MCP保姆级详解和实战案例(附完整代码)

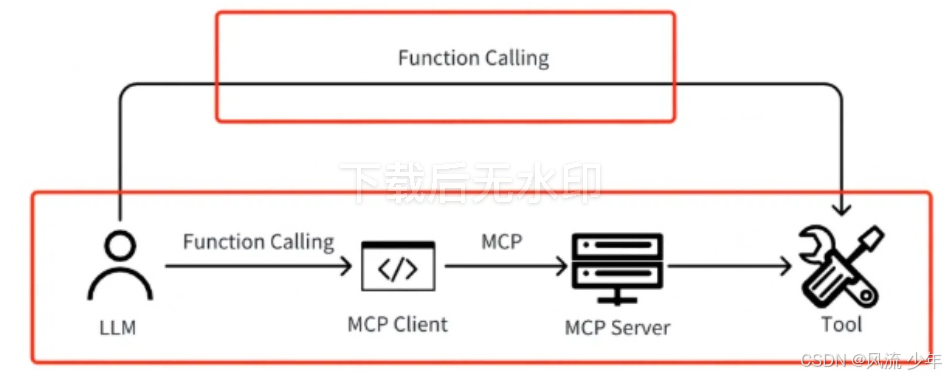

Function Call是大模型基于意图识别触发预设函数的机制,其本质是模型与外部工具的“点对点”交互。平台依赖性强:对于不同大模型(如GPT、Claude),Function Call的实现差异显著,开发者需要为每个大模型编写适配的相关代码。扩展性不足:新增工具需调整模型接口或重新训练,难以支持复杂多轮任务。从模型调用工具的流程来看,MCP 跟 Function Call 是调用链上的两个环节

一:简介

MCP(Model Context Protocol,模型上下文协议)是由Anthropic公司推出的开放标准协议,旨在为大语言模型LLM(Large Language Model)与外部数据源、工具及服务提供统一的交互接口规范。

MCP 的主要目的在于解决当前 AI 模型因数据孤岛限制而无法充分发挥潜力的难题,使得 AI 应用能够安全地访问和操作本地及远程数据,为 AI 应用提供了连接万物的接口。

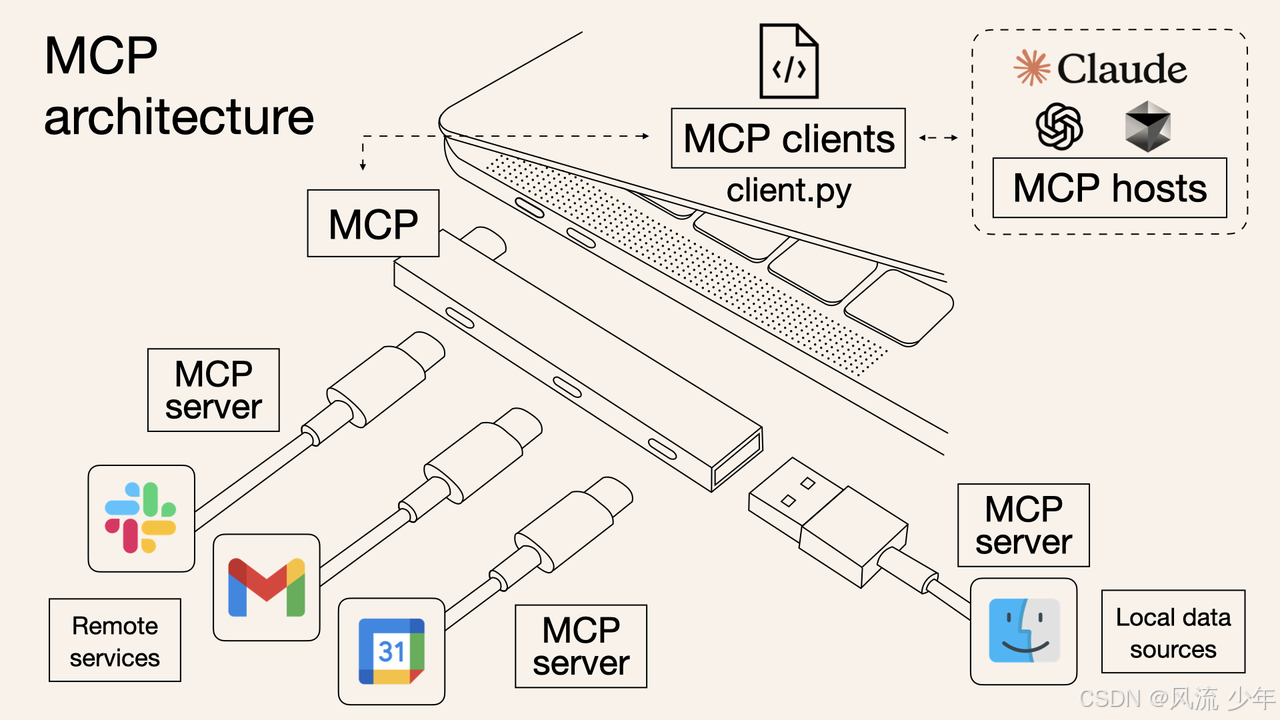

1.1 MCP架构

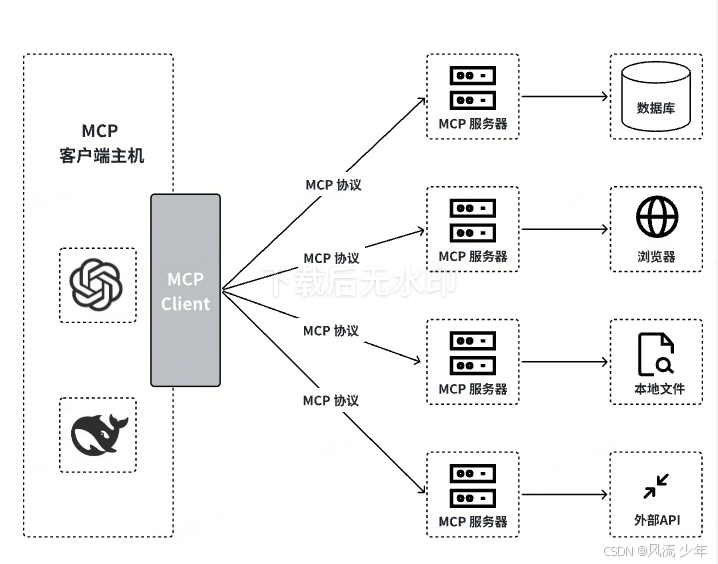

- MCP主机(host):如Claude Desktop、IDE等AI工具,负责发起请求。

- MCP客户端(client):与服务器一对一连接,管理协议通信。

- MCP服务器(server):轻量级程序,通过标准化协议安全访问本地或远程资源(如数据库、API、文件系统)。 MCP 原语包括:

- 资源(Resources):公开数据(如文件、数据库记录),支持文本和二进制格式。

- 提示(Prompts):定义可复用的交互模板,驱动工作流。

- 工具(Tools):提供可执行功能(如 API 调用、计算),由模型控制。

- 采样(Sampling):服务器通过客户端请求 LLM 推理,保持安全隔离。

- 根(Roots):定义服务器操作范围(如文件路径、API 端点)。

可以将 MCP 视为 AI 应用的 USB-C 端口。正如 USB-C 提供了一种将设备连接到各种外围设备和配件的标准化方式一样,MCP 提供了一种将 AI 模型连接到不同数据源和工具的标准化方式。

MCP hosts --> client.py --> MCP --> MCP Server --> 数据库、API、文件、浏览器

MCP Server 的官方描述:

一个轻量级程序,每个程序都通过标准化模型上下文协议公开特定功能。简单理解,就是通过标准化协议与客户端交互,让模型调用特定的数据源或工具功能。常见的 MCP Server 有:

- 文件和数据访问类:让大模型能够操作、访问本地文件或数据库,如 File System MCP Server。

- Web 自动化类:让大模型能够操作浏览器,如 Pupteer MCP Server。

- 三方工具集成类:让大模型能够调用三方平台暴露的 API,如 高德地图 MCP Server。

MCP Server 的获取途径:

- 官方收集和分享的MCP Server: https://github.com/modelcontextprotocol/servers

- mcp.so

- MCP市场 - 国内最全MCP Servers收录平台 https://mcpmarket.cn/

- ModelScope - MCP 广场 https://modelscope.cn/mcp

1.2 MCP特点

标准化接口:MCP定义统一的通信协议,开发者仅需按规范实现MCP Server(如天气查询服务,行程规划服务,数据库查询服务等等),即可被任何支持MCP的Host(如Claude Desktop、Cursor)调用,无需关注底层模型差异。

- 分层处理能力:MCP将工具调用拆分为资源、工具、提示词三层,支持复杂任务的上下文传递与多步推理。例如:通过MCP Server访问GitHub API时,模型可动态解析代码库结构并生成操作指令,而无需硬编码适配逻辑。

- 生态开放性:MCP的开放协议吸引了大量社区贡献的现成插件(如Git、Slack、AWS服务),开发者可直接复用,显著降低开发门槛。

1.3 Function Call简介

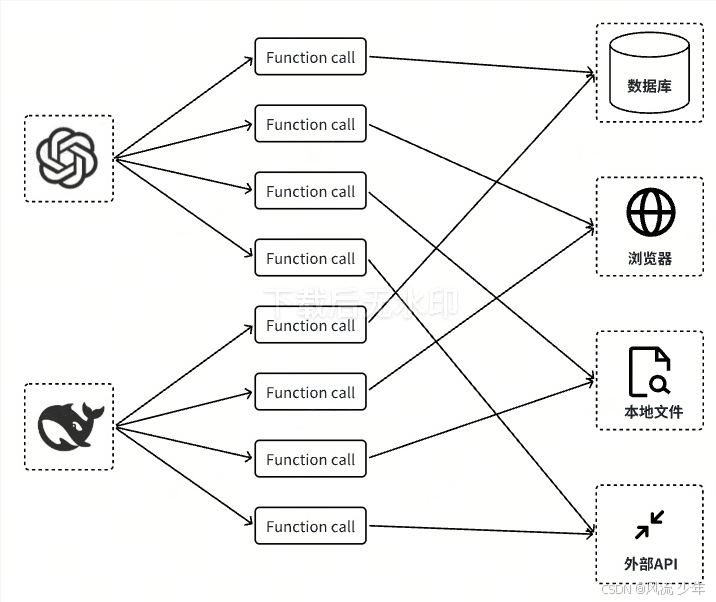

Function Call是大模型基于意图识别触发预设函数的机制,其本质是模型与外部工具的“点对点”交互。然而其存在两大核心局限性:

- 平台依赖性强:对于不同大模型(如GPT、Claude),Function Call的实现差异显著,开发者需要为每个大模型编写适配的相关代码。

- 扩展性不足:新增工具需调整模型接口或重新训练,难以支持复杂多轮任务。

-

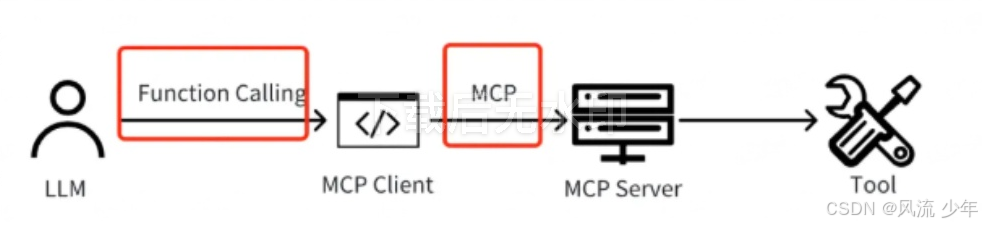

从模型调用工具的流程来看,MCP 跟 Function Call 是调用链上的两个环节。

- MCP 是指协议本身(Client 和 Server 的连接),MCP 协议只关心调用 Tool 时的通信方式。

- Function Call 是模型调用工具的主流手段之一(纯靠系统提示词也可以),关心的是模型怎么用这些工具

-

从agent(模型+工具)整体来看,MCP 是对 Function Call 的封装

- MCP 此时指的是整个让模型调用工具的整体手段(即图中下面这个红框)

- Function Call 是指 Host 里的 LLM 向 MCP Client 调用工具的手段

1.4 MCP 对比 Function Call

| 对比维度 | Function Call | MCP |

|---|---|---|

| 协议标准 | 私有协议(各个大模型自定规则) | 开放协议(JSON-RPC 2.0) |

| 工具发现 | 动态获取(initialize请求) | 静态预定义 |

| 调用方式 | 同进程函数 或 API | STDIO / SSE / 同进程 |

| 扩展成本 | 高(新增工具需重新调试模型) | 低(工具热插拔,模型无需改动) |

| 适用场景 | 简单任务(单次函数调用) | 复杂流程(多工具协同 + 数据交互) |

| 生态协作 | 工具与大模型强绑定 | 工具开发者与 Agent 开发者解耦 |

1.5 MCP与RAG

1.5.1 MCP直连数据库的范式革新

MCP最革命性的应用场景之一是大模型与数据库的直接交互。传统RAG(检索增强生成)依赖向量检索技术,存在检索精度低、文档切片局部性强、多轮推理能力弱等缺陷。而MCP通过以下方式实现更高效的数据访问:

- 结构化查询能力:

MCP Server可暴露数据库Schema并支持自然语言转SQL(Text-to-SQL)。例如,用户提问“商品表中价格最高的车型是什么?”时,MCP自动生成并执行SQL查询,返回结构化结果供模型生成自然语言响应。相较于RAG的模糊匹配,这种基于Schema的精准查询显著提升答案可靠性。 - 动态上下文管理:

MCP支持跨会话的上下文传递。例如,在数据分析场景中,模型可先通过MCP获取数据库表结构,再根据用户后续提问动态调整查询策略(如关联多表、聚合统计),而RAG因缺乏全局视图难以实现此类复杂操作。 - 安全与效率平衡:

MCP默认提供只读接口,并支持本地化部署。开发者可通过权限控制(如仅开放特定表或视图)避免敏感数据泄露,同时减少因全量数据上传导致的延迟与成本。

1.5.2 MCP能否替代传统RAG?

尽管MCP在结构化数据场景中展现优势,但RAG在以下场景仍不可替代:

- 非结构化文本处理:RAG擅长从海量文档(如PDF、网页)中提取片段信息,而MCP更适用于数据库、API等结构化资源;

- 低成本长文本处理:直接向大模型输入超长文本(如千万字级)会导致响应延迟与成本激增,而RAG通过精准检索切片可大幅降低开销;

- 动态知识更新:RAG可通过实时更新向量库快速纳入新知识,而MCP需依赖后端系统(如数据库)的数据更新机制。

1.5.3 未来趋势

MCP与RAG可能走向协同。例如,MCP可调用RAG服务作为其“知识检索工具”,或通过智能体架构将两者整合:MCP处理结构化查询,RAG补充非结构化知识,形成互补的混合增强方案。

