UMM01:统一多模态理解与生成模型:进展、挑战与机遇

Unified Multimodal Understanding and Generation Models: Advances, Challenges, and OpportunitiesXinjie Zhang*, JintaoGuo*, Shanshan Zhao*, Minghao Fu, Lunhao Duan, Jiakui Hu, Yong Xien Chng, Guo-Hua Wa

Unified Multimodal Understanding and Generation Models: Advances, Challenges, and Opportunities

统一多模态理解与生成模型:进展、挑战与机遇

Xinjie Zhang*, JintaoGuo*, Shanshan Zhao*, Minghao Fu, Lunhao Duan, Jiakui Hu, Yong Xien Chng, Guo-Hua Wang, Qing-Guo Chen†, Zhao Xu, Weihua Luo, Kaifu Zhang

摘要——近年来,多模态理解模型和图像生成模型都取得了显著进展。尽管各自成就斐然,这两个领域却独立演化,形成了不同的架构范式:自回归架构主导了多模态理解,而基于扩散的模型则成为图像生成的基石。近来,旨在整合这些任务的统一框架引起了越来越多的关注,GPT-4o的新能力的出现就例证了这一趋势,凸显了统一的潜力。然而,两个领域之间的架构差异也带来了重大挑战。为清晰概述当前面向统一的研究工作,我们呈现了一篇全面的综述,以指导未来研究。首先,我们介绍多模态理解与文本到图像生成模型的基础概念和最新进展。接着,我们回顾现有的统一模型,并将其分为三大架构范式:基于扩散的、基于自回归的,以及融合自回归与扩散机制的混合方法。对于每一类,我们分析了相关工作的结构设计与创新。此外,我们汇编了面向统一模型的数据集与基准测试,为未来探索提供资源。最后,我们讨论了该新兴领域面临的关键挑战,包括分词策略、跨模态注意力与数据问题。由于该领域仍处于早期阶段,我们预计会有快速发展,并将定期更新此综述。与本综述相关的参考资料可在https://github.com/AIDC-AI/Awesome-Unified-Multimodal-Models获得。

Index Terms—统一多模态模型、Multimodal understanding、图像生成、自回归模型、扩散模型

1引言

近年来,大型语言模型(LLMs)如LLaMa [1], [2], PanGu [3], [4], Qwen [5], [6], 和GPT [7], 的快速发展革新了人工智能。这些模型在规模和能力上不断扩展,推动了各类应用的突破。与此同时,LLMs已被扩展到多模态领域,催生了诸如LLaVa [8], Qwen-VL [9], [10], InternVL [11], Ovis [12], 和GPT4 [13]等强大的多模态理解模型。这些模型的能力已从简单的图像字幕生成扩展到根据用户指令执行复杂推理任务。另一方面,图像生成技术也迅速发展,出现了像

SDseries [14], [15] 和 FLUX [16] 现在能够生成与用户提示高度一致的高质量图像。

用于LLMs和多模态理解模型的主流架构范式是自回归生成[17],它依赖仅解码器结构和基于下一个代币预测的顺序文本生成。相比之下,文本到图像生成领域沿着不同的轨迹演进。最初由生成对抗网络(GANs)主导[18],图像生成随后转向了基于扩散的模型[19],这些模型利用诸如UNet [14]和DiT [20],[21]之类的架构,同时配合像CLIP [22]和T5 [23]这样的先进文本编码器。尽管在使用受LLM启发的架构进行图像生成方面有一些探索

[24], [25], [26],,但基于扩散的方法目前在性能上仍然是最先进的。

尽管在图像生成质量方面,自回归模型落后于基于扩散的方法,但它们与大语言模型在结构上的一致性使其在开发统一多模态系统时特别具有吸引力。能够同时理解和生成多模态内容的统一模型具有巨大的潜力:它可以根据复杂指令生成图像、对视觉数据进行推理,并通过生成的输出可视化多模态分析。GPT-4o在2025年3月[27]所展现的增强能力进一步凸显了这一潜力,并在统一化方向上引发了广泛关注。

Unified Multimodal Understanding and Generation Models: Advances, Challenges, and Opportunities

Xinjie Zhang*, Jintao Guo*, Shanshan Zhao*, Minghao Fu, Lunhao Duan, Jiakui Hu, Yong Xien Chng, Guo-Hua Wang, Qing-Guo Chen†, Zhao Xu, Weihua Luo, Kaifu Zhang

Abstract—Recent years have seen remarkable progress in both multimodal understanding models and image generation models. Despite their respective successes, these two domains have evolved independently, leading to distinct architectural paradigms: While autoregressive-based architectures have dominated multimodal understanding, diffusion-based models have become the cornerstone of image generation. Recently, there has been growing interest in developing unified frameworks that integrate these tasks. The emergence of GPT-4o’s new capabilities exemplifies this trend, highlighting the potential for unification. However, the architectural differences between the two domains pose significant challenges. To provide a clear overview of current efforts toward unification, we present a comprehensive survey aimed at guiding future research. First, we introduce the foundational concepts and recent advancements in multimodal understanding and text-to-image generation models. Next, we review existing unified models, categorizing them into three main architectural paradigms: diffusion-based, autoregressive-based, and hybrid approaches that fuse autoregressive and diffusion mechanisms. For each category, we analyze the structural designs and innovations introduced by related works. Additionally, we compile datasets and benchmarks tailored for unified models, offering resources for future exploration. Finally, we discuss the key challenges facing this nascent field, including tokenization strategy, cross-modal attention, and data. As this area is still in its early stages, we anticipate rapid advancements and will regularly update this survey. Our goal is to inspire further research and provide a valuable reference for the community. The references associated with this survey are available on https://github.com/AIDC-AI/Awesome-Unified-Multimodal-Models

