<T: Summary + Display>(item: &T) {通过指定这两个 trait bound,notify 的函数体可以调用 summarize 并使用 {} 来格式化 item。

通过where简化trait bound

然而,使用过多的 trait bound 也有缺点。每个泛型有其自己的 trait bound,所以有多个泛型参数的函数在名称和参数列表之间会有很长的 trait bound 信息,这使得函数签名难以阅读。为此,Rust 有另一个在函数签名之后的 where 从句中指定 trait bound 的语法。所以除了这么写:

fn some_function<T: Display + Clone, U: Clone + Debug>(t: &T, u: &U) -> i32 {还可以像这样使用 where 从句:

fn some_function<T, U>(t: &T, u: &U) -> i32

where

T: Display + Clone,

U: Clone + Debug,

{这个函数签名就显得不那么杂乱,函数名、参数列表和返回值类型都离得很近,看起来跟没有那么多 trait bounds 的函数很像。

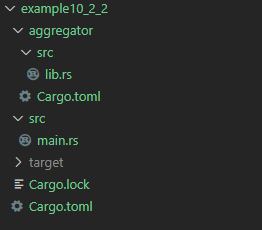

完整的实验代码:

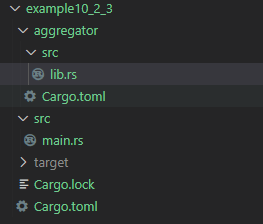

example10_2_3\aggregator\src\lib.rs文件

use std::fmt;

// 10.2节 参考 示例 10-12, 10-13, 10-14

// 定义trait

pub trait Summary {

// 默认实现

fn summarize(&self) -> String{

String::from("(Read more ...)")

}

fn summarize_author(&self) -> String;

// 调用summarize_author方法

fn summarize2(&self) -> String{

format!("(Read more from {}...)", self.summarize_author())

}

}

//为类型实现trait

#[derive(Debug)]

pub struct NewsArticle {

pub headline: String,

pub location: String,

pub author: String,

pub content: String,

}

impl Summary for NewsArticle {

//实现trait的summarize_author方法

fn summarize_author(&self) -> String {

format!("NewsArticle@{}", self.author)

}

}

// 实现 Display trait

impl fmt::Display for NewsArticle {

fn fmt(&self, f: &mut fmt::Formatter<'_>) -> fmt::Result {

write!(f, "Article:{}, Author:{}", self.headline, self.author)

}

}

pub struct SocialPost {

pub username: String,

pub content: String,

pub reply: bool,

pub repost: bool,

}

impl Summary for SocialPost {

//实现trait的summarize_author方法

fn summarize_author(&self) ->String {

format!("SocialPost@{}", self.username)

}

}

example10_2_3\src\main.rs文件

// 10.2节 trait作为参数

use aggregator::{SocialPost, NewsArticle, Summary};

use std::fmt::Display;

// trait作为参数

pub fn notify(item: &impl Summary) {

println!("Breaking news! {}", item.summarize());

}

// Trait Bound语法

pub fn notify2<T: Summary>(item:&T)

{

println!("Breaking news! {}", item.summarize());

}

pub fn notify3(item1: &impl Summary, item2: &impl Summary) {

println!("item1: {}", item1.summarize2());

println!("item2: {}", item2.summarize2());

}

pub fn notify4<T: Summary>(item1: &T, item2: &T) {

println!("item1: {}", item1.summarize2());

println!("item2: {}", item2.summarize2());

}

//通过 + 指定多个 trait bound

pub fn notify5(item: &(impl Summary + Display)) {

println!("通过 + 指定多个 trait bound");

println!("摘要: {}", item.summarize());

println!("显示: {}", item); // 这里自动使用 Display trait

}

//泛型 trait bound

pub fn notify6<T: Summary + Display>(item: &T) {

println!("泛型 trait bound");

println!("摘要: {}", item.summarize2());

println!("显示: {}", item); // 这里自动使用 Display trait

}

//通过where简化trait bound

pub fn notify7<T>(item: &T)

where

T: Summary + Display,

{

println!("泛型版本 通过where简化trait bound");

println!("摘要: {}", item.summarize2());

println!("显示: {}", item); // 这里自动使用 Display trait

}

fn main() {

let article = NewsArticle {

headline: String::from("Penguins win the Stanley Cup Championship!"),

location: String::from("Pittsburgh, PA, USA"),

author: String::from("Iceburgh"),

content: String::from("The Pittsburgh Penguins once again are the best \

hockey team in the NHL."),

};

notify(&article);

let post = SocialPost {

username: String::from("horse_ebooks"),

content: String::from("of course, as you probably already know, people"),

reply: false,

repost: false,

};

notify2(&post);

let post2 = SocialPost {

username: String::from("long_ebooks"),

content: String::from("of course, as you probably already know, people"),

reply: false,

repost: false,

};

notify3(&post, &post2); //类型要一样

notify4(&post, &post2);

notify5(&article);

notify6(&article);

notify7(&article);

}

example10_2_3\Cargo.toml文件

[package]

name = "example10_2_3"

version = "0.1.0"

edition = "2024"

[dependencies]

aggregator = { path = "./aggregator" } # 本地路径依赖编译运行:

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10> cargo new example10_2_3

Creating binary (application) `example10_2_3` package

note: see more `Cargo.toml` keys and their definitions at https://doc.rust-lang.org/cargo/reference/manifest.html

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10> cd example10_2_3

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10\example10_2_3> cargo new aggregator --lib

Creating library `aggregator` package

note: see more `Cargo.toml` keys and their definitions at https://doc.rust-lang.org/cargo/reference/manifest.html

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10\example10_2_3> cargo run

Compiling example10_2_3 v0.1.0 (F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10\example10_2_3)

Finished `dev` profile [unoptimized + debuginfo] target(s) in 0.19s

Running `target\debug\example10_2_3.exe`

Breaking news! (Read more ...)

Breaking news! (Read more ...)

item1: (Read more from SocialPost@horse_ebooks...)

item2: (Read more from SocialPost@long_ebooks...)

item1: (Read more from SocialPost@horse_ebooks...)

item2: (Read more from SocialPost@long_ebooks...)

通过 + 指定多个 trait bound

摘要: (Read more ...)

显示: Article:Penguins win the Stanley Cup Championship!, Author:Iceburgh

泛型 trait bound

摘要: (Read more from NewsArticle@Iceburgh...)

显示: Article:Penguins win the Stanley Cup Championship!, Author:Iceburgh

泛型版本 通过where简化trait bound

摘要: (Read more from NewsArticle@Iceburgh...)