MCP通过协议标准化重新定义了AI与外部系统的交互范式,其直连数据库的能力为结构化数据场景提供了更高效、精准的解决方案。然而,技术演进的终局并非“替代”,而是生态融合——MCP与RAG、Agent等技术的协同,将共同推动大模型从“封闭的知识库”进化为“开放的智能体”。

二:第三方MCP服务(百度地图API)

想要使用 MCP 技术,首先需要找到一个支持 MCP 协议的客户端,然后就是找到符合我们需求的 MCP 服务器,然后在 MCP 客户端里调用这些服务。

2.1 准备

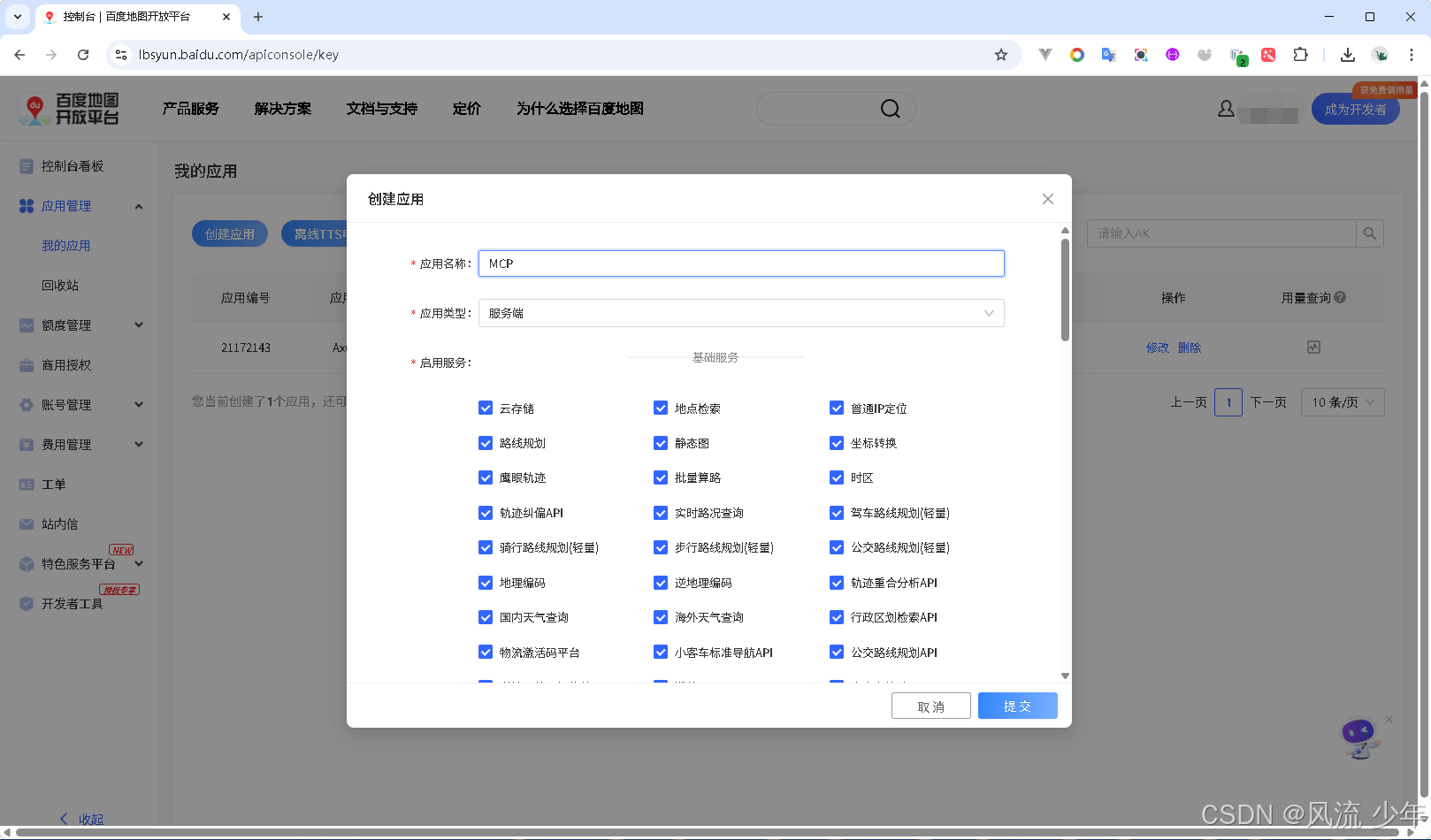

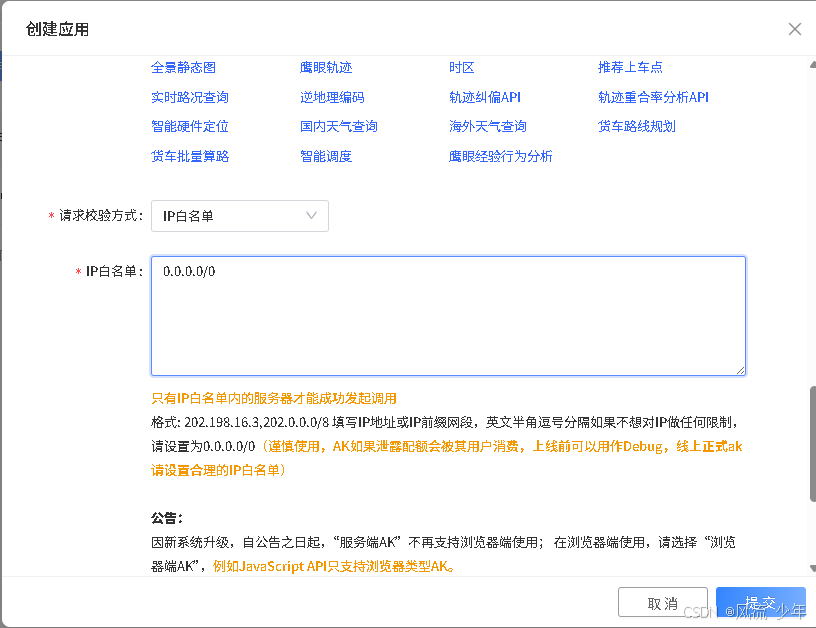

2.1.1 申请百度地图access-key

在百度地图开放平台创建应用获取AK(需要实名认证)。

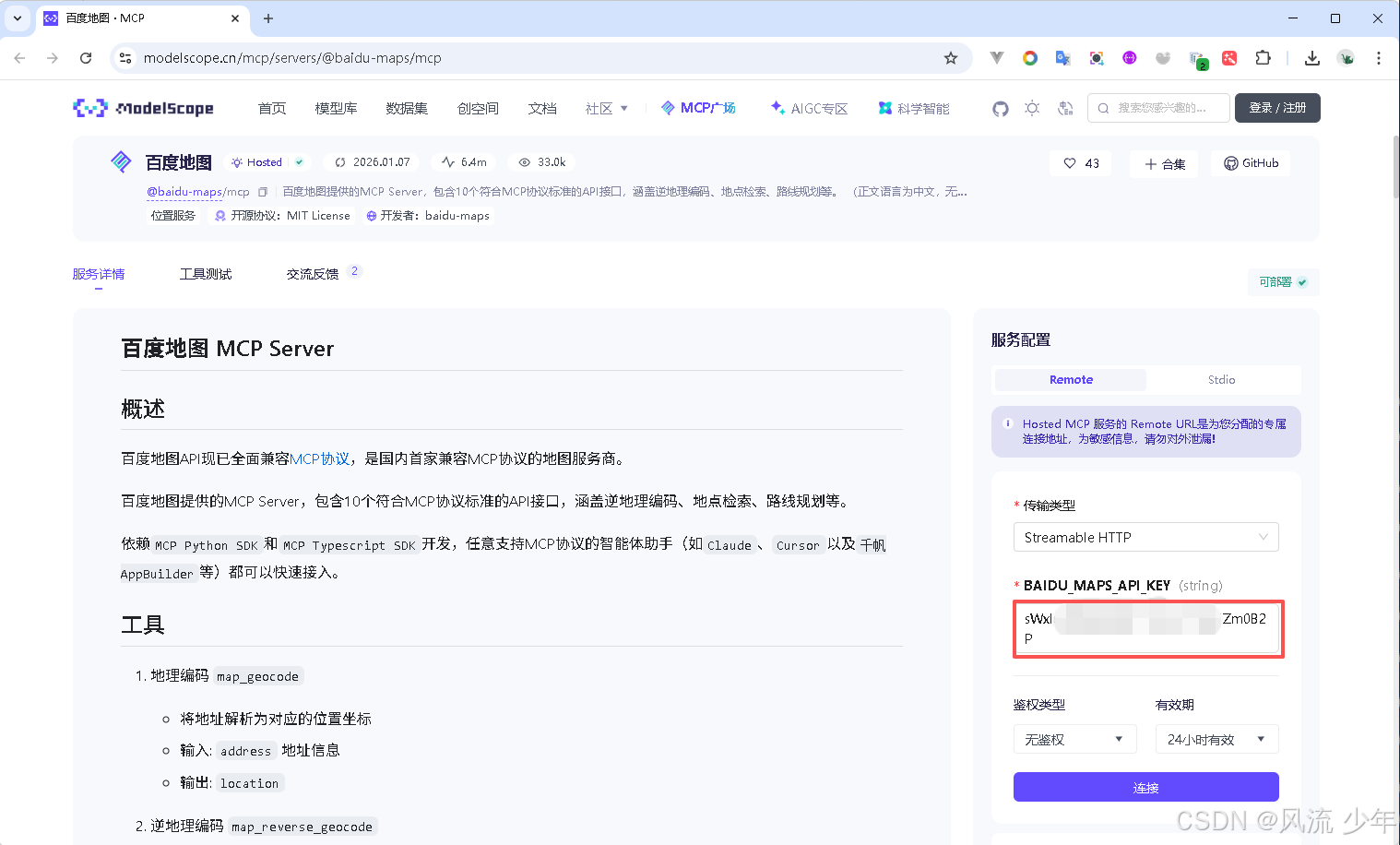

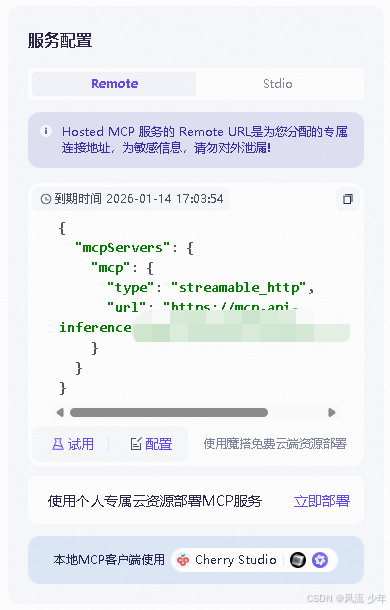

MCP Server 提供商 选择的是 ModelScope 的 MCP广场https://modelscope.cn/mcp,提供了非常丰富的 预部署的 MCP Server,这里尝试使用 百度地图 MCP服务,实现AI大模型的行程规划能力。在ModelScope - MCP 广场 中搜索“百度地图”,然后将上面获取到的访问应用(AK)粘贴到BAIDU_MAPS_API_KEY中进行连接测试API KEY是否可用,连接成功后会返回相应的mcpServer配置。