Index Terms—Unified multimodal models, Multimodal understanding, Image generation, Autoregressive model, Diffusion model

1 INTRODUCTION

In recent years, the rapid advancement of large language models (LLMs), such as LLaMa [1], [2], PanGu [3], [4], Qwen [5], [6], and GPT [7], has revolutionized artificial intelligence. These models have scaled up in both size and capability, enabling breakthroughs across diverse applications. Alongside this progress, LLMs have been extended into multimodal domains, giving rise to powerful multimodal understanding models like LLaVa [8], Qwen-VL [9], [10], InternVL [11], Ovis [12], and GPT4 [13]. These models have expanded their capabilities beyond simple image captioning to performing complex reasoning tasks based on user instructions. On the other hand, image generation technology has also experienced rapid development, with models like

SD series [14], [15] and FLUX [16] now capable of producing high-quality images that adhere closely to user prompts.

The predominant architectural paradigm for LLMs and multimodal understanding models is autoregressive generation [17], which relies on decoder-only structures and next-token prediction for sequential text generation. In contrast, the field of text-to-image generation has evolved along a different trajectory. Initially dominated by Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) [18], image generation has since transitioned to diffusion-based models [19], which leverage architectures like UNet [14] and DiT [20], [21] alongside advanced text encoders such as CLIP [22] and T5 [23]. Despite some explorations into using LLM-inspired architectures for image generation [24], [25], [26], diffusion-based approaches remain the state-of-the-art in terms of performance currently.

While autoregressive models lag behind diffusion-based methods in image generation quality, their structural consistency with LLMs makes them particularly appealing for developing unified multimodal systems. A unified model capable of both understanding and generating multimodal content holds immense potential: it could generate images based on complex instructions, reason about visual data, and visualize multimodal analyses through generated outputs. The unveiling of GPT-4o’s enhanced capabilities [27] in March 2025 has further highlighted this potential, sparking widespread interest in unification.