显示: Article:Penguins win the Stanley Cup Championship!, Author:Iceburgh

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10\example10_2_3>

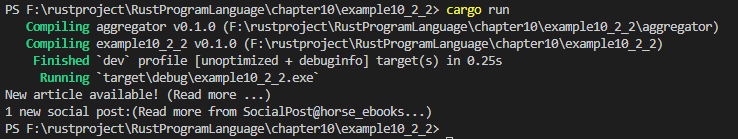

返回实现了trait的类型

也可以在返回值中使用 impl Trait 语法,来返回实现了某个 trait 的类型:

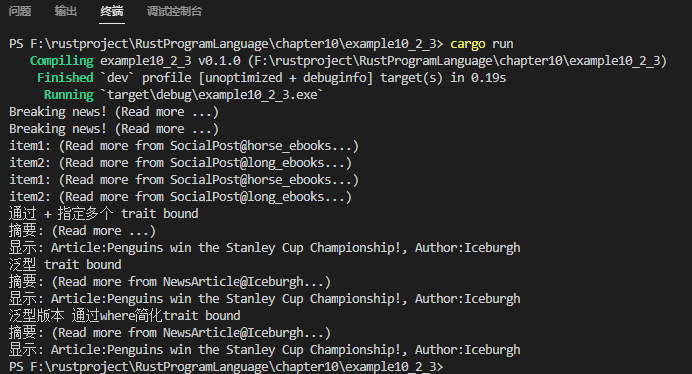

完整的实验代码:

// 10.2节 返回实现了trait的类型

use std::fmt;

// 定义trait

trait Summary {

// 默认实现

fn summarize(&self) -> String{

String::from("(Read more ...)")

}

fn summarize_author(&self) -> String;

}

#[derive(Debug)]

#[allow(dead_code)] //消息除警告

struct SocialPost {

pub username: String,

content: String,

reply: bool,

repost: bool,

}

impl Summary for SocialPost {

//实现trait的summarize_author方法

fn summarize_author(&self) ->String {

format!("SocialPost@{}", self.username)

}

}

// 添加 Debug trait bound

fn returns_summarizable() -> impl Summary + fmt::Debug {

SocialPost {

username: String::from("horse_ebooks"),

content: String::from("of course, as you probably already know, people"),

reply: false,

repost: false,

}

}

fn main() {

let post = returns_summarizable();

println!("post = {:?}", post);

println!("post.uesrname = {:?}", post.summarize_author());

println!("post.summarize = {:?}", post.summarize());

}

编译运行:

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10> cargo new example10_2_4

Creating binary (application) `example10_2_4` package

note: see more `Cargo.toml` keys and their definitions at https://doc.rust-lang.org/cargo/reference/manifest.html

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10> cd example10_2_4

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10\example10_2_4> cargo run

Compiling example10_2_4 v0.1.0 (F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10\example10_2_4)

Finished `dev` profile [unoptimized + debuginfo] target(s) in 0.19s

Running `target\debug\example10_2_4.exe`

post = SocialPost { username: "horse_ebooks", content: "of course, as you probably already know, people", reply: false, repost: false }

post.uesrname = "SocialPost@horse_ebooks"

post.summarize = "(Read more ...)"

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10\example10_2_4>

通过使用 impl Summary 作为返回值类型,我们指定了 returns_summarizable 函数返回某个实现了 Summary trait 的类型,但是不确定其具体的类型。在这个例子中 returns_summarizable 返回了一个 SocialPost,不过调用方并不知情。

返回一个只是指定了需要实现的 trait 的类型的能力在闭包和迭代器场景十分的有用,第十三章会介绍它们。闭包和迭代器创建只有编译器知道的类型,或者是非常非常长的类型。impl Trait 允许你简单的指定函数返回一个 Iterator 而无需写出实际的冗长的类型。

不过这只适用于返回单一类型的情况。例如,这段代码的返回值类型指定为返回 impl Summary,但是返回了 NewsArticle 或 SocialPost 就行不通:

fn returns_summarizable(switch: bool) -> impl Summary {

if switch {

NewsArticle {

headline: String::from(

"Penguins win the Stanley Cup Championship!",

),

location: String::from("Pittsburgh, PA, USA"),

author: String::from("Iceburgh"),

content: String::from(

"The Pittsburgh Penguins once again are the best \

hockey team in the NHL.",

),

}

} else {

SocialPost {

username: String::from("horse_ebooks"),

content: String::from(

"of course, as you probably already know, people",

),

reply: false,

repost: false,

}

}

}这里尝试返回 NewsArticle 或 SocialPost 是不被允许的,原因在于编译器中 impl Trait 语法的实现限制。第十八章的 “顾及不同类型值的 trait 对象” 部分会介绍如何编写这样一个函数。

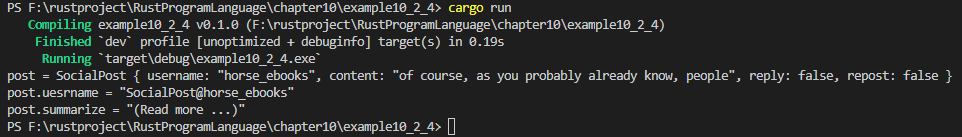

使用trait bound有条件地实现方法

通过使用带有 trait bound 的泛型参数的 impl 块,可以有条件地只为那些实现了特定 trait 的类型实现方法。例如,示例 10-15 中的类型 Pair<T> 总是实现了 new 方法并返回一个 Pair<T> 的实例(回忆一下第五章的 “定义方法” 部分,Self 是一个 impl 块类型的类型别名(type alias),在这里是 Pair<T>)。不过在下一个 impl 块中,只有那些为 T 类型实现了 PartialOrd trait(来允许比较) 和Display trait(来启用打印)的 Pair<T> 才会实现 cmp_display 方法:

// 10.2节 使用trait bound有条件地实现方法 参考 示例 10-15:根据 trait bound 在泛型上有条件的实现方法

use std::fmt::Display;

#[derive(Debug)]

struct Pair<T> {

x: T,

y: T,

}

impl<T> Pair<T> {

fn new(x: T, y: T) -> Self {

Self {x,y}

}

}

//PartialOrd trait(来允许比较) 和Display trait(来启用打印)

impl<T:Display + PartialOrd> Pair<T> {

fn cmp_display(&self) {

if self.x >= self.y {

println!("The largest member is x = {}", self.x);

}else {

println!("The largest member is y = {}", self.y);

}

}

}

fn main() {

let point = Pair {

x: 5,

y: 9,

};

point.cmp_display();

let self_point = Pair::new(5.6, 7.8);

println!("self_point = {:?}", self_point);

println!("self_point = ({:?}, {:?})", self_point.x, self_point.y);

}

编译运行:

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10> cargo new example10_2_5

Creating binary (application) `example10_2_5` package

note: see more `Cargo.toml` keys and their definitions at https://doc.rust-lang.org/cargo/reference/manifest.html

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10> cd example10_2_5

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10\example10_2_5> cargo run

Compiling example10_2_5 v0.1.0 (F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10\example10_2_5)

Finished `dev` profile [unoptimized + debuginfo] target(s) in 0.18s

Running `target\debug\example10_2_5.exe`

The largest member is y = 9

self_point = Pair { x: 5.6, y: 7.8 }

self_point = (5.6, 7.8)