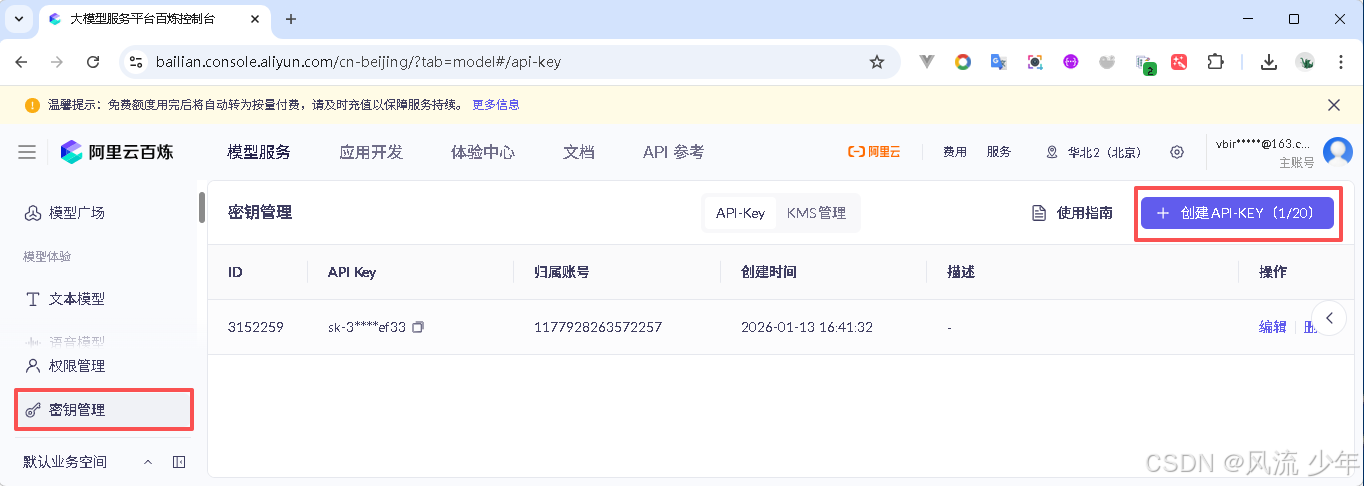

2.1.2 申请大模型API Key

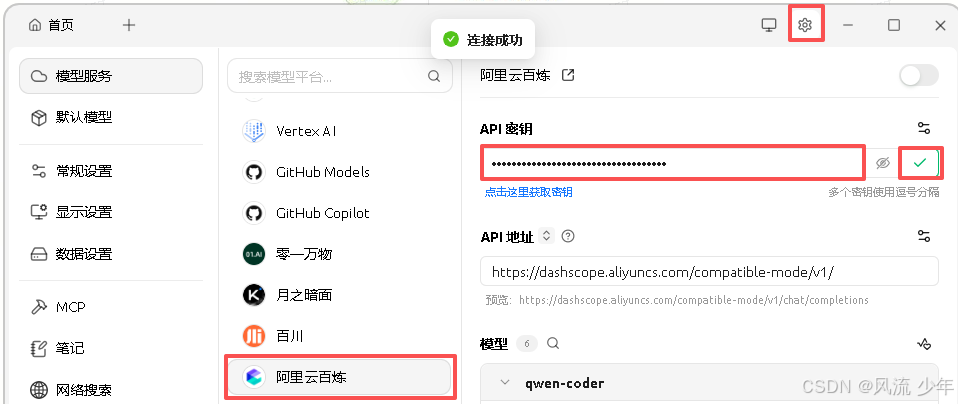

阿里云百炼 模型广场 新增密钥Api-key

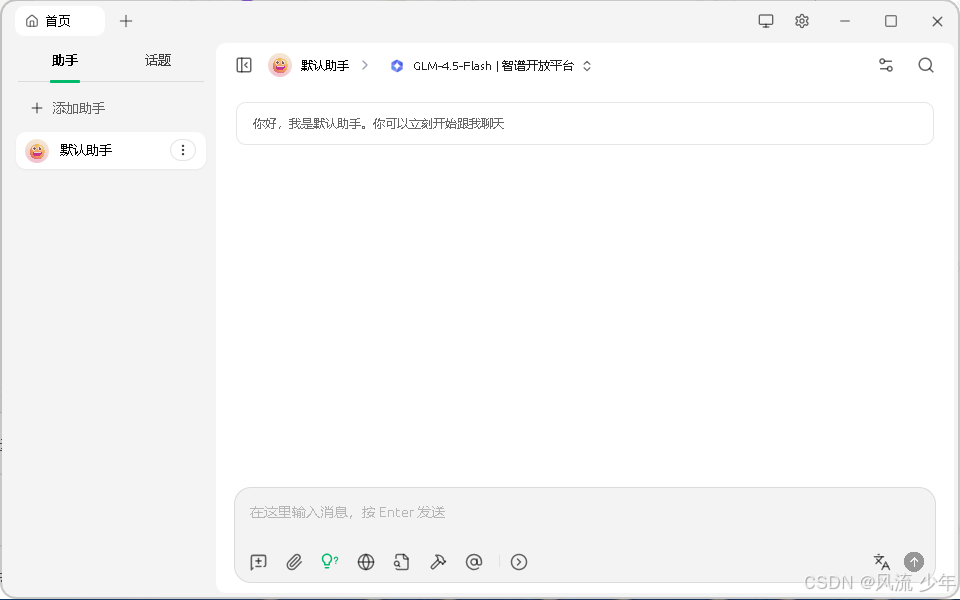

2.2 MCP 客户端( Cherry Studio )

2.2.1 下载Cherry Studio

https://www.cherry-ai.com/,用于测试MCP Server。

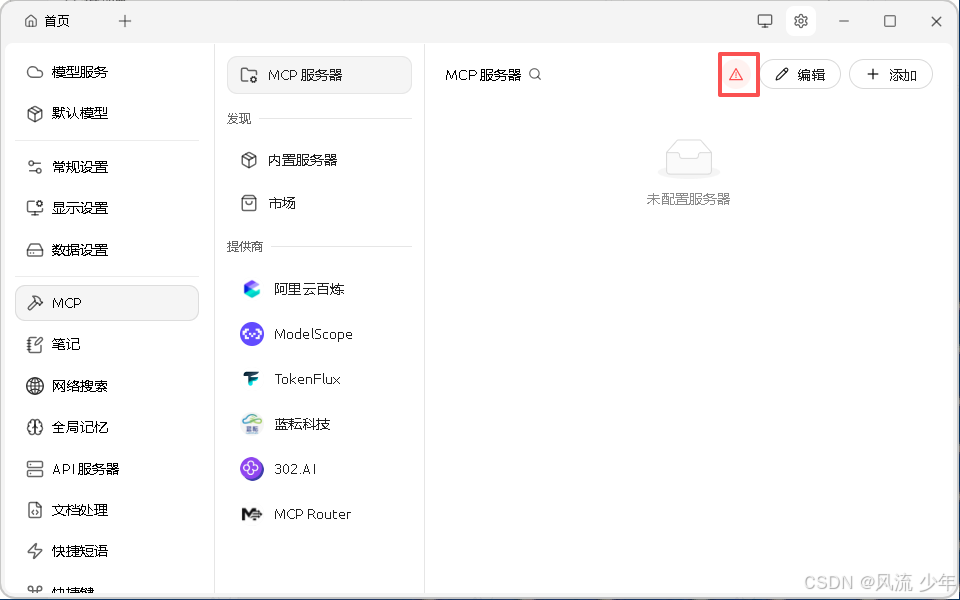

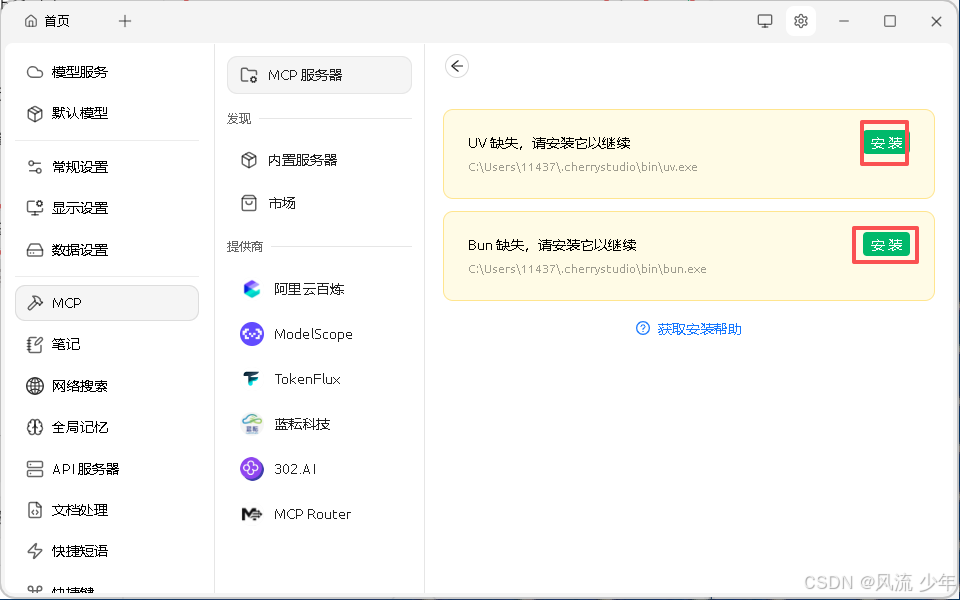

点击设置-MCP,如果有三角形红色警告,把缺失的安装完成。

2.2.2 配置阿里云百炼模型

将大模型服务平台中的API Key粘贴到API秘钥中并进行检测。

2.2.3 配置百度地图 MCP

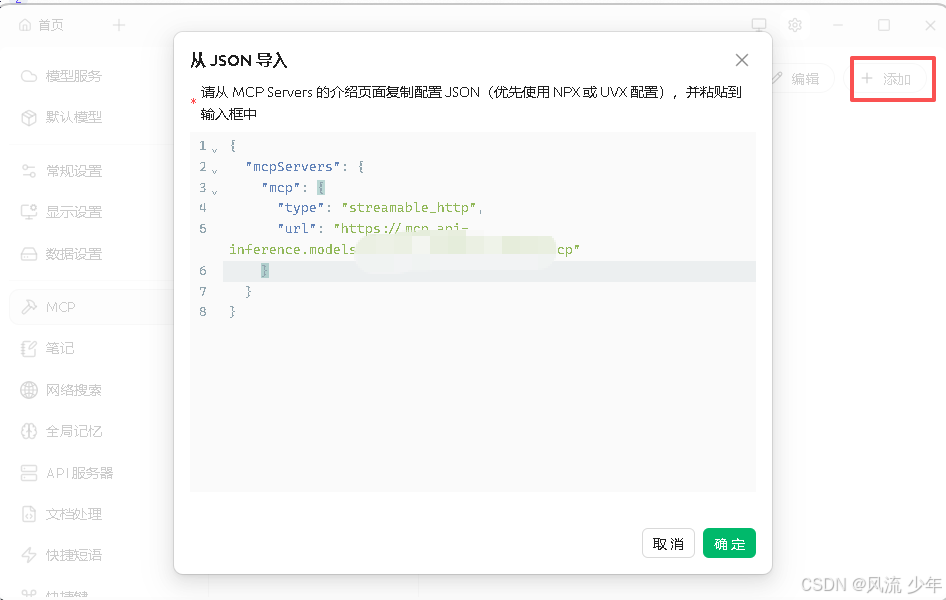

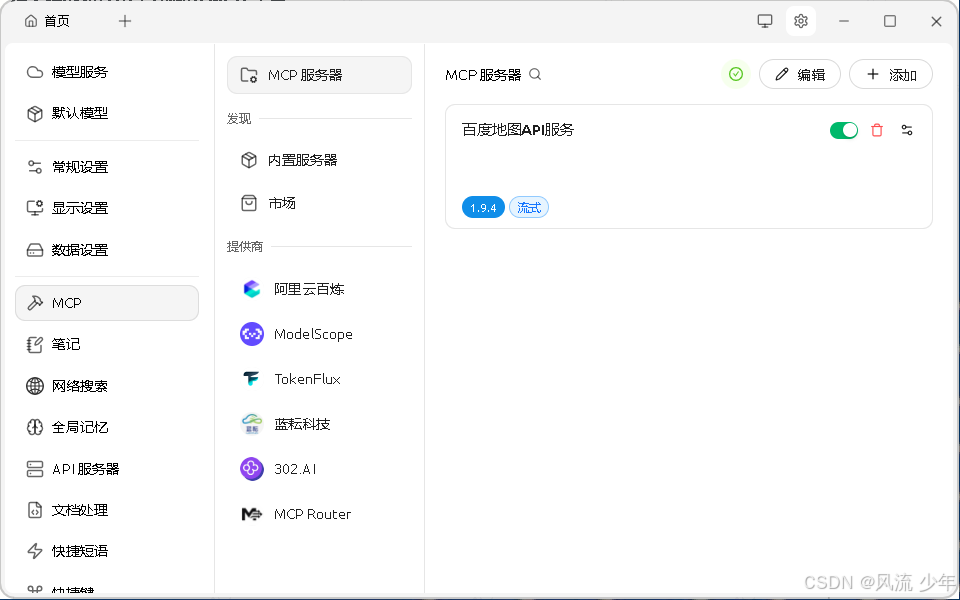

添加-从JSON导入,导入成功后可以修改一下名称。

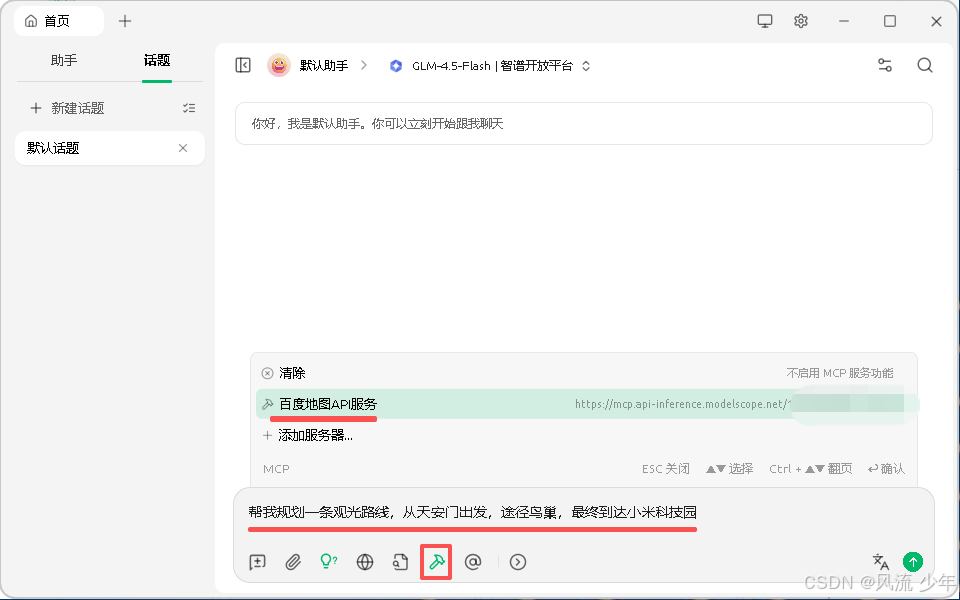

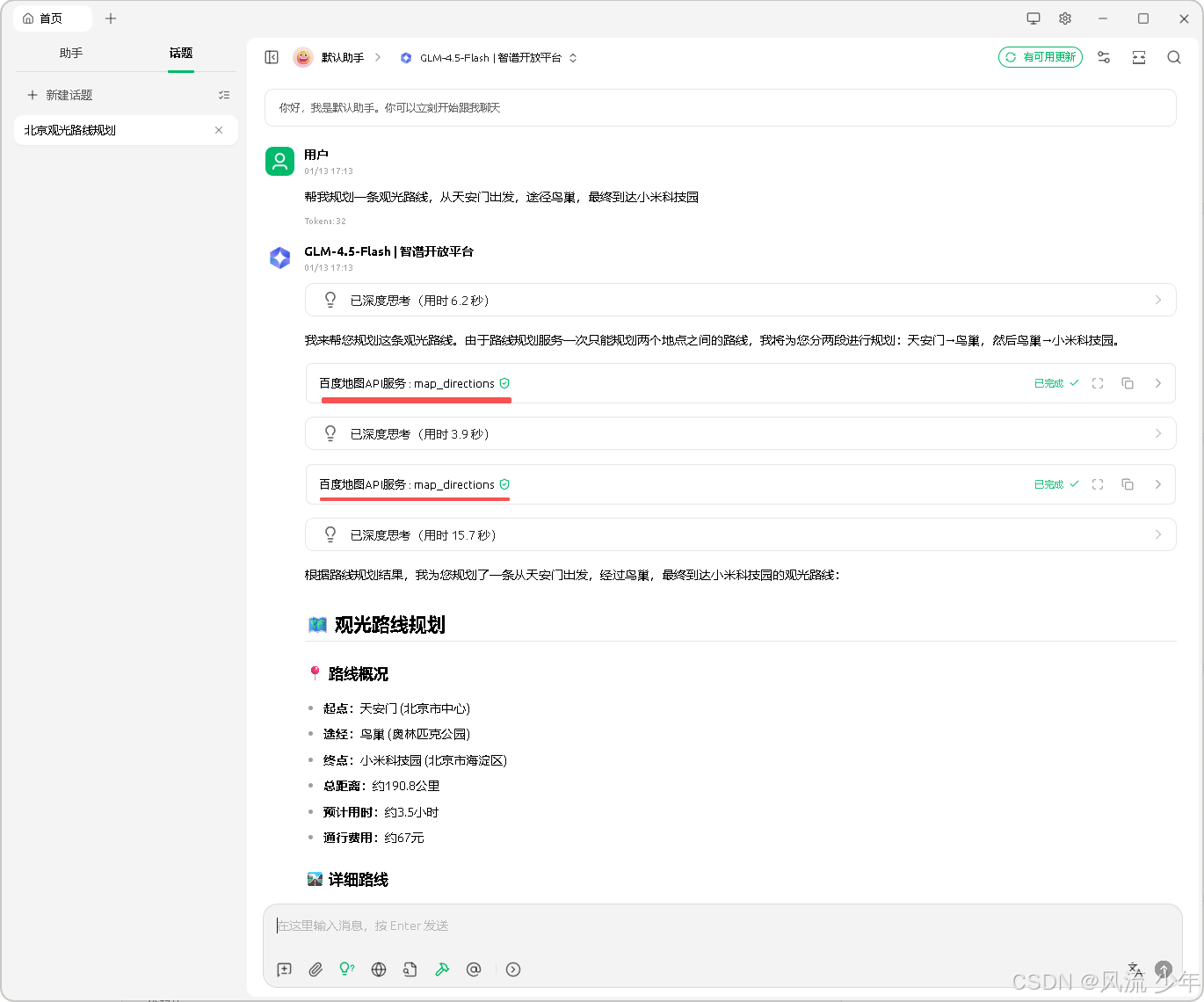

2.3 使用百度地图MCP

在首页中测试百度地图的MCP。发送,可以看到已经调用百度地图API服务了(先使用大模型进行语义分析获取每个地点,再调用百度地图获取 每个地点的位置,再使用大模型进行路线规划)。