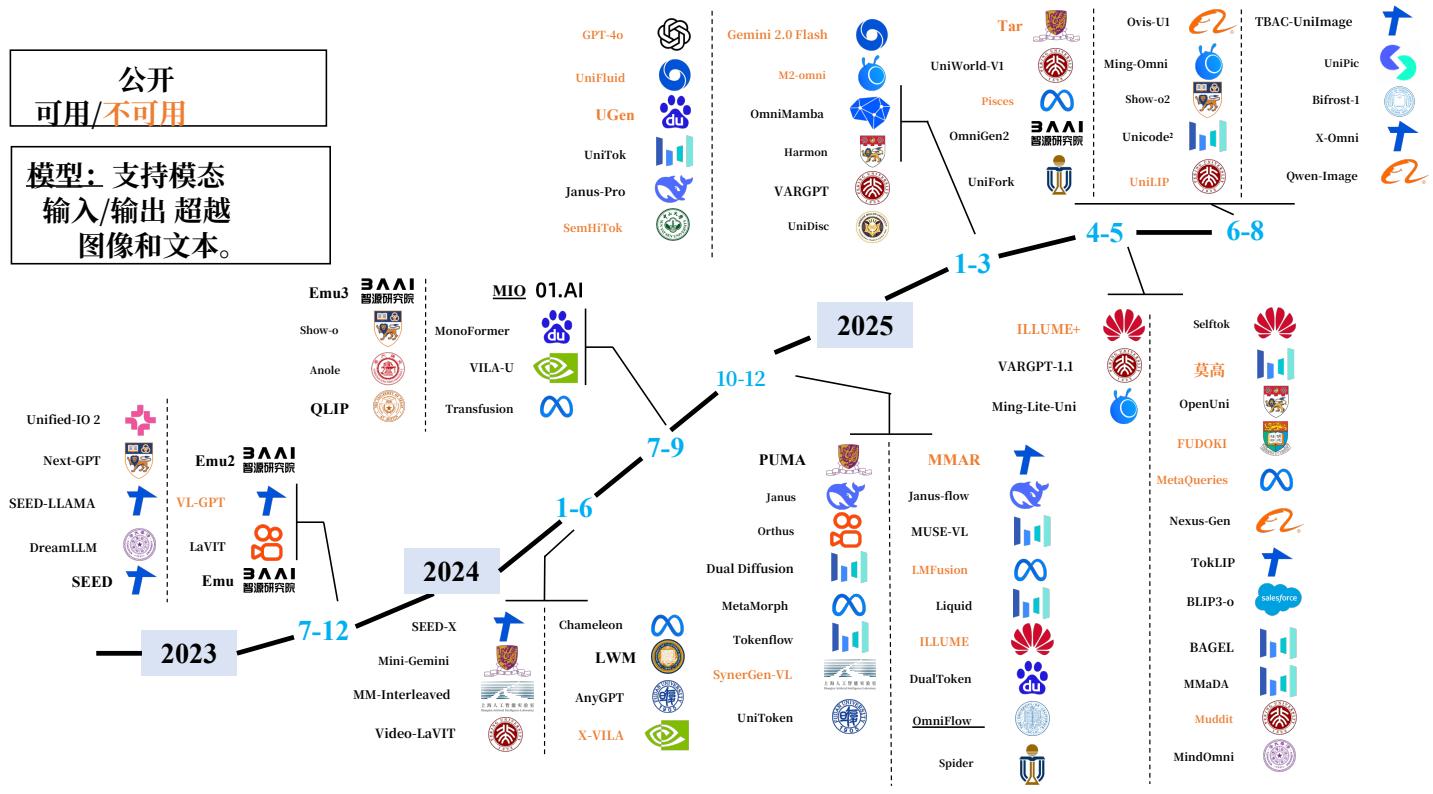

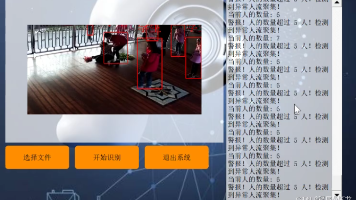

图1.公开可用和不可用的统一多模态模型时间线。图中模型按发布年份分类,涵盖2023年至2025年。图中带下划线的模型代表任意到任意多模态模型,能够处理超出文本和图像的输入或输出,如音频、视频和语音。该时间线突出了该领域的快速增长。

然而,设计这样一个统一的框架面临重大挑战。它需要将自回归模型在推理和文本生成方面的优势与基于扩散的模型在高质量图像合成方面的鲁棒性相结合。仍有一些关键问题尚未解决,包括如何有效地对图像进行分词以用于自回归生成。一些方法 [28], [29], [30] 采用在扩散管道中常用的 VAE [31] 或 VQ-GAN [32] 或其相关变体,而其他方法 [33], [34], [35] 则使用诸如 EVA-CLIP [36] 和 OpenAI-CLIP [22] 之类的语义编码器。此外,尽管离散令牌是自回归模型中文本的标准表示,emerging research [25] 表明连续表示可能更适合图像令牌。除了分词之外,将并行扩散策略与序列化自回归生成相结合的混合架构 [37], [38], [39],相较于简单双纯的自回归架构,提供了另一条有前景的途径。因此,对于统一多模态模型而言,图像分词技术和架构设计仍处于初期阶段。

为了全面概述统一多模态模型的现状(如图1所示),并为未来的研究工作提供参考,我们撰写了这篇综述。首先介绍多模态理解和图像生成的基础概念与最新进展,涵盖基于自回归和基于扩散的范式。接着回顾现有的统一模型,并将它们归类为三种主要的架构范式:基于扩散的、基于自回归的,以及融合自回归与扩散机制的混合方法,

在自回归和混合类别中,我们进一步根据模型的图像标记化策略对其进行分类,以反映该领域中方法的多样性。

除了架构之外,我们还汇编了为训练和评估统一多模态模型量身定制的数据集和基准。这些资源涵盖多模态理解、文本到图像生成、图像编辑及其他相关任务,为未来的探索提供了基础。最后,我们讨论了这一新兴领域面临的关键挑战,包括高效的分词策略、数据构建、模型评估等。应对这些挑战对提升统一多模态模型的能力和可扩展性至关重要。

在社区中,已有关于大型语言模型[40],[41],多模态理解[42],[43],[44],和图像生成[45],[46],的优秀综述,而我们的工作专注于理解与生成任务的整合。建议读者参考这些互补的综述以获得相关主题的更广阔视角。我们旨在激发该快速发展领域的更多研究,并为社区提供有价值的参考。包括相关参考文献、数据集和与本综述相关的基准测试在内的资料已在GitHub上提供,并将定期更新以反映持续的进展。

Fig. 1. Timeline of Publicly Available and Unavailable Unified Multimodal Models. The models are categorized by their release years, from 2023 to 2025. Models underlined in the diagram represent any-to-any multimodal models, capable of handling inputs or outputs beyond text and image, such as audio, video, and speech. The timeline highlights the rapid growth in this field.

However, designing such a unified framework presents significant challenges. It requires integrating the strengths of autoregressive models for reasoning and text generation with the robustness of diffusion-based models for high-quality image synthesis. Key questions remain unresolved, including how to tokenize images effectively for autoregressive generation. Some approaches [28], [29], [30] employ VAE [31] or VQ-GAN [32] commonly used in diffusion-based pipelines, or relevant variants, while others [33], [34], [35] utilize semantic encoders like EVA-CLIP [36] and OpenAI-CLIP [22]. Additionally, while discrete tokens are standard for text in autoregressive models, continuous representations may be more suitable for image tokens, as suggested by emerging research [25]. Beyond tokenization, hybrid architectures [37], [38], [39] that combine parallel diffusion strategies with sequential autoregressive generation offer another promising approach aside from naive autoregressive architecture. Thus, both image tokenization techniques and architectural designs remain in their nascent stages for unified multimodal models.

To provide a comprehensive overview of the current state of unified multimodal models (as illustrated in Fig. 1), thereby benefiting future research endeavors, we present this survey. We begin by introducing the foundational concepts and recent advancements in both multimodal understanding and image generation, covering both autoregressive and diffusion-based paradigms. Next, we review existing unified models, categorizing them into three main architectural paradigms: diffusion-based, autoregressive-based, and hybrid approaches that fuse autoregressive and diffu

sion mechanisms. Within the autoregressive and hybrid categories, we further classify models based on their image tokenization strategies, reflecting the diversity of approaches in this area.