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10\example10_2_5>

也可以对任何实现了特定 trait 的类型有条件地实现 trait。对任何满足特定 trait bound 的类型实现 trait 被称为 blanket implementations,它们被广泛的用于 Rust 标准库中。例如,标准库为任何实现了 Display trait 的类型实现了 ToString trait。这个 impl 块看起来像这样:

impl<T: Display> ToString for T {

// --snip--

}因为标准库有了这些 blanket implementation,我们可以对任何实现了 Display trait 的类型调用由 ToString 定义的 to_string 方法。例如,可以将整型转换为对应的 String 值,因为整型实现了 Display:

let s = 3.to_string();Blanket implementation 会出现在 trait 文档的 “Implementers” 部分。

Trait 和 trait bound 让我们能够使用泛型类型参数来减少重复,而且能够向编译器明确指定泛型类型需要拥有哪些行为。然后编译器可以利用 trait bound 信息检查代码中所用到的具体类型是否提供了正确的行为。在动态类型语言中,如果我们调用了一个未定义的方法,会在运行时出现错误。Rust 将这些错误移动到了编译时,甚至在代码能够运行之前就强迫我们修复问题。另外,我们也无需编写运行时检查行为的代码,因为在编译时就已经检查过了。这样既提升了性能又不必放弃泛型的灵活性。

10.3 生命周期确保引用有效

生命周期是另一类我们已经使用过的泛型。不同于确保类型有期望的行为,生命周期用于保证引用在我们需要的整个期间内都是有效的。

当在第四章讨论 “引用和借用” 部分时,我们遗漏了一个重要的细节:Rust 中的每一个引用都有其生命周期(lifetime),也就是引用保持有效的作用域。大部分时候生命周期是隐含并可以推断的,正如大部分时候类型也是可以推断的一样。类似于当因为有多种可能类型的时候必须注明类型,也会出现引用的生命周期以一些不同方式相关联的情况,所以 Rust 需要我们使用泛型生命周期参数来注明它们的关系,这样就能确保运行时实际使用的引用绝对是有效的。

生命周期注解甚至不是一个大部分语言都有的概念,所以这可能感觉起来有些陌生。虽然本章不可能涉及到它全部的内容,我们会讲到一些通常你可能会遇到的生命周期语法以便你熟悉这个概念。

生命周期避免了悬垂引用

生命周期的主要目标是避免悬垂引用(dangling references),后者会导致程序引用了非预期引用的数据。考虑一下示例 10-16 中的程序,它有一个外部作用域和一个内部作用域。

fn main() {

let r;

{

let x = 5;

r = &x;

}

println!("r: {r}");

}示例 10-16:尝试使用离开作用域的值的引用

注意:示例 10-16、10-17 和 10-23 中声明了没有初始值的变量,所以这些变量存在于外部作用域。这乍看之下好像和 Rust 不允许存在空值相冲突。然而如果尝试在给它一个值之前使用这个变量,会出现一个编译时错误,这就说明了 Rust 确实不允许空值。

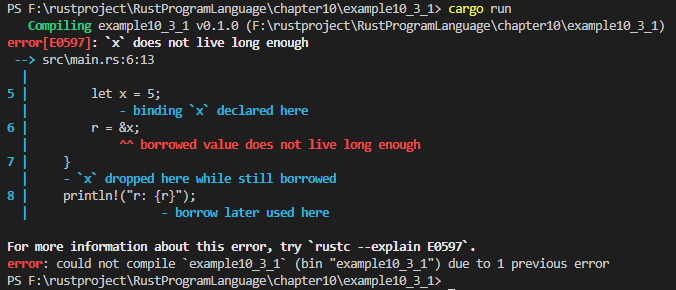

外部作用域声明了一个没有初值的变量 r,而内部作用域声明了一个初值为 5 的变量x。在内部作用域中,我们尝试将 r 的值设置为一个 x 的引用。接着在内部作用域结束后,尝试打印出 r 的值。这段代码不能编译因为 r 引用的值在尝试使用之前就离开了作用域。如下是错误信息:

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10> cargo new example10_3_1

Creating binary (application) `example10_3_1` package

note: see more `Cargo.toml` keys and their definitions at https://doc.rust-lang.org/cargo/reference/manifest.html

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10> cd example10_3_1

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10\example10_3_1> cargo run

Compiling example10_3_1 v0.1.0 (F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10\example10_3_1)

error[E0597]: `x` does not live long enough

--> src\main.rs:6:13

|

5 | let x = 5;

| - binding `x` declared here

6 | r = &x;

| ^^ borrowed value does not live long enough

7 | }

| - `x` dropped here while still borrowed

8 | println!("r: {r}");

| - borrow later used here

For more information about this error, try `rustc --explain E0597`.

error: could not compile `example10_3_1` (bin "example10_3_1") due to 1 previous error

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10\example10_3_1>

变量 x 并没有 “存在的足够久”。其原因是 x 在到达第 7 行内部作用域结束时就离开了作用域。不过 r 在外部作用域仍是有效的;作用域越大我们就说它 “存在的越久”。如果 Rust 允许这段代码工作,r 将会引用在 x 离开作用域时被释放的内存,这时尝试对 r 做任何操作都不能正常工作。那么 Rust 是如何决定这段代码是不被允许的呢?这得益于借用检查器。

借用检查器

Rust 编译器有一个借用检查器(borrow checker),它比较作用域来确保所有的借用都是有效的。示例 10-17 展示了与示例 10-16 相同的例子不过带有变量生命周期的注释:

fn main() {

let r; // ---------+-- 'a

// |

{ // |

let x = 5; // -+-- 'b |

r = &x; // | |

} // -+ |

// |

println!("r: {r}"); // |

} // ---------+示例 10-17:r 和 x 的生命周期注解,分别叫做 'a 和 'b

这里将 r 的生命周期标记为 'a 并将 x 的生命周期标记为 'b。如你所见,内部的 'b 块要比外部的生命周期 'a 小得多。在编译时,Rust 比较这两个生命周期的大小,并发现 r 拥有生命周期 'a,不过它引用了一个拥有生命周期 'b 的对象。程序被拒绝编译,因为生命周期 'b 比生命周期 'a 要小:被引用的对象比它的引用者存在的时间更短。

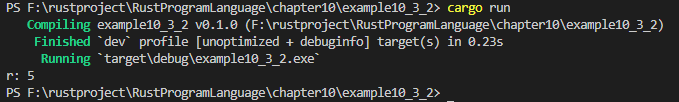

让我们看看示例 10-18 中这个并没有产生悬垂引用且可以正确编译的例子:

// 10.3节 借用检查器 参考:示例 10-18

fn main() {

let x = 5; //----------+----- 'b

// |

let r = &x; //--+-- 'a |

// | |

println!("r: {r}"); // | |

//--+ |

} 编译运行:

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10> cargo new example10_3_2

Creating binary (application) `example10_3_2` package

note: see more `Cargo.toml` keys and their definitions at https://doc.rust-lang.org/cargo/reference/manifest.html