三:自定义MCP服务(和风天气API)

3.0 环境准备

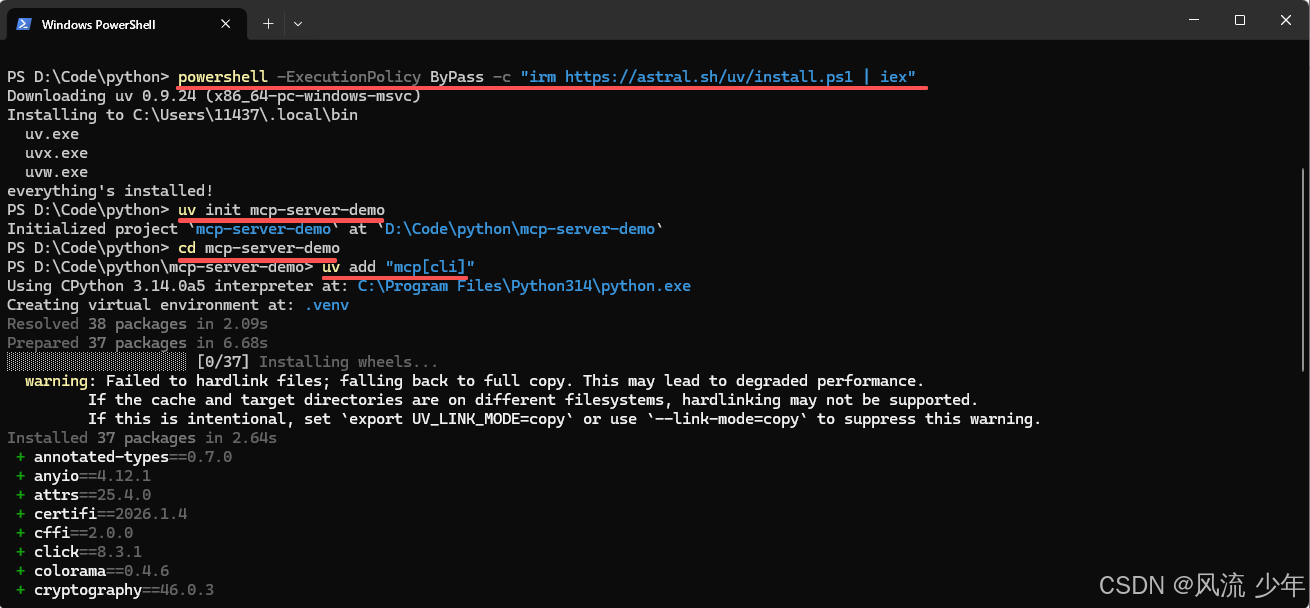

安装UV

官方推荐使用 uv 进行python项目管理,当然也提供了 pip 依赖的安装方式。

# macOS 以及 Lunux

curl -LsSf https://astral.sh/uv/install.sh | sh

# Windows

powershell -ExecutionPolicy ByPass -c "irm https://astral.sh/uv/install.ps1 | iex"

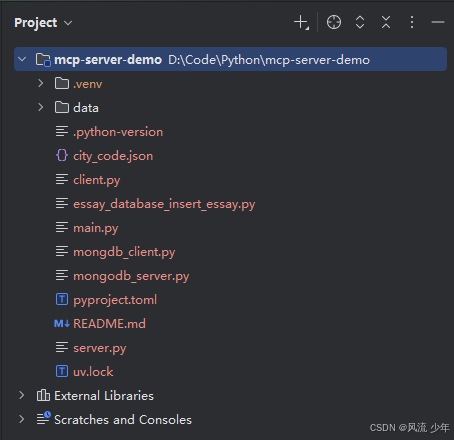

初始化项目

uv init mcp-server-demo

cd mcp-server-demo

uv init mcp-server-demo 会在当前目录下创建 mcp-server-demo 文件夹,并初始化项目,包括main.py,uv.lock,.python-version等项目管理需要的文件。

安装依赖

# uv方式

uv add "mcp[cli]"

# pip方式

pip install "mcp[cli]"

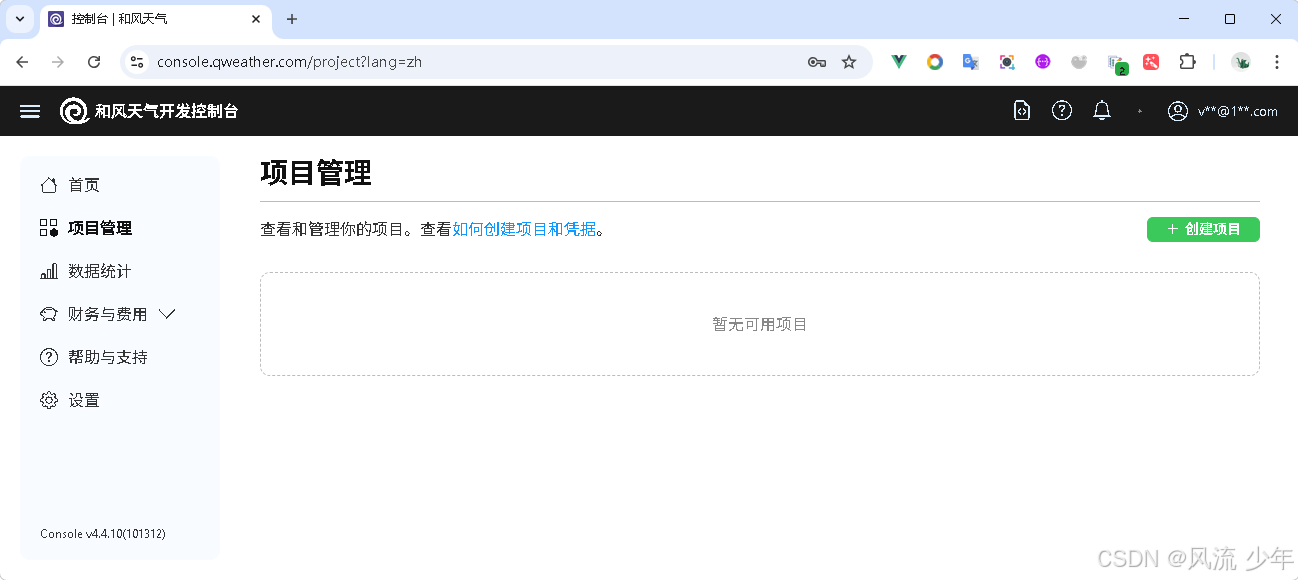

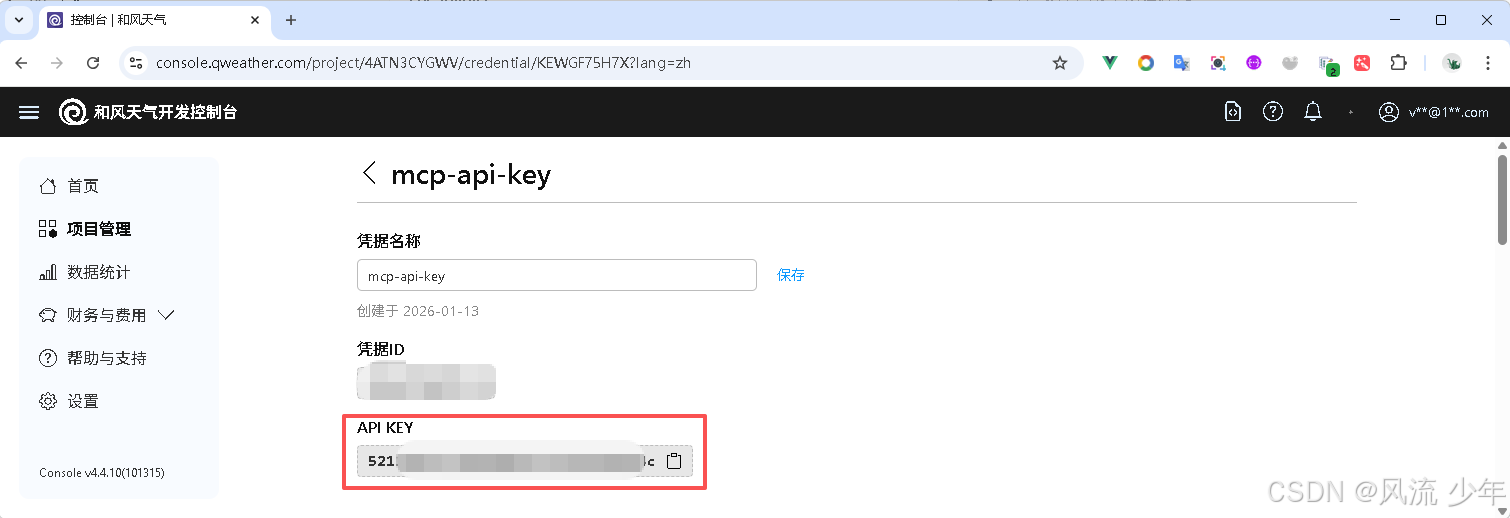

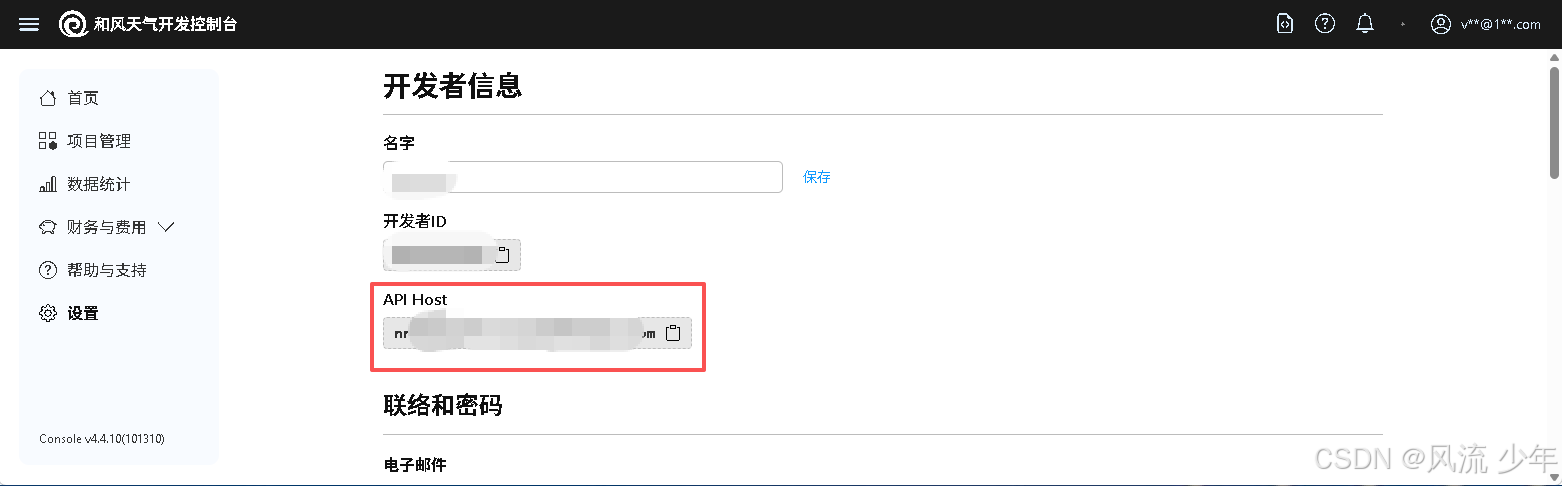

申请和风天气

https://console.qweather.com/ 创建项目,获取API Host和API KEY

设置 - 开发者信息 - API Host

3.1 MCP Server

3.1.1 server.py

HeFeng_BASE_URL 和 HeFeng_API_KEY 需要替换上面的API Host、API KEY。

import json

import os

from mcp.server.fastmcp import FastMCP

import requests

HeFeng_BASE_URL = "https://xxxx.re.qweatherapi.com"

HeFeng_API_KEY = "5211e0??????????????????34c"

CITY_CODE_FILE = "city_code.json"

SERVER_PORT = 9001

MODE="stdio" # stdio or sse

# Create an MCP server

if (MODE == "sse"):

mcp = FastMCP("Weather", port=SERVER_PORT)

else:

mcp = FastMCP("Weather")

# 工具,获取城市码

def get_city_code(city: str) -> str:

API = "/geo/v2/city/lookup?location="

try:

# 首先尝试从本地文件读取

city_code_dict = {}

if os.path.exists(CITY_CODE_FILE):

with open(CITY_CODE_FILE, "r", encoding='utf-8') as f:

city_code_dict = json.load(f)

# 如果城市代码存在,直接返回

if city in city_code_dict:

return city_code_dict[city]

# 如果城市代码不存在,从网络获取

url = HeFeng_BASE_URL + API + city

headers = {

"X-QW-Api-Key":HeFeng_API_KEY

}

response = requests.get(url, headers=headers)

if response.status_code == 200:

data = response.json()

if data['code'] == '200' and data['location']:

city_code = data['location'][0]['id']

# 更新本地文件

city_code_dict[city] = city_code

with open(CITY_CODE_FILE, "w", encoding='utf-8') as f:

json.dump(city_code_dict, f, ensure_ascii=False, indent=4)

return city_code

else:

raise Exception(f"未找到城市 {city} 的代码")

else:

raise Exception("网络请求失败")

except Exception as e:

raise Exception(f"获取城市代码失败: {str(e)}")

# MCP服务方法,获取城市的当前天气

@mcp.tool()

def get_current_weather(city: str) -> str:

"""

输入指定城市的中文名称,返回城市的当前天气信息

:param city: 城市的中文名称

:return: 城市的当前天气信息

"""

API = "/v7/weather/now?location="

city_code = get_city_code(city)

url = HeFeng_BASE_URL + API + city_code

headers = {

"X-QW-Api-Key":HeFeng_API_KEY

}

response = requests.get(url, headers=headers)

if response.status_code == 200:

data = response.json()

if data['code'] == '200' and data['now']:

weather_info = data['now']

responseStr = f"当前城市: {city}"

responseStr += f"\n天气: {weather_info['text']}"

responseStr += f"\n温度: {weather_info['temp']}°C"

responseStr += f"\n体感温度: {weather_info['feelsLike']}°C"

responseStr += f"\n风力风向: {weather_info['windDir']} {weather_info['windScale']}级"

responseStr += f"\n相对湿度: {weather_info['humidity']}%"

return responseStr

else:

return f"未找到城市 {city} 的天气信息"

else:

return "网络请求失败"

import sys

# 添加启动日志(输出到 stderr,避免干扰 stdio 通信)

print("MCP Server starting...", file=sys.stderr)

print(f"Transport mode: {MODE}", file=sys.stderr)

print(f"Working directory: {os.getcwd()}", file=sys.stderr)

mcp.run(transport=MODE)