Beyond architecture, we assemble datasets and benchmarks tailored for training and evaluating unified multimodal models. These resources span multimodal understanding, text-to-image generation, image editing, and other relevant tasks, providing a foundation for future exploration. Finally, we discuss the key challenges facing this nascent field, including efficient tokenization strategy, data construction, model evaluation, etc. Tackling these challenges will be crucial for advancing the capabilities and scalability of unified multimodal models.

In the community, there exist excellent surveys on large language models [40], [41], multimodal understanding [42], [43], [44], and image generation [45], [46], while our work focuses specifically on the integration of understanding and generation tasks. Readers are encouraged to consult these complementary surveys for a broader perspective on related topics. We aim to inspire further research in this rapidly evolving field and provide a valuable reference for the community. Materials including relevant references, datasets, and benchmarks associated with this survey are available on GitHub and will be regularly updated to reflect ongoing advancements.

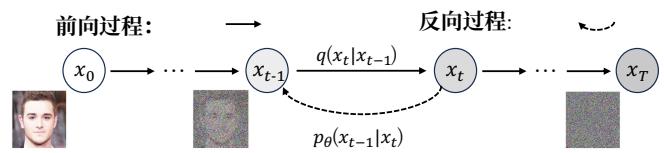

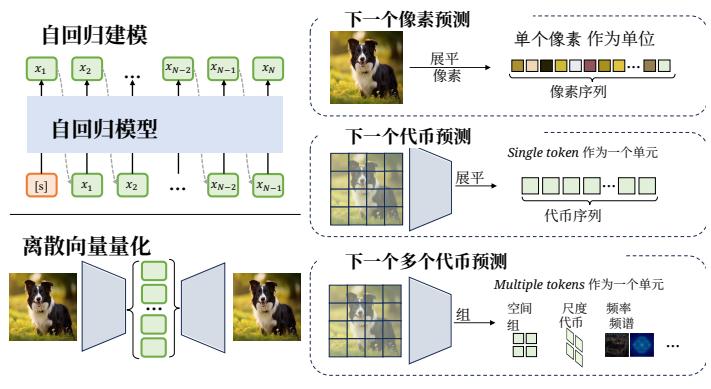

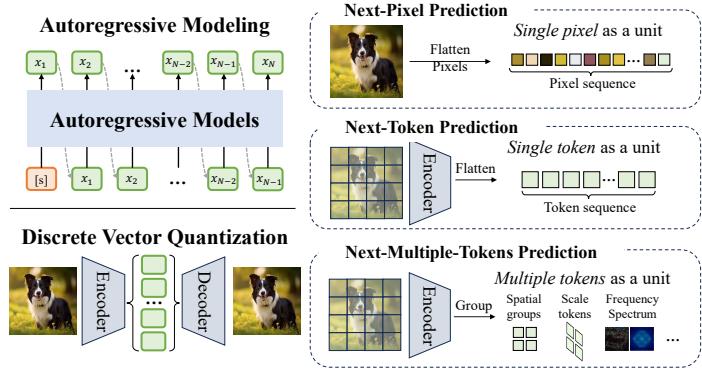

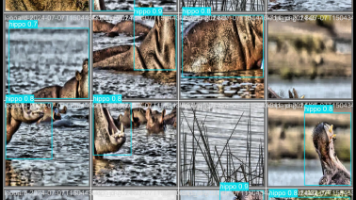

图4.自回归模型核心组件示意图,包括自回归序列建模和离散向量量化。现有自回归模型大致可分为三类:下一个像素预测将图像展平为像素序列;下一个代币预测通过视觉分词器将图像转换为代币序列;下一个多个代币预测在自回归步骤中输出多个代币。