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10> cd example10_3_2

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10\example10_3_2> cargo run

Compiling example10_3_2 v0.1.0 (F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10\example10_3_2)

Finished `dev` profile [unoptimized + debuginfo] target(s) in 0.23s

Running `target\debug\example10_3_2.exe`

r: 5

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10\example10_3_2>

这里 x 拥有生命周期 'b,比 'a 要大。这就意味着 r 可以引用 x:Rust 知道 r 中的引用在 x 有效的时候也总是有效的。

现在我们已经在一个具体的例子中展示了引用的生命周期位于何处,并讨论了 Rust 如何分析生命周期来保证引用总是有效的,接下来让我们聊聊在函数的上下文中参数和返回值的泛型生命周期。

函数中的泛型生命周期

让我们来编写一个返回两个字符串 slice 中较长者的函数。这个函数获取两个字符串 slice 并返回一个字符串 slice。一旦我们实现了 longest 函数,示例 10-19 中的代码应该会打印出 The longest string is abcd:

文件名:src/main.rs

fn main() {

let string1 = String::from("abcd");

let string2 = "xyz";

let result = longest(string1.as_str(), string2);

println!("The longest string is {result}");

}示例 10-19:main 函数调用 longest 函数来寻找两个字符串 slice 中较长的一个

注意这个函数获取作为引用的字符串 slice,而不是字符串,因为我们不希望 longest 函数获取参数的所有权。参考之前第四章中的“字符串 slice 作为参数”部分中更多关于为什么示例 10-19 的参数正符合我们期望的讨论。

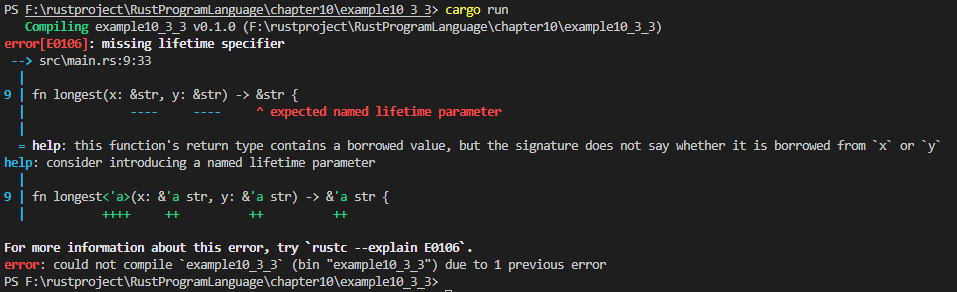

如果尝试像示例 10-20 中那样实现 longest 函数,它并不能编译:

文件名:src/main.rs

fn longest(x: &str, y: &str) -> &str {

if x.len() > y.len() { x } else { y }

}示例 10-20:一个 longest 函数的实现,它返回两个字符串 slice 中较长者,现在还不能编译

相应地会出现如下有关生命周期的错误:

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10> cargo new example10_3_3

Creating binary (application) `example10_3_3` package

note: see more `Cargo.toml` keys and their definitions at https://doc.rust-lang.org/cargo/reference/manifest.html

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10> cd example10_3_3

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10\example10_3_3> cargo run

Compiling example10_3_3 v0.1.0 (F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10\example10_3_3)

error[E0106]: missing lifetime specifier

--> src\main.rs:9:33

|

9 | fn longest(x: &str, y: &str) -> &str {

| ---- ---- ^ expected named lifetime parameter

|

= help: this function's return type contains a borrowed value, but the signature does not say whether it is borrowed from `x` or `y`

help: consider introducing a named lifetime parameter

|

9 | fn longest<'a>(x: &'a str, y: &'a str) -> &'a str {

| ++++ ++ ++ ++

For more information about this error, try `rustc --explain E0106`.

error: could not compile `example10_3_3` (bin "example10_3_3") due to 1 previous error

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10\example10_3_3>

提示文本揭示了返回值需要一个泛型生命周期参数,因为 Rust 并不知道将要返回的引用是指向 x 或 y。事实上我们也不知道,因为函数体中 if 块返回一个 x 的引用而 else 块返回一个 y 的引用!

当我们定义这个函数的时候,并不知道传递给函数的具体值,所以也不知道到底是 if 还是 else 会被执行。我们也不知道传入的引用的具体生命周期,所以也就不能像示例 10-17 和 10-18 那样通过观察作用域来确定返回的引用是否总是有效。借用检查器自身同样也无法确定,因为它不知道 x 和 y 的生命周期是如何与返回值的生命周期相关联的。为了修复这个错误,我们将增加泛型生命周期参数来定义引用间的关系以便借用检查器可以进行分析。

生命周期注解语法

生命周期注解并不改变任何引用的生命周期的长短。相反它们描述了多个引用生命周期相互的关系,而不影响其生命周期。与当函数签名中指定了泛型类型参数后就可以接受任何类型一样,当指定了泛型生命周期后函数也能接受任何生命周期的引用。

生命周期注解有着一个不太常见的语法:生命周期参数名称必须以撇号(')开头,其名称通常全是小写,类似于泛型其名称非常短。大多数人使用 'a 作为第一个生命周期注解。生命周期参数注解位于引用的 & 之后,并有一个空格来将引用类型与生命周期注解分隔开。

这里有一些例子:我们有一个没有生命周期参数的 i32 的引用,一个有叫做 'a 的生命周期参数的 i32 的引用,和一个生命周期也是 'a 的 i32 的可变引用:

&i32 // 引用

&'a i32 // 带有显式生命周期的引用

&'a mut i32 // 带有显式生命周期的可变引用单个的生命周期注解本身没有多少意义,因为生命周期注解告诉 Rust 多个引用的泛型生命周期参数如何相互联系的。让我们在 longest 函数的上下文中理解生命周期注解如何相互联系。

函数签名中的生命周期注解

为了在函数签名中使用生命周期注解,需要在函数名和参数列表间的尖括号中声明泛型生命周期(lifetime)参数,就像泛型类型(type)参数一样。

我们希望函数签名表达如下限制:也就是这两个参数和返回的引用存活的一样久。(两个)参数和返回的引用的生命周期是相关的。就像示例 10-21 中在每个引用中都加上了 'a 那样。

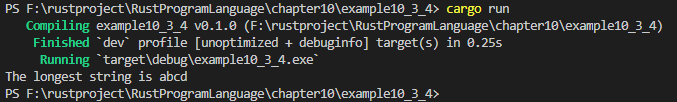

文件名:src/main.rs

// 10.3节 函数签名中的生命周期注解 参考:示例 10-21:longest 函数定义指定了签名中所有的引用必须有相同的生命周期 'a

fn main() {

let string1 = String::from("abcd");

let string2 = "xyz";

let result = longest(string1.as_str(), string2);

println!("The longest string is {result}");

}

//数签名中的生命周期注解

fn longest<'a>(x: &'a str, y: &'a str) -> &'a str {

if x.len() > y.len() { x } else { y }

}编译运行:

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10> cargo new example10_3_4

Creating binary (application) `example10_3_4` package

note: see more `Cargo.toml` keys and their definitions at https://doc.rust-lang.org/cargo/reference/manifest.html

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10> cd example10_3_4

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10\example10_3_4> cargo run

Compiling example10_3_4 v0.1.0 (F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10\example10_3_4)

Finished `dev` profile [unoptimized + debuginfo] target(s) in 0.25s

Running `target\debug\example10_3_4.exe`

The longest string is abcd

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10\example10_3_4>

这段代码能够编译并会产生我们希望得到的示例 10-19 中的 main 函数的结果。

现在函数签名表明对于某些生命周期 'a,函数会获取两个参数,它们都是与生命周期 'a 存在的至少一样长的字符串 slice。函数会返回一个同样也与生命周期 'a 存在的至少一样长的字符串 slice。它的实际含义是 longest 函数返回的引用的生命周期与函数参数所引用的值的生命周期的较小者一致。这些关系就是我们希望 Rust 分析代码时所使用的。

记住通过在函数签名中指定生命周期参数时,我们并没有改变任何传入值或返回值的生命周期,而是指出任何不满足这个约束条件的值都将被借用检查器拒绝。注意 longest 函数并不需要知道 x 和 y 具体会存在多久,而只需要知道有某个可以被 'a 替代的作用域将会满足这个签名。

当在函数中使用生命周期注解时,这些注解出现在函数签名中,而不存在于函数体中的任何代码中。生命周期注解成为了函数约定的一部分,非常像签名中的类型。让函数签名包含生命周期约定意味着 Rust 编译器的工作变得更简单了。如果函数注解有误或者调用方法不对,编译器错误可以更准确地指出代码和限制的部分。如果不这么做的话,Rust 编译会对我们期望的生命周期关系做更多的推断,这样编译器可能只能指出离出问题地方很多步之外的代码。

当具体的引用被传递给 longest 时,被 'a 所替代的具体生命周期是 x 的作用域与 y 的作用域相重叠的那一部分。换一种说法就是泛型生命周期 'a 的具体生命周期等同于 x 和 y 的生命周期中较小的那一个。因为我们用相同的生命周期参数 'a 标注了返回的引用值,所以返回的引用值就能保证在 x 和 y 中较短的那个生命周期结束之前保持有效。

让我们看看如何通过传递拥有不同具体生命周期的引用来限制 longest 函数的使用。示例 10-22 是一个很直观的例子。

文件名:src/main.rs

// 10.3节 函数签名中的生命周期注解 参考:示例 10-22: 通过拥有不同的具体生命周期的 String 值调用 longest 函数

fn main() {

let string1 = String::from("long string is long");

{

let string2 = String::from("xyz");

let result = longest(string1.as_str(), string2.as_str());

println!("The longest string is {result}");

}

}

//数签名中的生命周期注解

fn longest<'a>(x: &'a str, y: &'a str) -> &'a str {

if x.len() > y.len() {x} else {y}

}编译运行:

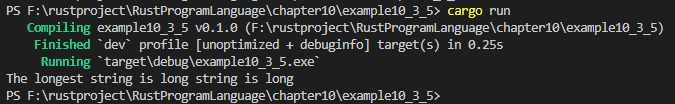

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10> cargo new example10_3_5

Creating binary (application) `example10_3_5` package

note: see more `Cargo.toml` keys and their definitions at https://doc.rust-lang.org/cargo/reference/manifest.html

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10> cd example10_3_5

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10\example10_3_5> cargo run

Compiling example10_3_5 v0.1.0 (F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10\example10_3_5)

Finished `dev` profile [unoptimized + debuginfo] target(s) in 0.25s

Running `target\debug\example10_3_5.exe`

The longest string is long string is long

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10\example10_3_5>

在这个例子中,string1 直到外部作用域结束都是有效的,string2 则在内部作用域中是有效的,而 result 则引用了一些直到内部作用域结束都是有效的值。借用检查器认可这些代码;它能够编译和运行,并打印出 The longest string is long string is long。

接下来,让我们尝试另外一个例子,该例子揭示了 result 的引用的生命周期必须是两个参数中较短的那个。以下代码将 result 变量的声明移动出内部作用域,但是将 result 和 string2 变量的赋值语句一同留在内部作用域中。接着,使用了变量 result 的 println! 也被移动到内部作用域之外。注意示例 10-23 中的代码不能通过编译:

文件名:src/main.rs

// 10.3节 函数签名中的生命周期注解 参考:示例 10-23:尝试在 string2 离开作用域之后使用 result

fn main() {

let string1 = String::from("long string is long");

let result;

{

let string2 = String::from("xyz");

result = longest(string1.as_str(), string2.as_str());

}

println!("The longest string is {result}");

}

//数签名中的生命周期注解

fn longest<'a>(x: &'a str, y: &'a str) -> &'a str{

if x.len() > y.len() {x} else {y}

}示例 10-23:尝试在 string2 离开作用域之后使用 result

如果尝试编译这段代码会出现如下错误:

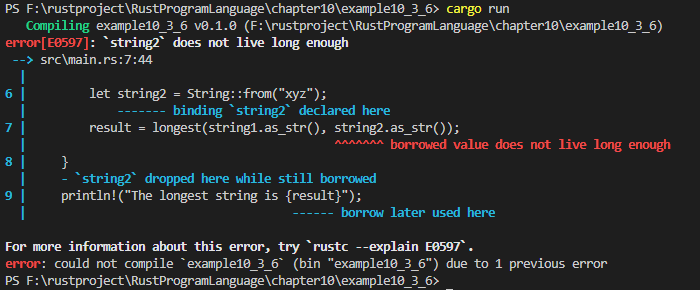

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10> cargo new example10_3_6

Creating binary (application) `example10_3_6` package

note: see more `Cargo.toml` keys and their definitions at https://doc.rust-lang.org/cargo/reference/manifest.html

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10> cd example10_3_6

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10\example10_3_6> cargo run

Compiling example10_3_6 v0.1.0 (F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10\example10_3_6)

error[E0597]: `string2` does not live long enough

--> src\main.rs:7:44

|

6 | let string2 = String::from("xyz");

| ------- binding `string2` declared here

7 | result = longest(string1.as_str(), string2.as_str());

| ^^^^^^^ borrowed value does not live long enough

8 | }

| - `string2` dropped here while still borrowed

9 | println!("The longest string is {result}");

| ------ borrow later used here

For more information about this error, try `rustc --explain E0597`.

error: could not compile `example10_3_6` (bin "example10_3_6") due to 1 previous error

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10\example10_3_6>

错误表明为了保证 println! 中的 result 是有效的,string2 需要直到外部作用域结束都是有效的。Rust 知道这些是因为(longest)函数的参数和返回值都使用了相同的生命周期参数 'a。

作为人类,我们可以直观地发现 string1 比 string2 更长,因此 result 会包含指向 string1 的引用。因为 string1 尚未离开作用域,对于 println! 来说 string1 的引用仍然是有效的。然而,编译器并不能识别出这种情况。我们通过生命周期参数告诉 Rust 的是: longest 函数返回的引用的生命周期应该与传入参数的生命周期中较短那个保持一致。因此,借用检查器不允许示例 10-23 中的代码,因为它可能会存在无效的引用。

请尝试更多采用不同的值和不同生命周期的引用作为 longest 函数的参数和返回值的实验。并在开始编译前猜想你的实验能否通过借用检查器,接着编译一下看看你的理解是否正确!