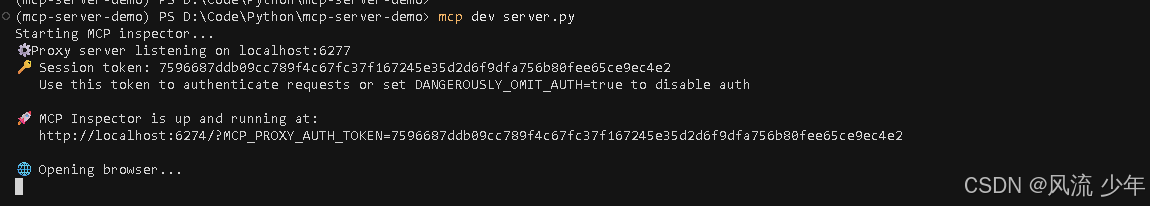

3.1.2 启动server.py

# 安装inspector

npm install -g @modelcontextprotocol/inspector

# 如果启动报错直接让AI修复提示词:uv run mcp dev server.py启动没有输出任何内容,并且http://localhost:6274无法访问

# 运行成功后会自动打开浏览器 http://localhost:6274/?MCP_PROXY_AUTH_TOKEN=xxx

mcp dev server.py

注意:一定要看到Starting MCP insepector…

3.1.3 调试工具

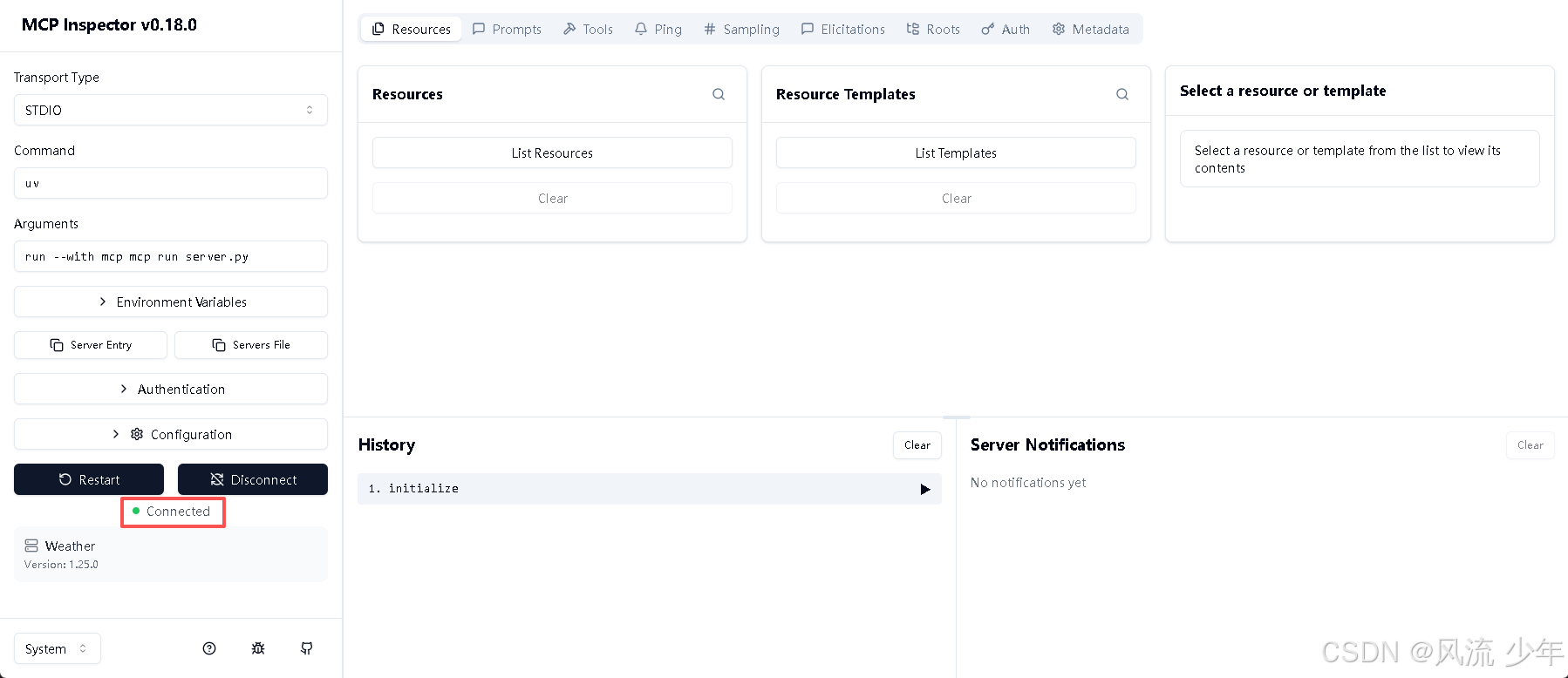

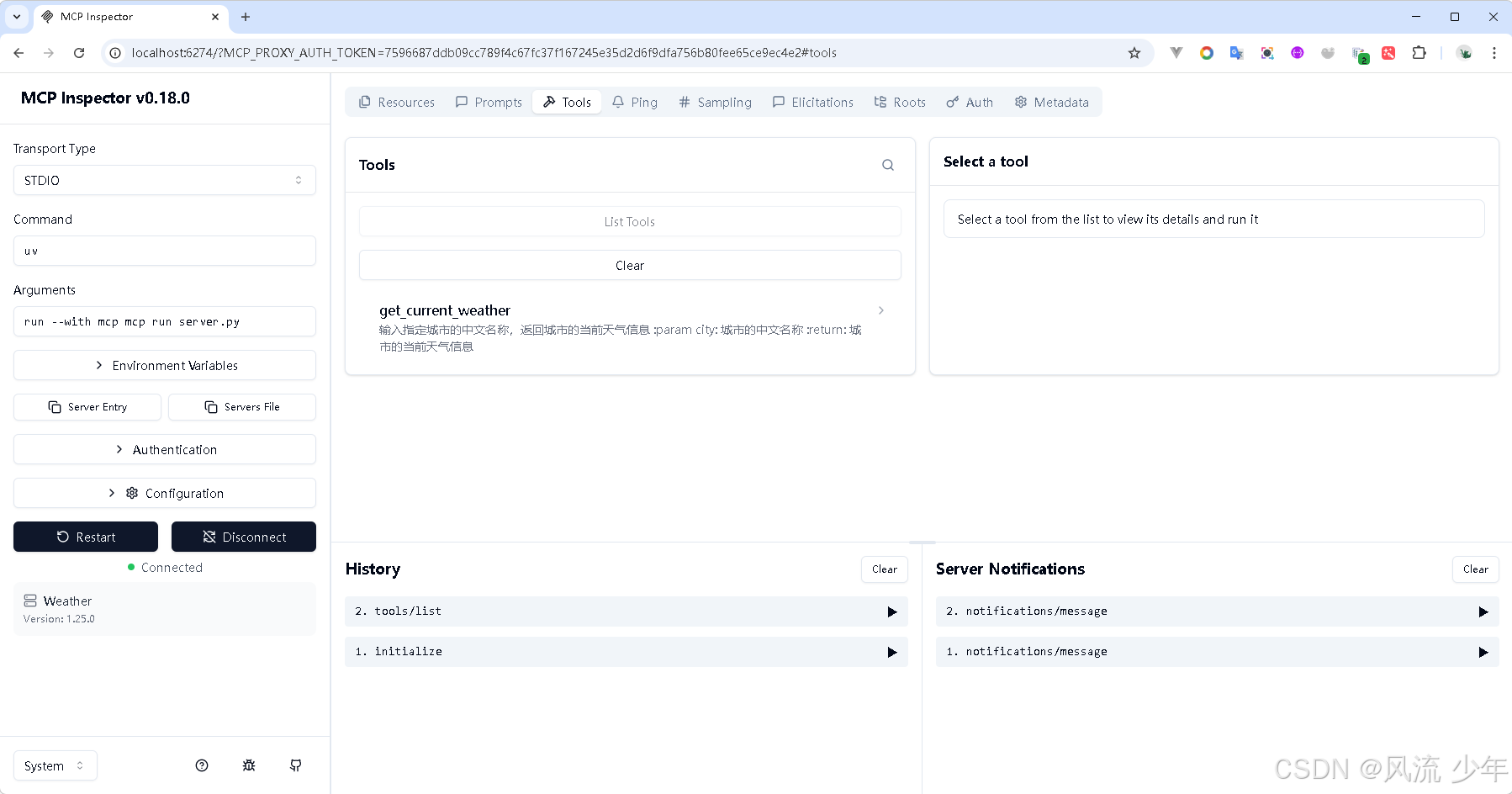

点击Connect进行连接,连接成功后为Connected,

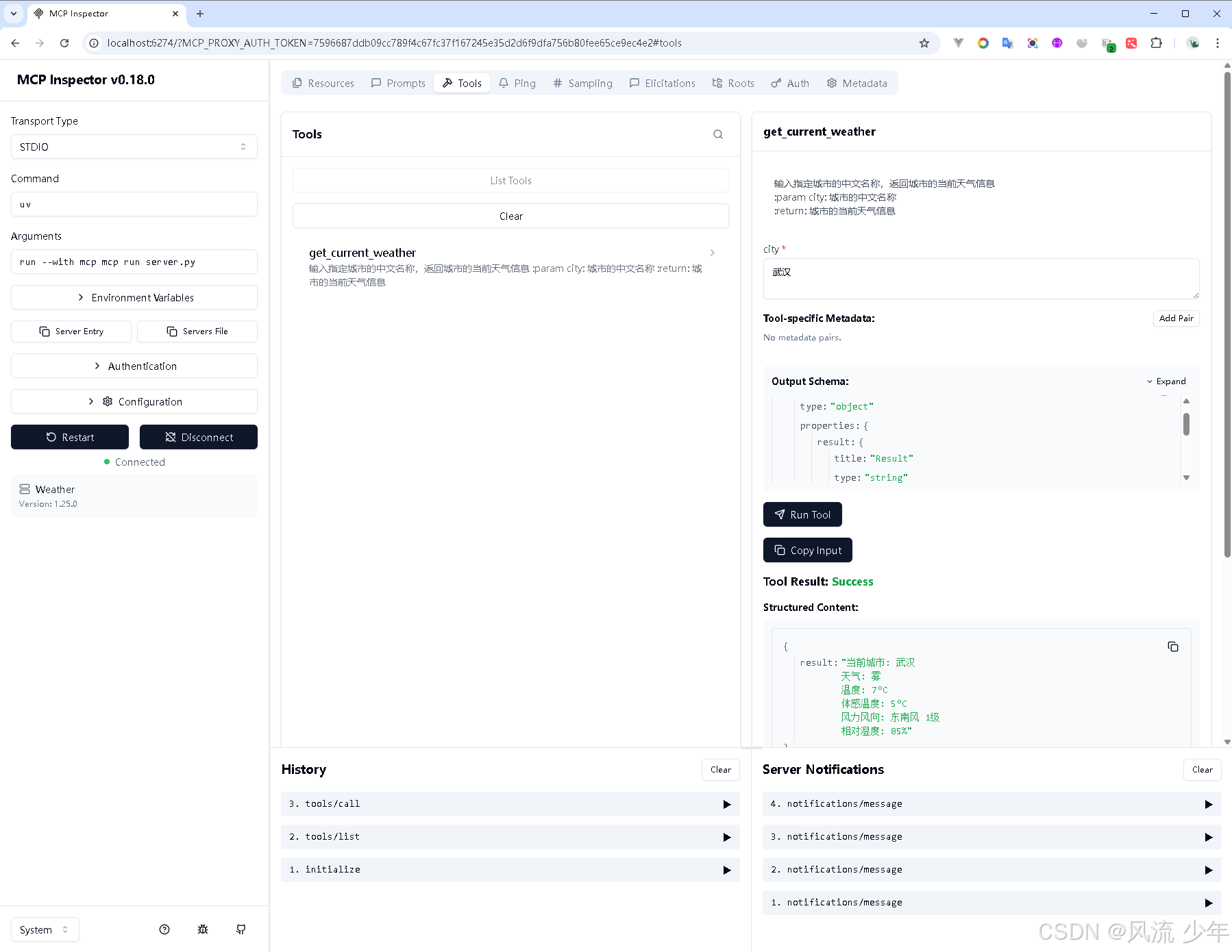

此时MCP Inspector会暴露我们代码中公开的Resources,Prompts和Tools,由于我们目前只定义了一个 @mcp.tool(),所以可以直接进入Tools标签页,点击 List Tools 即可看到我们刚刚创建的工具,以及工具描述。