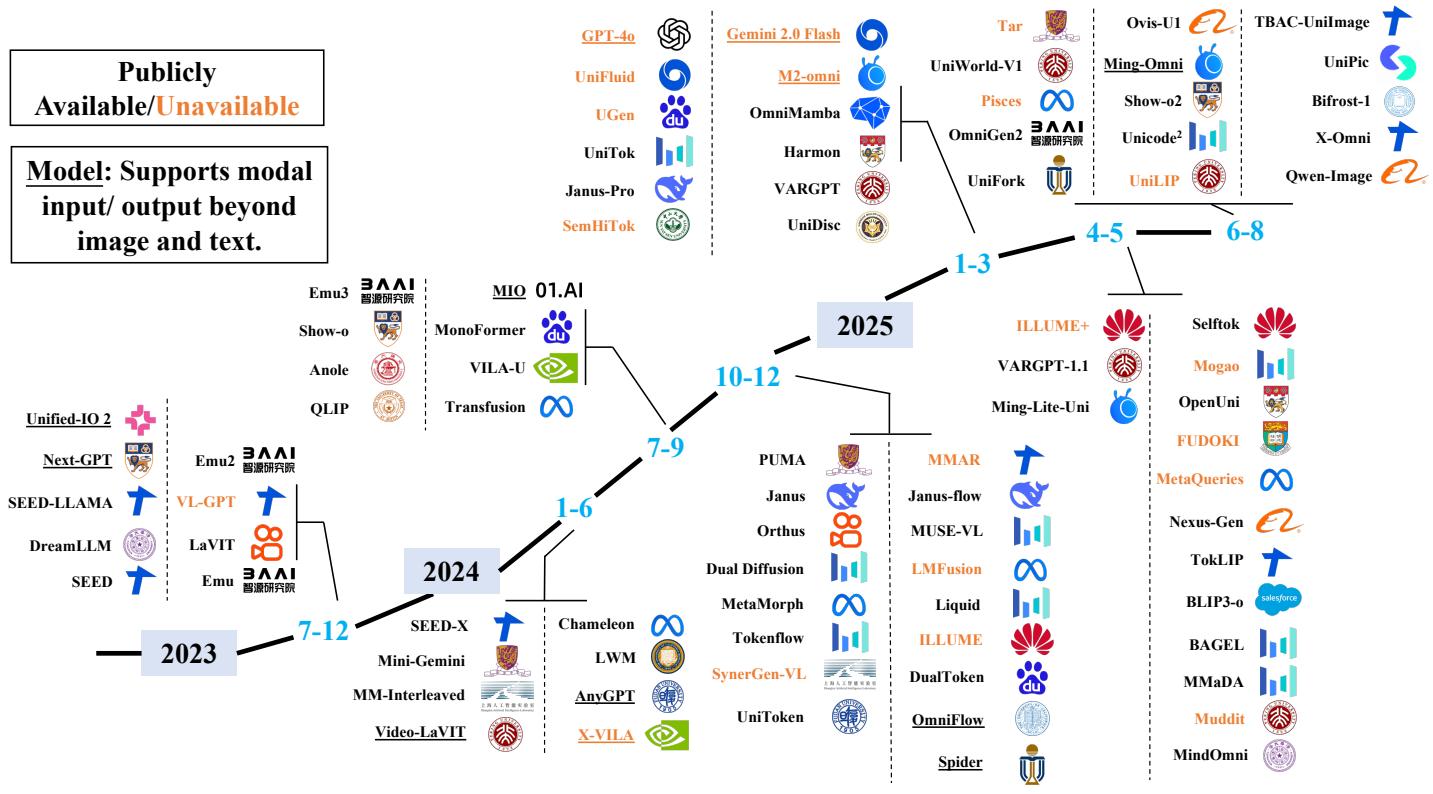

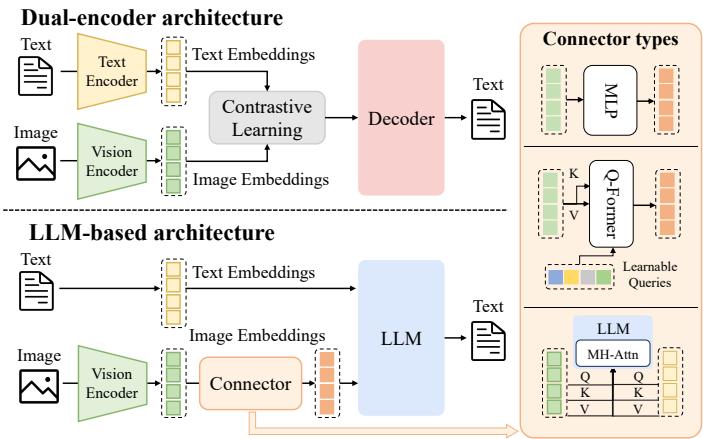

图2. 多模态理解模型的架构,包含多模态编码器、一个连接器和一个大语言模型。多模态编码器将图像、音频或视频转换为特征,这些特征由连接器处理作为大语言模型的输入。连接器的架构大致可分为三类:基于投影的、基于查询的和基于融合的连接器。

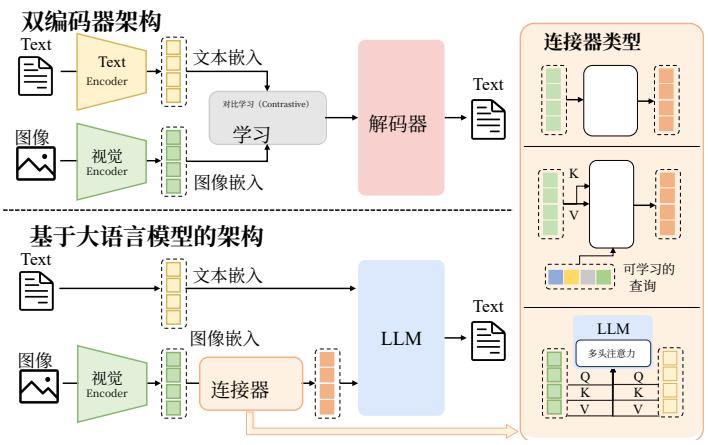

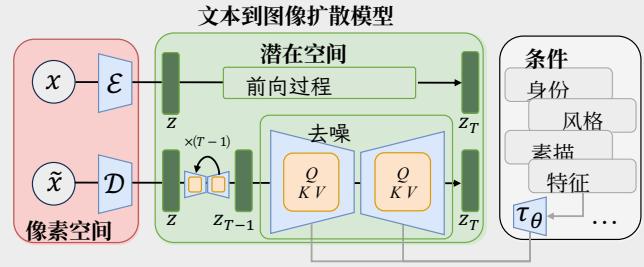

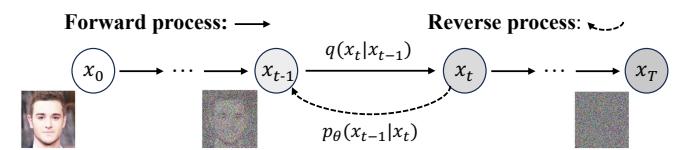

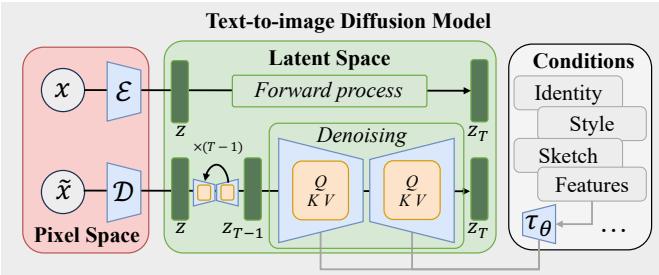

图3.基于扩散的文本到图像生成模型示意图,展示了除了文本之外的多种条件如何被引入以引导生成结果。图像生成被表述为一对马尔可夫链:正向过程通过加入高斯噪声逐步破坏输入数据,反向过程则学习一个参数化分布以迭代去噪,恢复到输入数据。