深入理解生命周期

指定生命周期参数的正确方式依赖函数实现的具体功能。例如,如果将 longest 函数的实现修改为总是返回第一个参数而不是最长的字符串 slice,就不需要为参数 y 指定一个生命周期。如下代码将能够编译:

文件名:src/main.rs

fn longest<'a>(x: &'a str, y: &str) -> &'a str {

x

}我们为参数 x 和返回值指定了生命周期参数 'a,不过没有为参数 y 指定,因为 y 的生命周期与参数 x 和返回值的生命周期没有任何关系。

当从函数返回一个引用,返回值的生命周期参数需要与一个参数的生命周期参数相匹配。如果返回的引用没有指向任何一个参数,那么唯一的可能就是它指向一个函数内部创建的值。然而它将会是一个悬垂引用,因为它将会在函数结束时离开作用域。尝试考虑这个并不能编译的 longest 函数实现:

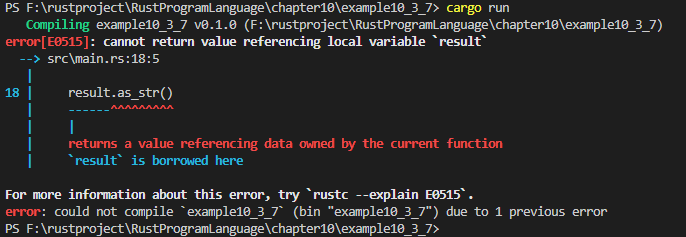

文件名:src/main.rs

fn longest<'a>(x: &str, y: &str) -> &'a str {

let result = String::from("really long string");

result.as_str()

}即便我们为返回值指定了生命周期参数 'a,这个实现却编译失败了,因为返回值的生命周期与参数完全没有关联。这里是会出现的错误信息:

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10\example10_3_7> cargo run

Compiling example10_3_7 v0.1.0 (F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10\example10_3_7)

error[E0515]: cannot return value referencing local variable `result`

--> src\main.rs:18:5

|

18 | result.as_str()

| ------^^^^^^^^^

| |

| returns a value referencing data owned by the current function

| `result` is borrowed here

For more information about this error, try `rustc --explain E0515`.

error: could not compile `example10_3_7` (bin "example10_3_7") due to 1 previous error

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10\example10_3_7>

出现的问题是 result 在 longest 函数的结尾将离开作用域并被清理,而我们尝试从函数返回一个 result 的引用。无法指定生命周期参数来改变悬垂引用,而且 Rust 也不允许我们创建一个悬垂引用。在这种情况,最好的解决方案是返回一个有所有权的数据类型而不是一个引用,这样函数调用者就需要负责清理这个值了。

综上,生命周期语法是用于将函数的多个参数与其返回值的生命周期进行关联的。一旦它们形成了某种关联,Rust 就有了足够的信息来允许内存安全的操作并阻止会产生悬垂指针亦或是违反内存安全的行为。

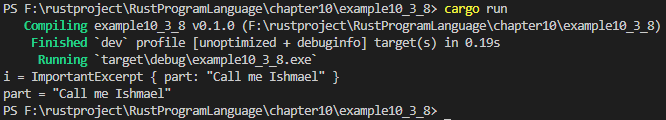

结构体定义中的生命周期注解

目前为止,我们定义的结构体全都包含拥有所有权的类型。也可以定义包含引用的结构体,不过这需要为结构体定义中的每一个引用添加生命周期注解。示例 10-24 中有一个存放了一个字符串 slice 的结构体 ImportantExcerpt。

文件名:src/main.rs

// 10.3节 结构体定义中的生命周期注解 参考 示例 10-24:一个存放引用的结构体,所以其定义需要生命周期注解

#[derive(Debug)]

struct ImportantExcerpt<'a> {

part: &'a str,

}

fn main() {

let novel = String::from("Call me Ishmael. Some years ago...");

let first_sentence = novel.split('.').next().unwrap();

let i = ImportantExcerpt {

part:first_sentence,

};

println!("i = {:?}", i);

println!("part = {:?}", i.part);

}编译运行:

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10> cargo new example10_3_8

note: see more `Cargo.toml` keys and their definitions at https://doc.rust-lang.org/cargo/reference/manifest.html

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10> cd example10_3_8

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10\example10_3_8> cargo run

Compiling example10_3_8 v0.1.0 (F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10\example10_3_8)

Finished `dev` profile [unoptimized + debuginfo] target(s) in 0.19s

Running `target\debug\example10_3_8.exe`

i = ImportantExcerpt { part: "Call me Ishmael" }

part = "Call me Ishmael"

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10\example10_3_8>

这个结构体只有一个字段 part,它存放了一个字符串 slice,这是一个引用。类似于泛型参数类型,必须在结构体名称后面的尖括号中声明泛型生命周期参数,以便在结构体定义中使用生命周期参数。这个注解意味着 ImportantExcerpt 的实例不能比其 part 字段中的引用存在的更久。

这里的 main 函数创建了一个 ImportantExcerpt 的实例,它存放了变量 novel 所拥有的 String 的第一个句子的引用。novel 的数据在 ImportantExcerpt 实例创建之前就存在。另外,直到 ImportantExcerpt 离开作用域之后 novel 都不会离开作用域,所以 ImportantExcerpt 实例中的引用是有效的。

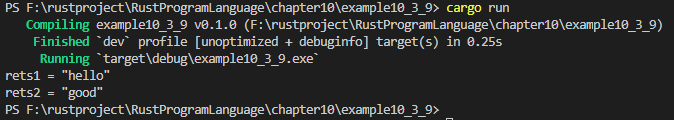

生命周期省略(Lifetime Elision)

现在我们已经知道了每一个引用都有一个生命周期,而且我们需要为那些使用了引用的函数或结构体指定生命周期。然而,第四章的示例 4-9 中有一个函数,再次展示为如示例 10-25 所示,它没有生命周期注解却能编译成功:

文件名:src/lib.rs

// 10.3节 生命周期省略(Lifetime Elision) 参考 示例 10-25:示例 4-9 定义了一个没有使用生命周期注解的函数,即便其参数和返回值都是引用

fn main() {

let s1 = String::from("hello world");

let s2 = String::from("good book");

let rets1 = first_word(&s1);

println!("rets1 = {:?}", rets1);

let rets2 = first_word2(&s2);

println!("rets2 = {:?}", rets2);

}

//没有标记生命周期

fn first_word(s:&str) -> &str {

let bytes = s.as_bytes();

for (i, &item) in bytes.iter().enumerate() {

if item == b' ' {

return &s[0..i];

}

}

&s[..]