点击工具名称,就可以在右边开始调试server.py中的tool了。

3.2 MCP Client

3.2.1 下载Ollama

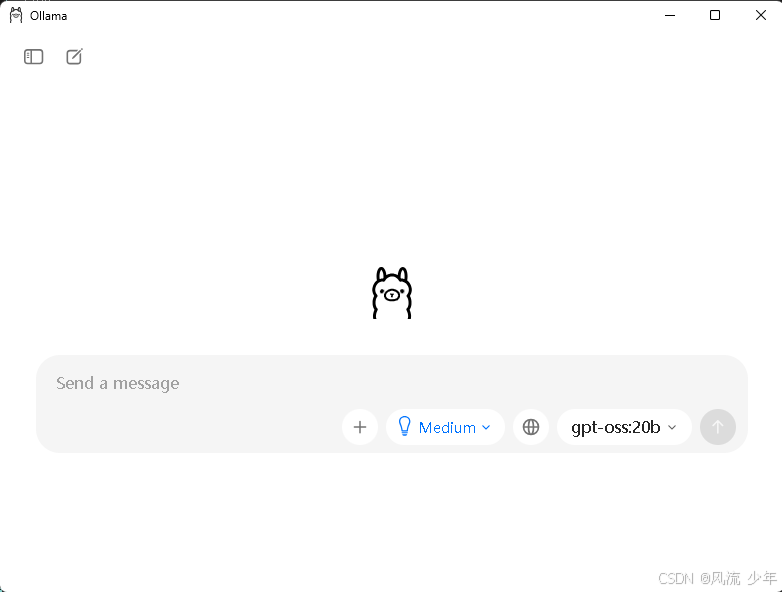

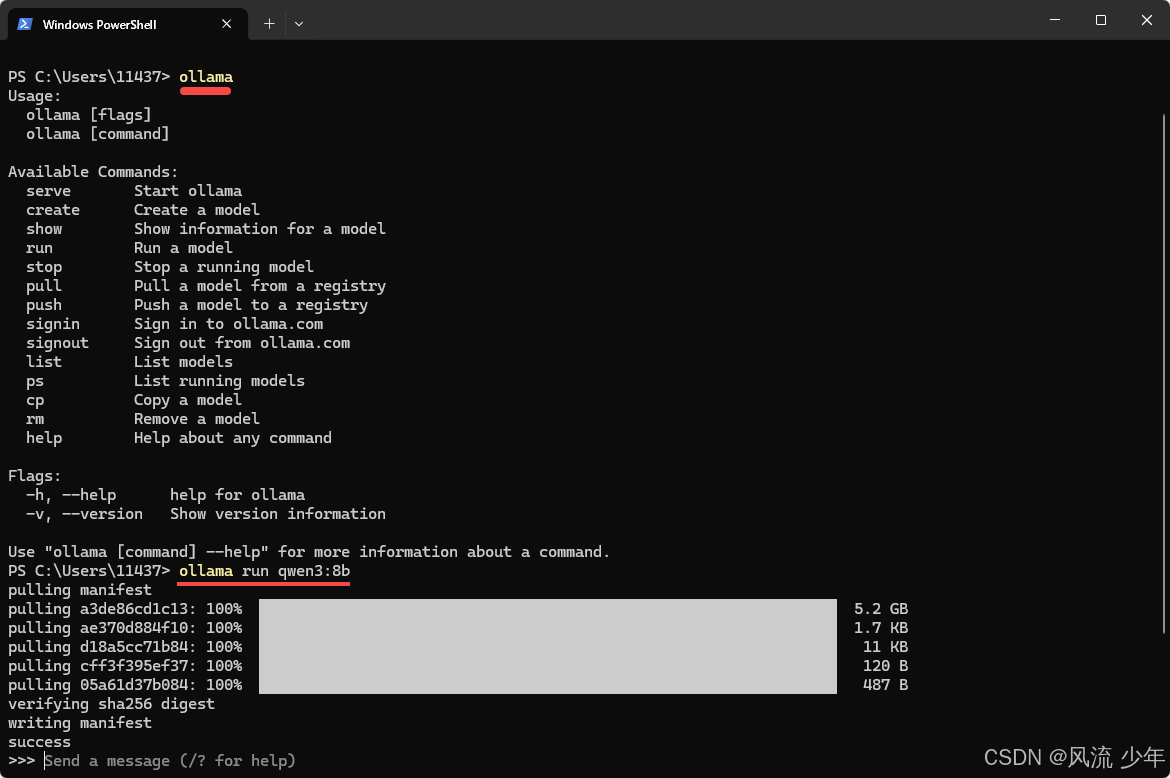

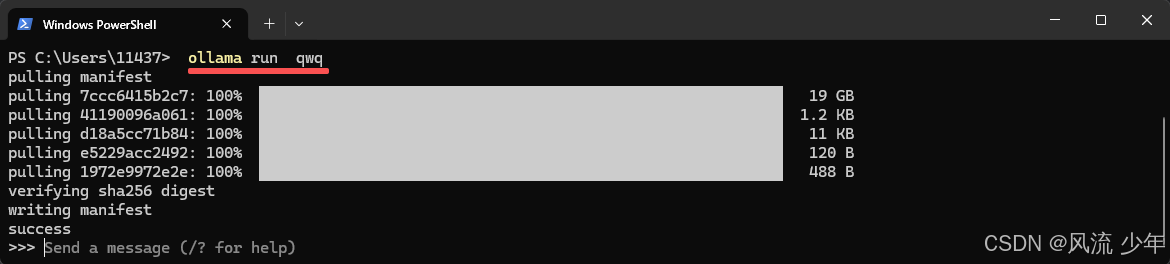

从官网下载 Ollama 推理框架 https://ollama.com/download

安装完成后下载模型 ollama run qwen3:8b (5G大小),最好下载qwq模型,而qwen3:8在后面使用时会超时。

ollama run qwq(建议,19G大小)

下载完成后就可以选择qwq。

3.3.2 client.py

注意:安装必要的依赖,os.getenv(“OLLAMA_MODEL”, “qwen3:8b”) 中的模型名字和上面的模型名字保持一致。

import asyncio

import os

import sys

import json

from typing import Optional

from contextlib import AsyncExitStack

from openai import OpenAI

from dotenv import load_dotenv

from mcp import ClientSession, StdioServerParameters

from mcp.client.stdio import stdio_client

class MCPClient:

def __init__(self):

"""初始化MCP客户端"""

load_dotenv()

self.exit_stack = AsyncExitStack()

# Ollama 的 OpenAI 兼容端点

base_url = os.getenv("OLLAMA_BASE_URL", "http://localhost:11434/v1")

# 修改为 OpenAI 兼容的基础 URL

if "/api/generate" in base_url:

base_url = base_url.replace("/api/generate", "")

self.model = os.getenv("OLLAMA_MODEL", "qwen3:8b")

# 初始化 OpenAI 客户端

self.client = OpenAI(

base_url=base_url,

api_key="ollama" # Ollama 不需要真正的 API 密钥,但 OpenAI 客户端需要一个非空值

)

self.session: Optional[ClientSession] = None

async def connect_to_server(self, server_script_path: str):

"""连接到 MCP 服务器并列出可用工具"""

is_python = server_script_path.endswith(".py")

is_js = server_script_path.endswith(".js")

if not (is_python or is_js):

raise ValueError("服务器脚本必须是 Python 或 JavaScript 文件")

# 使用 stdio_client 连接到 MCP 服务器

command = "python" if is_python else "node"

print(f"使用命令: {command} {server_script_path}")

server_params = StdioServerParameters(

command=command,

args=[server_script_path],

env=None

)

# 启动 MCP 服务器并建立通讯

stdio_transport = await self.exit_stack.enter_async_context(stdio_client(server_params))

self.stdio, self.write = stdio_transport

self.session = await self.exit_stack.enter_async_context(ClientSession(self.stdio, self.write))

await self.session.initialize()

# 列出 MCP 服务器上的工具

response = await self.session.list_tools()

tools = response.tools

print("\n可用工具:")

for tool in tools:

print(f" {tool.name}: {tool.description}")

async def process_query(self, query: str) -> str:

"""使用 OpenAI 客户端调用 Ollama API 处理用户查询"""

messages = [{"role": "user", "content": query}]

response = await self.session.list_tools()

available_tools = [{

"type": "function",

"function": {

"name": tool.name,

"description": tool.description,

"input_schema": tool.inputSchema

}

} for tool in response.tools]

try:

# 使用 OpenAI 客户端请求

response = await asyncio.to_thread(

lambda: self.client.chat.completions.create(

model=self.model,

messages=messages,

tools = available_tools

)

)

# 从响应中提取文本

content = response.choices[0]

if content.finish_reason == "tool_calls":

# 如果是需要实用工具,就解析工具

tool_call = content.message.tool_calls[0]

tool_name = tool_call.function.name

tool_args = json.loads(tool_call.function.arguments)

# 执行工具

result = await self.session.call_tool(tool_name, tool_args)

print(f"\n\n工具 {tool_name} 参数 {tool_args} 返回结果: {result}\n\n")

# 将模型返回的工具数据和执行结果都存入message中

messages.append(content.message.model_dump())

messages.append({

"role": "tool",

"content": result.content[0].text,

"tool_call_id": tool_call.id

})

# 将上述结果再返回给大模型用于生成最终结果

response = self.client.chat.completions.create(

model=self.model,

messages=messages

)

return response.choices[0].message.content

except Exception as e:

import traceback

# 收集详细错误信息

error_details = {

"异常类型": type(e).__name__,

"异常消息": str(e),

"请求URL": self.client.base_url,

"请求模型": self.model,

"请求内容": query[:100] + "..." if len(query) > 100 else query

}

print(f"Ollama API 调用失败:详细信息如下:")

for key, value in error_details.items():

print(f" {key}: {value}")

print("\n调用堆栈:")

traceback.print_exc()

return "抱歉,发生未知错误,我暂时无法回答这个问题。"

async def chat_loop(self):

"""交互式聊天循环"""

print("\n欢迎使用MCP客户端!输入 'quit' 退出")

while True:

try:

query = input("\n你: ").strip()

if query.lower() == 'quit':

print("再见!")

break

response = await self.process_query(query)

print(f"\nOllama: {response}")

except Exception as e:

print(f"\n发生错误:{e}")

async def cleanup(self):

"""清理资源"""

await self.exit_stack.aclose()

async def main():

if (len(sys.argv) < 2) :

print("请提供MCP服务器的脚本路径")

sys.exit(1)

client = MCPClient()

try:

await client.connect_to_server(sys.argv[1])

await client.chat_loop()

finally:

await client.cleanup()

if __name__ == "__main__":

asyncio.run(main())