2 预备知识

2.1多模态理解模型

多模态理解模型是指能够接收、多模态输入上进行推理并生成输出的基于LLM的架构[47]。这些模型将LLM的生成和推理能力扩展到文本数据之外,使得在多样信息模态间实现丰富的语义理解成为可能[42],[48]。现有方法的大部分工作集中于视觉-语言理解(VLU),它将视觉(例如,图像和视频)与文本输入整合,以支持对空间关系、对象、场景和抽象概念的更全面理解[49],[50],[51]。多模态理解模型的典型架构示于图2。这些模型在混合输入空间内运行,其中文本数据以离散形式表示,而视觉信号被编码为连续表示[52]。类似

与传统大语言模型类似,它们的输出作为从内部表示派生的离散代币生成,使用基于分类的语言建模和任务特定的解码策略 [8], [53]。

早期的视觉-语言理解模型主要集中在使用双编码器架构对视觉和文本模态进行对齐,其中图像和文本首先分别编码,然后通过对齐的潜在表示联合推理,包括CLIP [22]、ViLBERT [54]、VisualBERT [55],和UNITER [56]。尽管这些开创性模型为多模态推理奠定了关键原则,但它们高度依赖基于区域的视觉预处理和独立编码器,限制了模型的可扩展性和通用性。随着强大大语言模型的出现,视觉-语言理解模型已逐步转向仅解码器架构,结合被冻结或仅微调的LLM主干。这些方法主要通过具有不同结构的连接器转换图像嵌入,如图2所示。具体来说,MiniGPT-4 [57]使用单层可学习层将来自CLIP的图像嵌入投射到Vicuna[58]的代币空间;BLIP-2 [53]引入了一个查询变换器,将冻结的视觉编码器与冻结的LLM(例如Flan-T5[59]或Vicuna[58])连接起来,从而以显著更少的可训练参数实现高效的视觉-语言对齐;Flamingo[60]则采用门控交叉注意力层,将预训练的视觉编码器与冻结的Chinchilla[61]解码器连接。

近年来在视觉语言理解(VLU)方面的进展凸显了向通用多模态理解的转变。GPT-4V [62] 将GPT-4框架 [13] 扩展到分析用户提供的图像输入,尽管为专有模型,但在视觉推理、图像描述和多模态对话方面表现出强大能力。

Gemini [63], 基于仅解码器架构,支持图像、视频和音频模态,其Ultra版本在多模态推理任务上树立了新的基准。

Qwen系列体现了可扩展的多模态设计:Qwen-VL [5]引入了视觉感受器和对齐模块,而Qwen2-VL [9]增加了动态分辨率处理和M-RoPE,以稳健地处理多样化输入。

LLaVA-1.5 [64]和LLaVA-

Fig. 4. Illustration of core components in autoregressive models, including the autoregression sequence modeling and discrete vector quantization. Exiting autoregressive models can be roughly divided into three types: Next-Pixel Prediction flattens the image into a pixel sequence, Next-Token Prediction converts the image into a token sequence via a visual tokenizer, and Next-Multiple-Token Prediction outputs multiple tokens in an autoregressive step.

Fig. 2. Architecture of multimodal understanding models, containing multimodal encoders, a connector, and a LLM. The multimodal encoders transform images, audio, or videos into features, which are processed by the connector as the input of LLM. The architectures of theconnector can be broadly categorized by three types: projection-based, query-based, and fusion-based connectors.

Fig. 3. Illustration of diffusion-based text-to-image generation models, where various conditions beyond text are introduced to steer the outcomes. The image generation is formulated as a pair of Markov chains: a forward process that gradually corrupts input data by adding Gaussian noise, and a reverse process that learns a parameterized distribution to iteratively denoise back to the input data.

2 PRELIMINARY

2.1 Multimodal Understanding Model

Multimodal understanding models refer to LLM-based architectures capable of receiving, reasoning over, and generating outputs from multimodal inputs [47]. These models extend the generative and reasoning capabilities of LLMs beyond textual data, enabling rich semantic understanding across diverse information modalities [42], [48]. Most efforts of existing methods focus on vision-language understanding (VLU), which integrates both visual (e.g., images and videos) and textual inputs to support a more comprehensive understanding of spatial relationships, objects, scenes, and abstract concepts [49], [50], [51]. A typical architecture of multimodal understanding models is illustrated in Fig. 2. These models operate within a hybrid input space, where textual data are represented discretely, while visual signals are encoded as continuous representations [52]. Similar

to traditional LLMs, their outputs are generated as discrete tokens derived from internal representations, using classification-based language modeling and task-specific decoding strategies [8], [53].