}

//标记生命周期

fn first_word2<'a>(s: &'a str) -> &'a str {

let bytes = s.as_bytes();

for (i, &item) in bytes.iter().enumerate() {

if item == b' ' {

return &s[0..i];

}

}

&s[..]

}

编译运行

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10> cargo new example10_3_9

Creating binary (application) `example10_3_9` package

note: see more `Cargo.toml` keys and their definitions at https://doc.rust-lang.org/cargo/reference/manifest.html

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10> cd example10_3_9

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10\example10_3_9> cargo run

Compiling example10_3_9 v0.1.0 (F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10\example10_3_9)

Finished `dev` profile [unoptimized + debuginfo] target(s) in 0.25s

Running `target\debug\example10_3_9.exe`

rets1 = "hello"

rets2 = "good"

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10\example10_3_9>

这个函数没有生命周期注解却能编译是由于一些历史原因:在早期版本(pre-1.0)的 Rust 中,这的确是不能编译的。每一个引用都必须有明确的生命周期。那时的函数签名将会写成这样:

fn first_word<'a>(s: &'a str) -> &'a str {在编写了很多 Rust 代码后,Rust 团队发现在特定情况下 Rust 程序员们总是重复地编写一模一样的生命周期注解。这些场景是可预测的并且遵循几个明确的模式。接着 Rust 团队就把这些模式编码进了 Rust 编译器中,如此借用检查器在这些情况下就能推断出生命周期而不再强制程序员显式的增加注解。

这里我们提到一些 Rust 的历史是因为更多的明确的模式被合并和添加到编译器中是完全可能的。未来可能只需要更少的生命周期注解。

被编码进 Rust 引用分析的模式被称为 生命周期省略规则(lifetime elision rules)。这并不是需要程序员遵守的规则;这些规则是一系列特定的场景,此时编译器会考虑,如果代码符合这些场景,就无需明确指定生命周期。

省略规则并不提供完整的推断。如果 Rust 在明确遵守这些规则的前提下变量的生命周期仍然是模棱两可的话,它不会猜测剩余引用的生命周期应该是什么。编译器会在可以通过增加生命周期注解来解决错误问题的地方给出一个错误提示,而不是进行推断或猜测。

函数或方法的参数的生命周期被称为 输入生命周期(input lifetimes),而返回值的生命周期被称为 输出生命周期(output lifetimes)。

编译器采用三条规则来判断引用何时不需要明确的注解。第一条规则适用于输入生命周期,后两条规则适用于输出生命周期。如果编译器检查完这三条规则后仍然存在没有计算出生命周期的引用,编译器将会停止并生成错误。这些规则适用于 fn 定义,以及 impl 块。

第一条规则是编译器为每一个引用参数都分配一个生命周期参数。换句话说就是,函数有一个引用参数的就有一个生命周期参数:fn foo<'a>(x: &'a i32),有两个引用参数的函数就有两个不同的生命周期参数,fn foo<'a, 'b>(x: &'a i32, y: &'b i32),依此类推。

第二条规则是如果只有一个输入生命周期参数,那么将它赋予给所有输出生命周期参数:fn foo<'a>(x: &'a i32) -> &'a i32。

第三条规则是如果方法有多个输入生命周期参数并且其中一个参数是 &self 或 &mut self,说明这是个方法,那么所有输出生命周期参数被赋予 self 的生命周期。第三条规则使得方法更容易读写,因为只需更少的符号。

假设我们自己就是编译器。并应用这些规则来计算示例 10-25 中 first_word 函数签名中的引用的生命周期。开始时签名中的引用并没有关联任何生命周期:

fn first_word(s: &str) -> &str {接着编译器应用第一条规则,也就是每个引用参数都有其自己的生命周期。我们像往常一样称之为 'a,所以现在签名看起来像这样:

fn first_word<'a>(s: &'a str) -> &str {对于第二条规则,因为这里正好只有一个输入生命周期参数所以是适用的。第二条规则表明输入参数的生命周期将被赋予输出生命周期参数,所以现在签名看起来像这样:

fn first_word<'a>(s: &'a str) -> &'a str {现在这个函数签名中的所有引用都有了生命周期,如此编译器可以继续它的分析而无须程序员标记这个函数签名中的生命周期。

让我们再看看另一个例子,这次我们从示例 10-20 中没有生命周期参数的 longest 函数开始:

fn longest(x: &str, y: &str) -> &str {再次假设我们自己就是编译器并应用第一条规则:每个引用参数都有其自己的生命周期。这次有两个参数,所以就有两个(不同的)生命周期:

fn longest<'a, 'b>(x: &'a str, y: &'b str) -> &str {再来应用第二条规则,因为函数存在多个输入生命周期,它并不适用于这种情况。再来看第三条规则,它同样也不适用,这是因为没有 self 参数。应用了三个规则之后编译器还没有计算出返回值类型的生命周期。这就是在编译示例 10-20 的代码时会出现错误的原因:编译器使用所有已知的生命周期省略规则,仍不能计算出签名中所有引用的生命周期。

因为第三条规则真正能够适用的就只有方法签名,现在就让我们看看那种情况中的生命周期,并看看为什么这条规则意味着我们经常不需要在方法签名中标注生命周期。

方法定义中的生命周期注解

当为带有生命周期的结构体实现方法时,其语法依然类似示例 10-11 中展示的泛型类型参数的语法。我们在哪里声明和使用生命周期参数,取决于它们是与结构体字段相关还是与方法参数和返回值相关。

(实现方法时)结构体字段的生命周期必须总是在 impl 关键字之后声明并在结构体名称之后被使用,因为这些生命周期是结构体类型的一部分。

impl 块里的方法签名中,引用可能与结构体字段中的引用相关联,也可能是独立的。另外,生命周期省略规则也经常让我们无需在方法签名中使用生命周期注解。让我们看看一些使用示例 10-24 中定义的结构体 ImportantExcerpt 的例子。

首先,这里有一个方法 level。其唯一的参数是 self 的引用,而且返回值只是一个 i32,并不引用任何值:

impl<'a> ImportantExcerpt<'a> {

fn level(&self) -> i32 {

3

}

}impl 之后和类型名称之后的生命周期参数是必要的,不过因为第一条生命周期规则我们并不必须标注 self 引用的生命周期。

这里是一个适用于第三条生命周期省略规则的例子:

impl<'a> ImportantExcerpt<'a> {

fn announce_and_return_part(&self, announcement: &str) -> &str {

println!("Attention please: {announcement}");

self.part

}

}这里有两个输入生命周期,所以 Rust 应用第一条生命周期省略规则并给予 &self 和 announcement 它们各自的生命周期。接着,因为其中一个参数是 &self,返回值类型被赋予了 &self 的生命周期,这样所有的生命周期都被计算出来了。