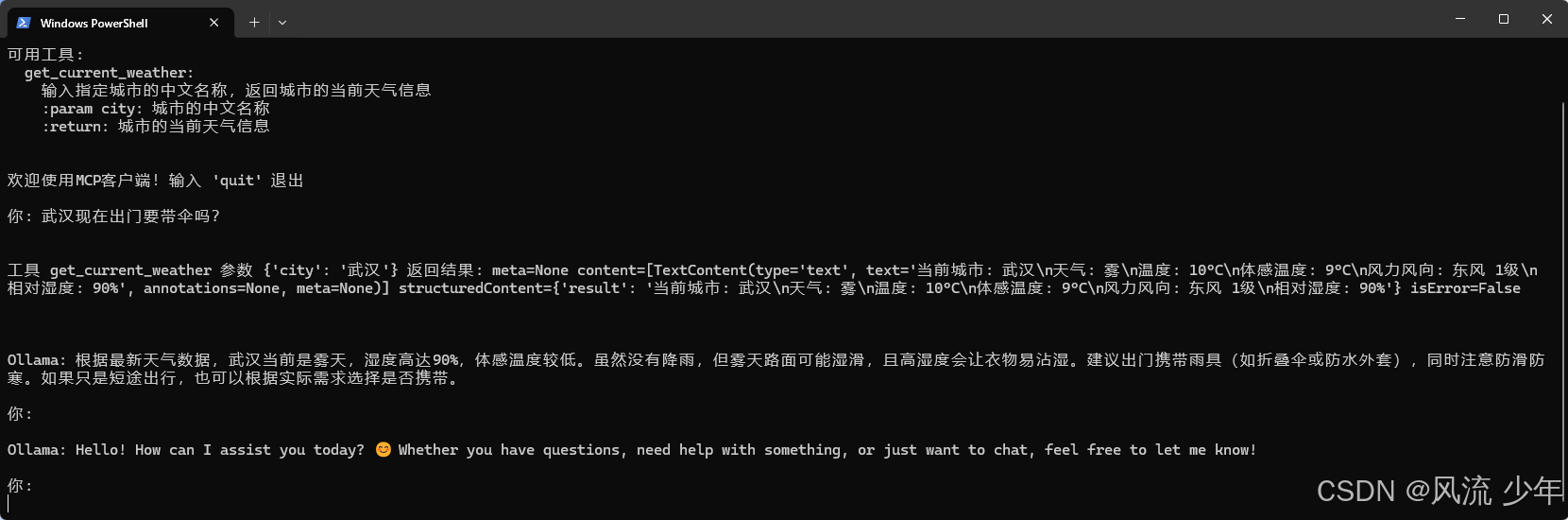

同时启动客户端和服务端。

uv run python client.py server.py

可以看到大模型成功提取出了工具需要的关键字,调用了工具,并依据工具的返回结果进行了最终推理(注意:回答 可能很慢,看机器配置,等几分钟,只要不报错就静静等待)。

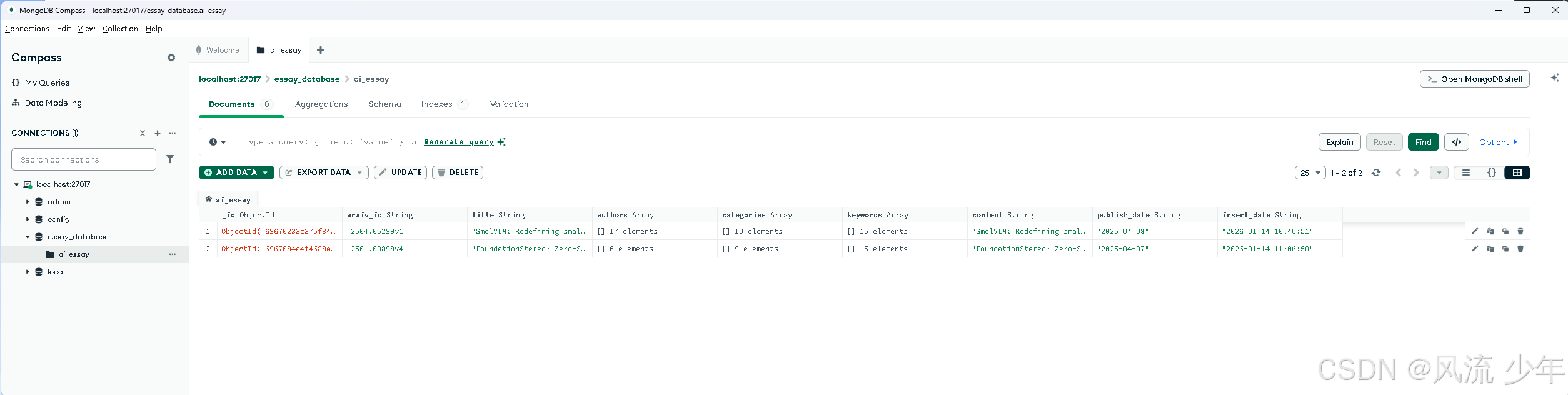

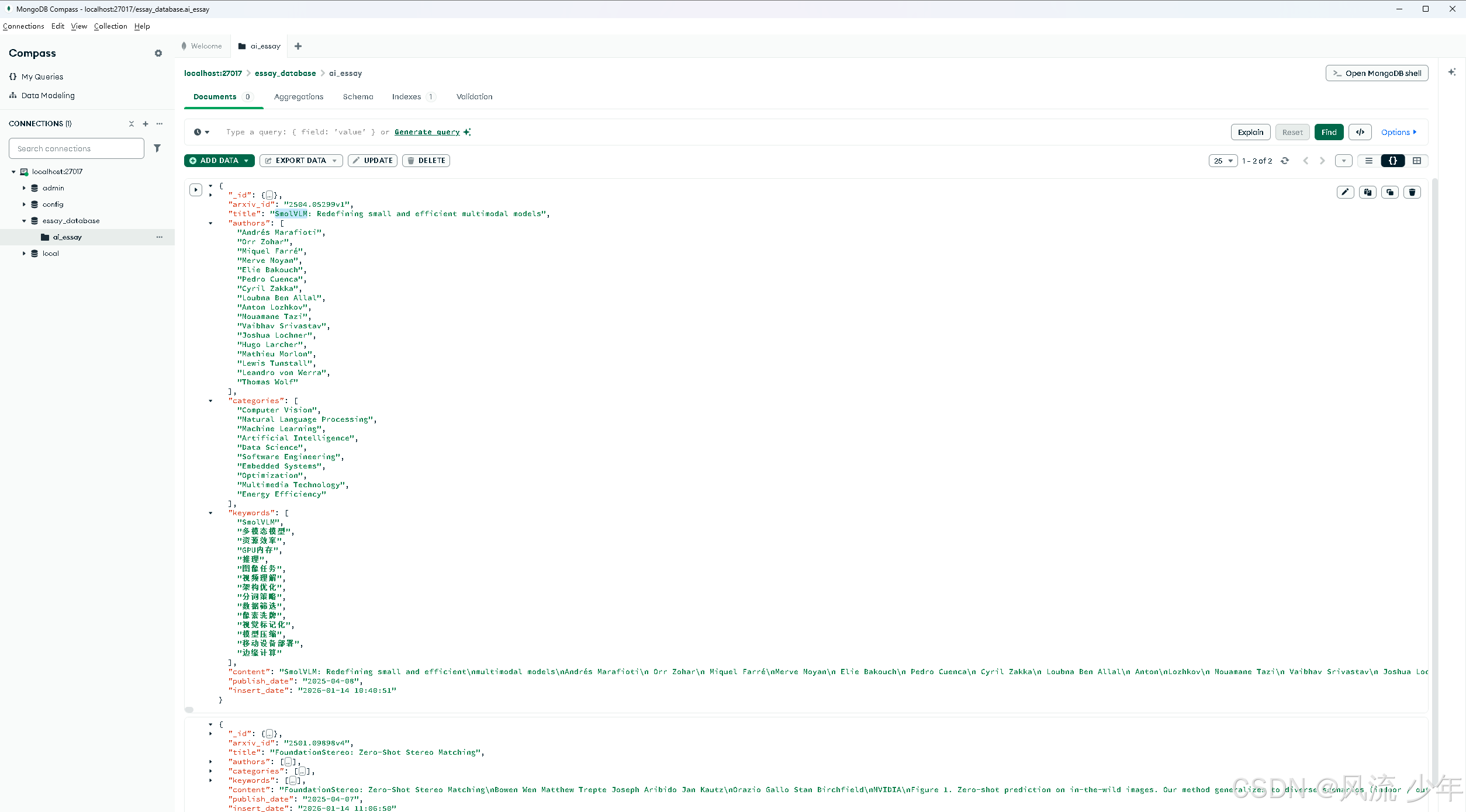

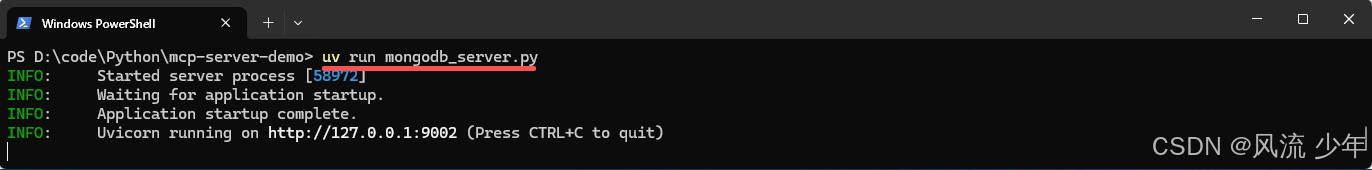

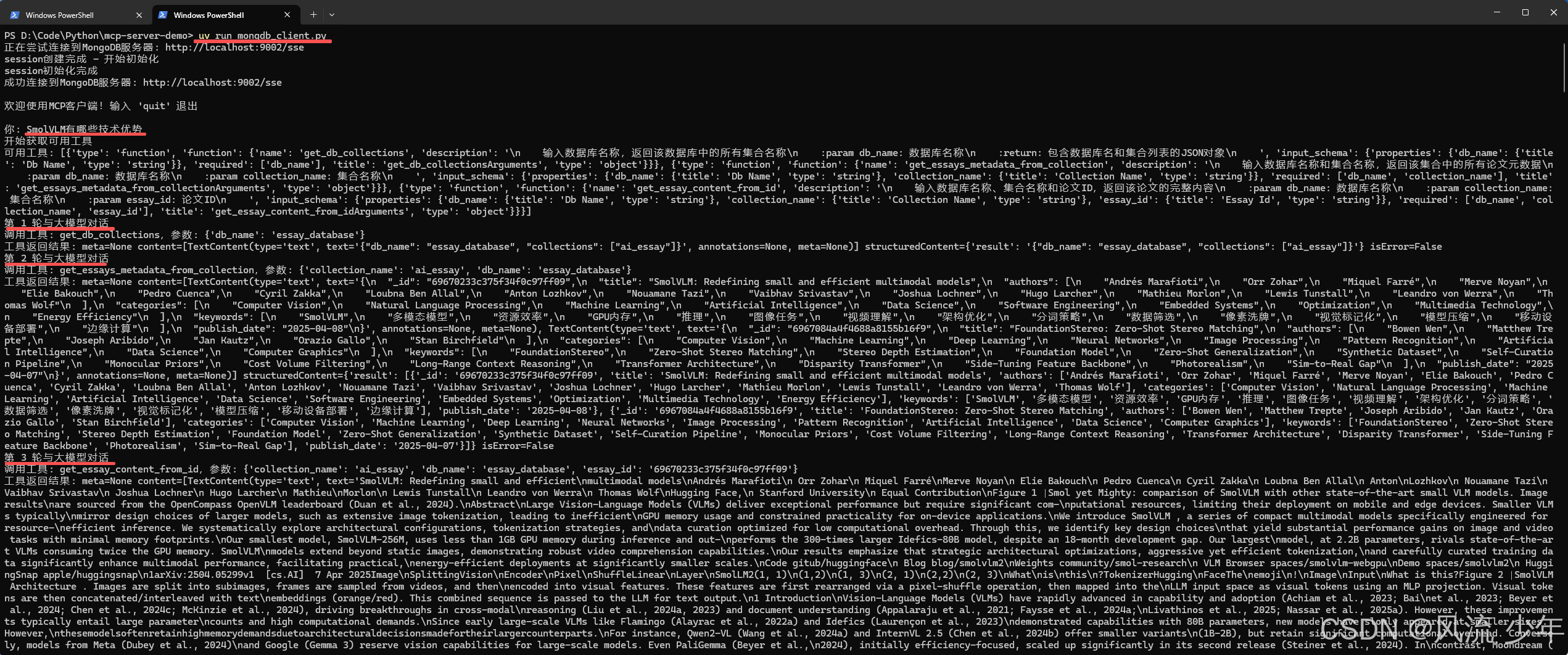

四:自定义MCP服务(MongoDB数据库)