Early VLU models primarily focused on aligning visual and textual modalities using dual-encoder architectures, wherein images and text are first encoded separately and then jointly reasoned over via aligned latent representations, including CLIP [22], ViLBERT [54], VisualBERT [55], and UNITER [56]. Although these pioneering models established key principles for multimodal reasoning, they depended heavily on region-based visual preprocessing and separate encoders, limiting the scalability and generality of the mode. With the emergence of powerful LLMs, VLU models have progressively shifted toward decoder-only architectures that incorporate frozen or minimally fine-tuned LLM backbones. These methods primarily transform image embeddings through a connector with different structures, as illustrated in Fig. 2. Specifically, MiniGPT-4 [57] utilized a single learnable layer to project CLIP-derived image embeddings into the token space of Vicuna [58]. BLIP-2 [53] introduced a querying transformer, to bridge a frozen visual encoder with a frozen LLM (e.g., Flan-T5 [59] or Vicuna [58]), enabling efficient vision-language alignment with significantly fewer trainable parameters. Flamingo [60] employed gated cross-attention layers to connect a pretrained vision encoder with a frozen Chinchilla [61] decoder.

Recent advances in VLU highlight a shift toward general multimodal understanding. GPT-4V [62] extends the GPT-4 framework [13] to analyze image inputs provided by the user, demonstrating strong capabilities in visual reasoning, captioning, and multimodal dialogue, despite its proprietary nature. Gemini [63], built upon a decoder-only architecture, supports image, video, and audio modalities, with its Ultra variant setting new benchmarks in multimodal reasoning tasks. The Qwen series exemplifies scalable multimodal design: Qwen-VL [5] incorporates visual receptors and grounding modules, while Qwen2-VL [9] adds dynamic resolution handling and M-RoPE for robust processing of varied inputs. LLaVA-1.5 [64] and LLaVA

Next [65] 使用基于CLIP的视觉编码器和Vicuna风格的LLMs,在VQA和遵循指令任务中具有竞争力。InternVL系列 [11], [66], [67] 探索了统一的多模态预训练策略,能够同时从文本和视觉数据中学习,以提升各类视觉-语言任务的性能。Ovis [12]通过一个可学习的视觉嵌入查找表引入了结构嵌入对齐机制,从而生成在结构上与文本代币相映射的视觉嵌入。最近,一些模型开始探索用于多模态处理的可扩展且统一的架构。DeepSeek-VL2 [68] 采用专家混合架构(MoE)来增强跨模态推理。总体而言,这些模型清晰地推动了面向指令微调和以代币为中心的框架发展,使其能够以统一且可扩展的方式应对多样的多模态任务。

2.2 文本到图像模型

扩散模型。扩散模型(DM)将生成表述为一对马尔可夫链:前向过程通过在时间步上逐步加入高斯噪声来逐渐破坏数据 x 0 x_0 x0 T T T 以生成 x T x_{T} xT ,以及反向过程学习一个参数化分布以迭代去噪回到数据流形[19],[69],[70]。形式上,如图3所示,在前向过程中,给定数据分布 x 0 ∼ q ( x 0 ) x_0\sim q(x_0) x0∼q(x0) ,在每个步骤 t t t 数据 x t x_{t} xt 被噪声化:

q ( x 1 : T ∣ x 0 ) : = ∏ T q ( x t ∣ x t − 1 ) , (1) q \left(x _ {1: T} \mid x _ {0}\right) := \prod^ {T} q \left(x _ {t} \mid x _ {t - 1}\right), \tag {1} q(x1:T∣x0):=∏Tq(xt∣xt−1),(1)

q ( t x ∣ x − t − 1 ) = N x ( t 1 − ; β t − t − 1 1 , β t ) 1 t = 1 , ( x − ) 2 q \left(\underset {x} {t} \mid x _ {-} ^ {t - 1}\right) = \underset {x} {\mathcal {N}} (\underset {1 -} {t}; \sqrt [ t = 1 ]{\frac {\beta_ {t - t - 1} ^ {1} , \beta_ {t})}{1}}, \underset {x _ {-}} () \quad 2 q(xt∣x−t−1)=xN(1−t;t=11βt−t−11,βt),x−()2

其中 β t \beta_{t} βt 是噪声的方差超参数。在反向过程中,模型逐步去噪以逼近马尔可夫链的反向。逆转移 p θ ( x t − 1 ∣ x t ) p_{\theta}(x_{t - 1}|x_t) pθ(xt−1∣xt) 被参数化为:

p θ ( x t − 1 ∣ x t ) = N ( x t − 1 ; μ θ ( x t , t ) , Σ θ ( x t , t ) ) , (3) p _ {\theta} \left(x _ {t - 1} \mid x _ {t}\right) = \mathcal {N} \left(x _ {t - 1}; \mu_ {\theta} \left(x _ {t}, t\right), \Sigma_ {\theta} \left(x _ {t}, t\right)\right), \tag {3} pθ(xt−1∣xt)=N(xt−1;μθ(xt,t),Σθ(xt,t)),(3)