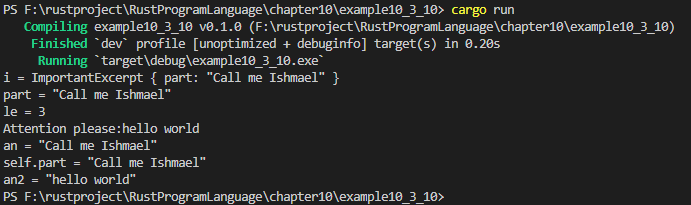

完整的实验代码:

// 10.3节 方法定义中的生命周期注解

#[derive(Debug)]

struct ImportantExcerpt<'a> {

part: &'a str,

}

impl<'a> ImportantExcerpt<'a> {

fn level(&self) -> i32 {

3

}

}

//这里是一个适用于第三条生命周期省略规则的例子:

impl<'a> ImportantExcerpt<'a> {

fn announce_and_return_part(&self, announcement: &str) -> &str {

println!("Attention please:{announcement}");

self.part

}

}

//返回是传进来的参数,这样必须添加生命周期注解

impl<'a> ImportantExcerpt<'a> {

fn announce_and_return_announcement<'b>(&self, announcement: &'b str) -> &'b str {

println!("self.part = {:?}", self.part);

announcement //返回传进来的参数

}

}

fn main() {

let novel = String::from("Call me Ishmael. Some years ago...");

let first_sentence = novel.split('.').next().unwrap();

let i = ImportantExcerpt {

part:first_sentence,

};

println!("i = {:?}", i);

println!("part = {:?}", i.part);

let le = i.level();

println!("le = {:?}", le);

let s2 = "hello world";

let an = i.announce_and_return_part(s2);

println!("an = {:?}", an);

let an2 = i.announce_and_return_announcement(s2);

println!("an2 = {:?}", an2);

}编译运行:

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10\example10_3_10> cargo run

Compiling example10_3_10 v0.1.0 (F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10\example10_3_10)

Finished `dev` profile [unoptimized + debuginfo] target(s) in 0.20s

Running `target\debug\example10_3_10.exe`

i = ImportantExcerpt { part: "Call me Ishmael" }

part = "Call me Ishmael"

le = 3

Attention please:hello world

an = "Call me Ishmael"

self.part = "Call me Ishmael"

an2 = "hello world"

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10\example10_3_10>

静态生命周期

这里有一种特殊的生命周期值得讨论:'static,其生命周期能够存活于整个程序期间。所有的字符串字面值都拥有 'static 生命周期,我们也可以选择像下面这样标注出来:

// 10.3节 静态生命周期

fn main() {

let aa = 50;

let s1: &str;

{

let s: &'static str = "I have a static lifetime.";

s1 = &s;

} //s是静态生命周期,所以离开作用域还是可以访问的

println!("aa = {}", aa);

println!("s1 = {}", s1);

}编译运行:

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10\example10_3_11> cargo run

Compiling example10_3_11 v0.1.0 (F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10\example10_3_11)

Finished `dev` profile [unoptimized + debuginfo] target(s) in 0.18s

Running `target\debug\example10_3_11.exe`

aa = 50

s1 = I have a static lifetime.

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10\example10_3_11>

这个字符串的文本被直接储存在程序的二进制文件中而这个文件总是可用的。因此所有的字符串字面值都是 'static 的。

你可能在错误信息的帮助文本中见过使用 'static 生命周期的建议,不过将引用指定为 'static 之前,思考一下这个引用是否真的在整个程序的生命周期里都有效,以及你是否希望它存在得这么久。大部分情况中,推荐 'static 生命周期的错误信息都是尝试创建一个悬垂引用或者可用的生命周期不匹配的结果。在这种情况下的解决方案是修复这些问题而不是指定一个 'static 的生命周期。

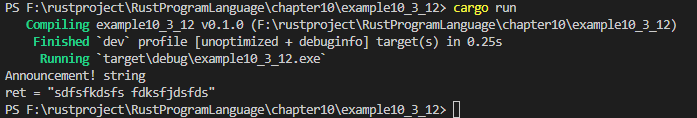

结合泛型类型参数、trait bounds和生命周期

让我们简要的看一下在同一函数中指定泛型类型参数、trait bounds 和生命周期的语法!

// 10.3节 结合泛型类型参数、trait bounds和生命周期

use std::fmt::Display;

fn longest_width_an_announcement<'a, T> (

x: &'a str,

y: &'a str,

ann: T,

) -> &'a str

where

T: Display,

{

println!("Announcement! {ann}");

if x.len() > y.len() {x} else {y}

}

fn main() {

let s1 = String::from("sdfsfkdsfs fdksfjdsfds");

let s2 = String::from("hello");

let ret = longest_width_an_announcement(&s1, &s2, "string");

println!("ret = {:?}", ret);

}

编译运行:

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10> cargo new example10_3_12

Creating binary (application) `example10_3_12` package

note: see more `Cargo.toml` keys and their definitions at https://doc.rust-lang.org/cargo/reference/manifest.html

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10> cd example10_3_12

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10\example10_3_12> cargo run

Compiling example10_3_12 v0.1.0 (F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10\example10_3_12)

Finished `dev` profile [unoptimized + debuginfo] target(s) in 0.25s

Running `target\debug\example10_3_12.exe`

Announcement! string

ret = "sdfsfkdsfs fdksfjdsfds"

PS F:\rustproject\RustProgramLanguage\chapter10\example10_3_12>

这个是示例 10-21 中那个返回两个字符串 slice 中较长者的 longest 函数,不过带有一个额外的参数 ann。ann 的类型是泛型 T,它可以被放入任何实现了 where 从句中指定的 Display trait 的类型。这个额外的参数会使用 {} 打印,这也就是为什么 Display trait bound 是必须的。因为生命周期也是泛型,所以生命周期参数 'a 和泛型类型参数 T 都位于函数名后的同一尖括号列表中。

总结

这一章介绍了很多的内容!现在你知道了泛型类型参数、trait 和 trait bounds 以及泛型生命周期类型,你已经准备好编写既不重复又能适用于多种场景的代码了。泛型类型参数意味着代码可以适用于不同的类型。trait 和 trait bounds 保证了即使类型是泛型的,这些类型也会拥有所需要的行为。由生命周期注解所指定的引用生命周期之间的关系保证了这些灵活多变的代码不会出现悬垂引用。而所有的这一切发生在编译时所以不会影响运行时效率!

你可能不会相信,这个话题还有更多需要学习的内容:第十八章会讨论 trait 对象,这是另一种使用 trait 的方式。还有更多更复杂的涉及生命周期注解的场景,只有在非常高级的情况下才会需要它们;对于这些内容,请阅读 Rust Reference。不过接下来,让我们聊聊如何在 Rust 中编写测试,来确保代码的所有功能能像我们希望的那样工作!

更多推荐

已为社区贡献7条内容

已为社区贡献7条内容

所有评论(0)