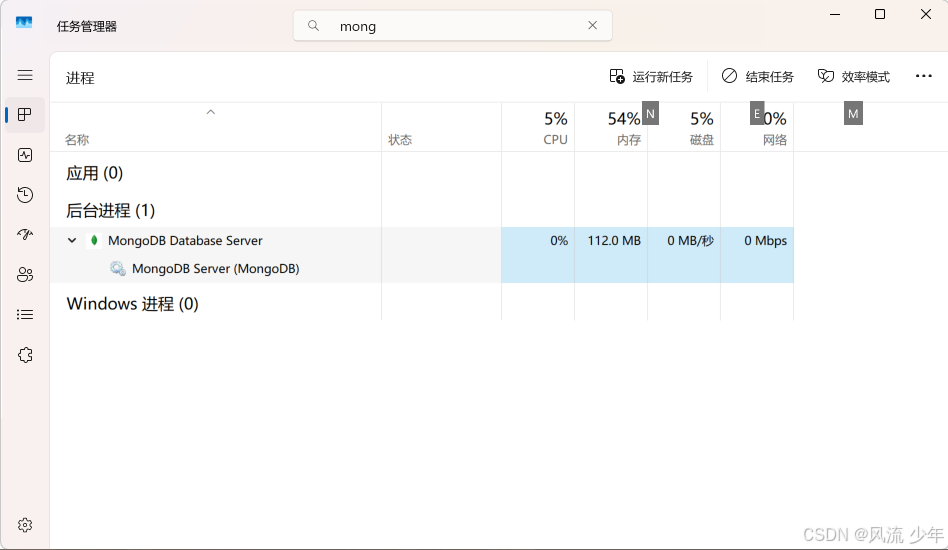

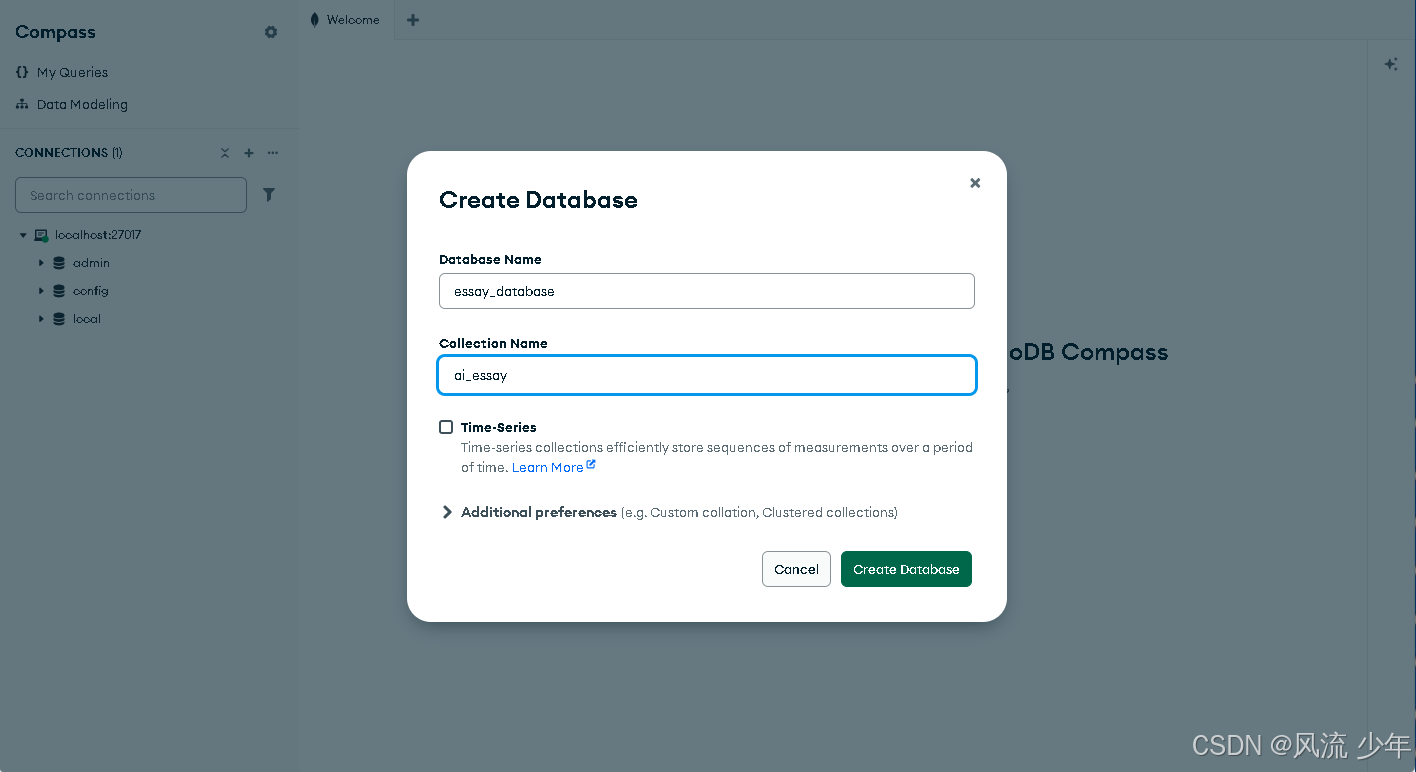

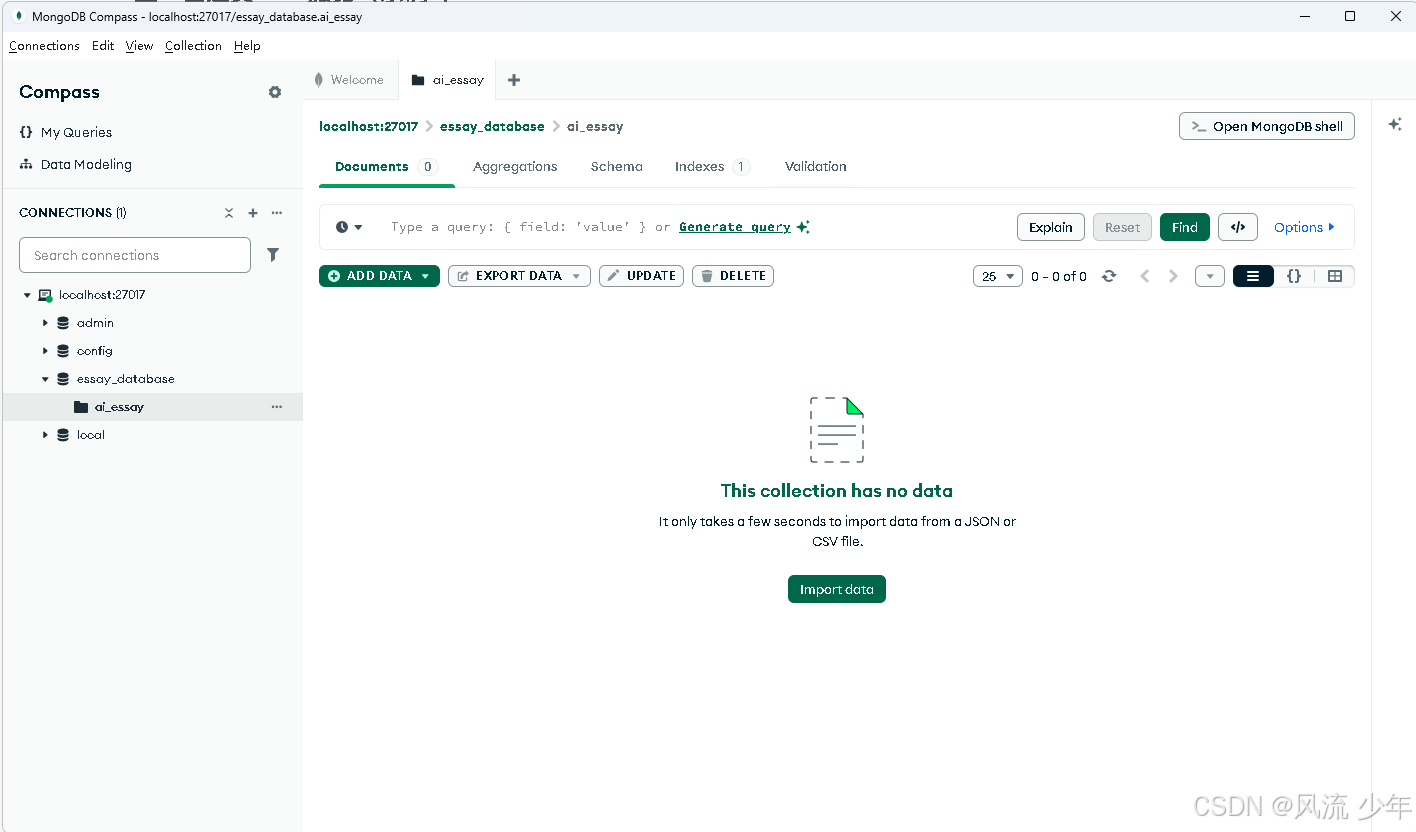

4.0 环境准备

MongoDB社区版下载安装 https://www.mongodb.com/try/download/community

MongoDB GUI工具下载安装 https://www.mongodb.com/try/download/terraform-provider

启动MongoDB数据库。

4.1 数据准备

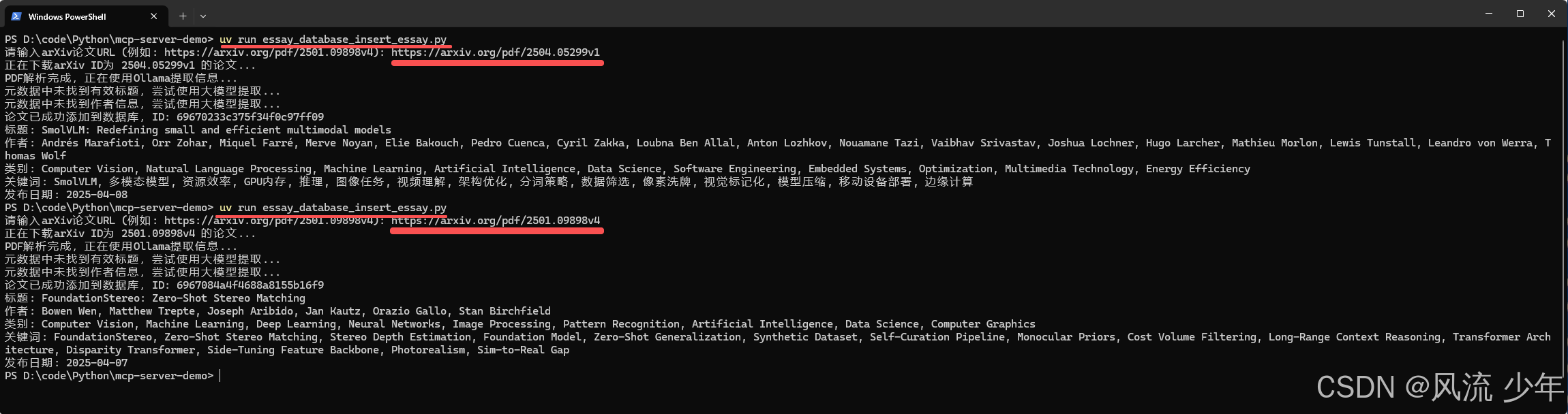

essay_database_insert_essay.py:输入 arxiv.org 论文的链接,获取论文内容,解析整理并存入本地的 MongoDB 数据库。

import re

import os

import requests

import io

import json

import pymongo

import datetime

from urllib.parse import urlparse

from pymongo import MongoClient

from PyPDF2 import PdfReader

from dotenv import load_dotenv

# 加载环境变量

load_dotenv()

# MongoDB连接设置

MONGO_URI = os.getenv("MONGO_URI", "mongodb://localhost:27017/")

DB_NAME = os.getenv("DB_NAME", "essay_database")

COLLECTION_NAME = os.getenv("COLLECTION_NAME", "ai_essay")

# Ollama设置

OLLAMA_BASE_URL = os.getenv("OLLAMA_BASE_URL", "http://localhost:11434/api")

OLLAMA_MODEL = os.getenv("OLLAMA_MODEL", "qwen3:8b")

def connect_to_mongodb():

"""连接到MongoDB数据库"""

try:

client = MongoClient(MONGO_URI)

db = client[DB_NAME]

collection = db[COLLECTION_NAME]

return collection

except Exception as e:

print(f"MongoDB连接错误: {e}")

return None

def extract_arxiv_id(url):

"""从URL中提取arXiv ID"""

# 移除URL中的http://或https://前缀,如果存在

url = url.strip()

if url.startswith(('http://', 'https://')):

parsed = urlparse(url)

url = parsed.netloc + parsed.path

# 从URL中提取arXiv ID

match = re.search(r'arxiv\.org/pdf/(\d+\.\d+)(v\d+)?', url)

if match:

arxiv_id = match.group(1)

version = match.group(2) if match.group(2) else ""

return arxiv_id + version

return None

def download_pdf(arxiv_id):

"""下载arXiv PDF文件"""

url = f"https://arxiv.org/pdf/{arxiv_id}.pdf"

try:

response = requests.get(url)

response.raise_for_status()

return io.BytesIO(response.content)

except Exception as e:

print(f"PDF下载错误: {e}")

return None

def extract_pdf_text(pdf_stream):

"""从PDF中提取文本内容"""

try:

reader = PdfReader(pdf_stream)

text = ""

for page in reader.pages:

text += page.extract_text()

return text

except Exception as e:

print(f"PDF解析错误: {e}")

return ""

def extract_pdf_metadata(pdf_stream, arxiv_id):

"""从PDF中提取元数据"""

try:

reader = PdfReader(pdf_stream)

metadata = reader.metadata

# 获取标题和作者

title = metadata.get('/Title', f"Untitled-{arxiv_id}")

authors_raw = metadata.get('/Author', "Unknown")

# 处理作者列表

authors = []

if authors_raw != "Unknown":

# 尝试分割作者(根据实际情况可能需要调整)

author_candidates = re.split(r',\s*|;\s*|\sand\s', authors_raw)

for author in author_candidates:

author = author.strip()

if author:

authors.append(author)

# 获取发布日期

publish_date = metadata.get('/CreationDate', "")

if publish_date:

# 尝试解析PDF元数据中的日期格式

match = re.search(r'D:(\d{4})(\d{2})(\d{2})', publish_date)

if match:

publish_date = f"{match.group(1)}-{match.group(2)}-{match.group(3)}"

else:

publish_date = datetime.datetime.now().strftime("%Y-%m-%d")

else:

publish_date = datetime.datetime.now().strftime("%Y-%m-%d")

return {

"title": title,

"authors": authors,

"publish_date": publish_date

}

except Exception as e:

print(f"元数据提取错误: {e}")

return {

"title": f"Untitled-{arxiv_id}",

"authors": [],

"publish_date": datetime.datetime.now().strftime("%Y-%m-%d")

}

def extract_info_with_ollama(text, query_type):

"""使用Ollama提取文章的类别、关键词、标题或作者"""

prompt = ""

if query_type == "categories":

prompt = f"""

以下是一篇学术论文的摘要,请从中提取出该论文所属的学术类别(最多10个),返回一个JSON格式的类别列表,格式为:["类别1", "类别2", ...]。

尽量使用标准的学术领域分类,如"NLP", "Computer Vision", "Machine Learning"等。

论文摘要:

{text[:10000]}

"""

elif query_type == "keywords":

prompt = f"""

以下是一篇学术论文的摘要,请从中提取出该论文的关键词(最多15个),返回一个JSON格式的关键词列表,格式为:["关键词1", "关键词2", ...]。

论文摘要:

{text[:10000]}

"""

elif query_type == "title":

prompt = f"""

你是一个精确的标题提取工具。请从以下学术论文的开头部分提取出论文的标题。

重要说明:

1. 只返回标题文本本身,不要包含任何解释、思考过程或额外内容

2. 不要使用引号或其他标点符号包裹标题

3. 不要使用"标题是:"或类似的前缀

4. 不要使用<think>或任何标记

5. 不要使用多行,只返回一行标题文本

论文内容开头:

{text[:1000]}

"""

elif query_type == "authors":

prompt = f"""

你是一个精确的作者信息提取工具。请从以下学术论文的开头部分提取出所有作者名字。

重要说明:

1. 直接返回JSON格式的作者列表,格式必须如下:["作者1", "作者2", ...]

2. 不要包含任何解释、思考过程或额外内容

3. 不要使用<think>或任何标记

4. 仅返回包含作者名字的JSON数组,不要有其他文本

论文内容开头:

{text[:1000]}

"""

try:

response = requests.post(

f"{OLLAMA_BASE_URL}/generate",

json={

"model": OLLAMA_MODEL,

"prompt": prompt,

"stream": False

}

)

response.raise_for_status()

response_data = response.json()

content = response_data.get("response", "")

# 移除可能的思维链标记

content = re.sub(r'<think>.*?</think>', '', content, flags=re.DOTALL)

content = content.strip()

# 对于标题查询,直接返回文本内容

if query_type == "title":

# 清理标题(去除多余空格、换行和引号)

title = re.sub(r'\s+', ' ', content).strip()

# 移除可能的前缀

title = re.sub(r'^(标题是[::]\s*|论文标题[::]\s*|题目[::]\s*|Title[::]*\s*)', '', title, flags=re.IGNORECASE)

# 移除可能的引号

title = re.sub(r'^["\'「『]+|["\'」』]+$', '', title)

# 限制标题长度

if len(title) > 300:

title = title[:300] + "..."

return title

# 对于作者、类别和关键词,尝试提取JSON数组

json_match = re.search(r'\[.*?\]', content, re.DOTALL)

if json_match:

try:

return json.loads(json_match.group(0))

except json.JSONDecodeError:

# 如果JSON解析失败,尝试以其他方式提取

if query_type == "authors":

# 尝试提取逗号分隔的作者

authors = [a.strip() for a in content.split(',') if a.strip()]

# 清理可能的引号

authors = [re.sub(r'^["\'「『]+|["\'」』]+$', '', a) for a in authors]

if authors:

return authors

# 如果是作者查询但无法提取JSON,尝试匹配常见的作者模式

if query_type == "authors":

# 尝试从文本中提取可能的作者名

author_lines = [line.strip() for line in content.split('\n') if line.strip()]

# 清理可能的引号和其他标记

author_lines = [re.sub(r'^["\'「『]+|["\'」』]+$', '', line) for line in author_lines]

if author_lines:

return author_lines[:5] # 限制返回最多5个作者

# 如果无法提取,返回空列表或默认值

return [] if query_type in ["categories", "keywords", "authors"] else ""

except Exception as e:

print(f"Ollama API调用错误 ({query_type}): {e}")

return [] if query_type in ["categories", "keywords", "authors"] else ""

def insert_essay_to_mongodb(collection, essay_data):

"""将论文数据插入MongoDB"""

try:

result = collection.insert_one(essay_data)

return result.inserted_id

except Exception as e:

print(f"数据库插入错误: {e}")

return None

def main():

# 连接MongoDB

collection = connect_to_mongodb()

if collection is None:

print("无法连接到MongoDB,程序退出")

return

# 获取用户输入的arXiv URL

url = input("请输入arXiv论文URL (例如: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2501.09898v4): ")

# 提取arXiv ID

arxiv_id = extract_arxiv_id(url)

if not arxiv_id:

print("无效的arXiv URL")

return

print(f"正在下载arXiv ID为 {arxiv_id} 的论文...")

# 下载PDF

pdf_stream = download_pdf(arxiv_id)

if not pdf_stream:

print("PDF下载失败")

return

# 提取文本和元数据

pdf_stream_copy = io.BytesIO(pdf_stream.getvalue()) # 创建一个副本用于提取文本

pdf_text = extract_pdf_text(pdf_stream)

metadata = extract_pdf_metadata(pdf_stream_copy, arxiv_id)

print("PDF解析完成,正在使用Ollama提取信息...")

# 检查标题是否有效,如果无效则使用大模型提取

title = metadata["title"]

if title == f"Untitled-{arxiv_id}" or not title or title.strip() == "":

print("元数据中未找到有效标题,尝试使用大模型提取...")

title = extract_info_with_ollama(pdf_text[:5000], "title")

if title:

metadata["title"] = title

# 检查作者是否有效,如果无效则使用大模型提取

authors = metadata["authors"]

if not authors:

print("元数据中未找到作者信息,尝试使用大模型提取...")

authors = extract_info_with_ollama(pdf_text[:5000], "authors")

if authors:

metadata["authors"] = authors

# 使用Ollama提取类别和关键词

categories = extract_info_with_ollama(pdf_text[:5000], "categories")

keywords = extract_info_with_ollama(pdf_text[:5000], "keywords")

# 准备要插入的数据

essay_data = {

"arxiv_id": arxiv_id,

"title": metadata["title"],

"authors": metadata["authors"],

"categories": categories,

"keywords": keywords,

"content": pdf_text,

"publish_date": metadata["publish_date"],

"insert_date": datetime.datetime.now().strftime("%Y-%m-%d %H:%M:%S")

}

# 插入数据库

inserted_id = insert_essay_to_mongodb(collection, essay_data)

if inserted_id:

print(f"论文已成功添加到数据库,ID: {inserted_id}")

print(f"标题: {metadata['title']}")

print(f"作者: {', '.join(metadata['authors'])}")

print(f"类别: {', '.join(categories)}")

print(f"关键词: {', '.join(keywords)}")

print(f"发布日期: {metadata['publish_date']}")

else:

print("论文添加失败")

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()

运行essay_database_insert_essay.py

# https://arxiv.org/pdf/2504.05299v1

# https://arxiv.org/pdf/2501.09898v4

uv run essay_database_insert_essay.py

essay_database.ai_essay.json

[{

"_id": {

"$oid": "69670233c375f34f0c97ff09"

},

"arxiv_id": "2504.05299v1",

"title": "SmolVLM: Redefining small and efficient multimodal models",

"authors": [

"Andrés Marafioti",

"Orr Zohar",

"Miquel Farré",

"Merve Noyan",

"Elie Bakouch",

"Pedro Cuenca",

"Cyril Zakka",

"Loubna Ben Allal",

"Anton Lozhkov",

"Nouamane Tazi",

"Vaibhav Srivastav",

"Joshua Lochner",

"Hugo Larcher",

"Mathieu Morlon",

"Lewis Tunstall",

"Leandro von Werra",

"Thomas Wolf"

],

"categories": [

"Computer Vision",

"Natural Language Processing",

"Machine Learning",

"Artificial Intelligence",

"Data Science",

"Software Engineering",

"Embedded Systems",

"Optimization",

"Multimedia Technology",

"Energy Efficiency"

],

"keywords": [

"SmolVLM",

"多模态模型",

"资源效率",

"GPU内存",

"推理",

"图像任务",

"视频理解",

"架构优化",

"分词策略",

"数据筛选",

"像素洗牌",

"视觉标记化",

"模型压缩",

"移动设备部署",

"边缘计算"

],