网络对均值 μ θ ( x t , t ) \mu_{\theta}(x_t,t) μθ(xt,t) 和方差 Σ θ ( x t , t ) \Sigma_{\theta}(x_t,t) Σθ(xt,t) 进行参数化。网络以被加噪的数据 x t x_{t} xt 和时间步 t t t 作为输入,输出用于噪声预测的正态分布参数。噪声向量由采样 x T ∼ p ( x T ) x_{T} \sim p(x_{T}) xT∼p(xT) 初始化,然后从学习到的转移核 x t − 1 ∼ p θ ( x t − 1 ∣ x t ) x_{t - 1} \sim p_{\theta}(x_{t - 1}|x_{t}) xt−1∼pθ(xt−1∣xt) 逐步采样,直到 t = 1 t = 1 t=1 。训练目标是最小化负对数似然的变分下界:

L = E q ( x 0 , x 1 : T ) [ ∥ ϵ θ ( x t , t ) − ϵ ∗ ( x t , t ) ∥ 2 ] \mathcal{L} = \mathbb{E}_{q(x_0,x_{1:T})}\left[\| \epsilon_\theta (x_t,t) - \epsilon^* (x_t,t)\| ^2\right] L=Eq(x0,x1:T)[∥ϵθ(xt,t)−ϵ∗(xt,t)∥2] , 其中 ϵ θ ( x t , t ) \epsilon_{\theta}(x_{t},t) ϵθ(xt,t) 是模型对时间步 t t t 时噪声的预测, ϵ ∗ ( x t , t ) \epsilon^{*}(x_{t},t) ϵ∗(xt,t) 是在该时间步加入的真实噪声。

早期的扩散模型使用基于U-Net的架构来近似得分函数[19]。基于Wide ResNet的U-Net设计集成了残差连接和自注意力块,以保持梯度流并恢复精细的图像细节。这些方法大致可分为像素级方法和潜在特征级方法。像素级方法直接在像素空间中运行扩散过程,包括引入“无分类器引导”的GLIDE[71]和采用预训练大型语言模型作为文本编码器的Imagen[72],即T5-XXL。然而,这些方法在训练和推理上计算成本昂贵,导致

催生了在预训练变分自编码器潜在空间中运行的潜在扩散模型(LDMs)[14]的发展。LDMs在保持高生成质量的同时实现了计算效率,从而激发了各种基于扩散的生成模型的发展,包括VQ-Diffusion[73],、SD2.0[74],、SDXL[75],和UPainting[76]。

在Transformer架构的进步推动下,基于Transformer的模型已被引入到扩散过程中。开创性的Diffusion Transformers (DiT) [20]将输入图像转换为一系列图像补丁序列,并通过一系列Transformer模块处理这些序列。DiT还将扩散时间步 t t t 和条件信号 c c c 等额外的条件信息作为输入。DiT的成功激发了许多先进的生成方法的出现,包括在扩散训练中注入自监督视觉表征以增强大规模性能的REPA [77],SD3.0 [15]使用两个独立的权重集合来建模文本和图像模态,以及其他方法[78],[79],[80]。在文本编码器方面,这些方法主要利用对比学习将图像和文本模态对齐到共享的潜在空间,联合在大规模图像-字幕对上训练独立的图像和文本编码器[22],[53],[81]。具体而言,GLIDE [71]同时探索了CLIP引导和无分类器引导,证明了基于CLIP的扩散优于早期的GAN基线并支持强大的文本驱动编辑。SD[14]采用了冻结的CLIP-ViT-L/14编码器来为其潜在扩散去噪器提供条件,从而以高效计算实现高质量样本。SD3.0 [15]使用CLIP ViT-L/14、OpenCLIPbigG/14和T5-v1.1 XXL将文本转换为用于生成引导的嵌入表示。

最近在扩散模型方面的进展已将LLMs引入以增强文本到图像的扩散生成[82],[83],这显著提升了文本-图像对齐性以及生成图像的质量。RPG[83]利用多模态LLMs的视觉语言先验,从文本提示中推理出互补的空间布局,并在文本引导的图像生成和编辑过程中操控扩散模型的对象组成。然而,这些方法针对特定任务需要不同的模型架构、训练策略和参数配置,给模型管理带来了挑战。一种更具可扩展性的解决方案是采用一个unified generation model,能够处理多种数据生成任务[84],[85],[86],[87]。OmniGen[84]实现了文本到图像的生成功能,并支持各种下游任务,如图像编辑、主体驱动生成和视觉条件生成。UniReal[85]将图像级任务视为不连续的视频生成,将不同数量的输入和输出图像视为帧,从而无缝支持图像生成、编辑、定制和合成等任务。GenArtist[86]提供了一个由多模态大型语言模型(MLLM)代理协调的统一图像生成与编辑系统。UniVG[87]将多模态输入视为统一条件,并通过一组权重来支持各种下游应用。随着该领域研究的推进,预计会出现越来越多的统一模型,能够处理更广泛的图像生成与编辑任务。

Next [65] use CLIP-based vision encoders and Vicuna-style LLMs for competitive performance in VQA and instruction-following tasks. The InternVL series [11], [66], [67] explore a unified multimodal pre-training strategy, which simultaneously learns from both text and visual data to enhance performance across various visual-linguistic tasks. Ovis [12] introduces a structural embedding alignment mechanism through a learnable visual embedding lookup table, thus producing visual embeddings that structurally mirror textual tokens. Recently, some models have explored scalable and unified architectures for multimodal processing. DeepSeek-VL2 [68] employs a Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) architecture to enhance cross-modal reasoning. Overall, these models mark a clear progression toward instruction-tuned and token-centric frameworks capable of addressing diverse multimodal tasks in a unified and scalable manner.

2.2 Text-to-Image Model

Diffusion models. Diffusion models (DM) formulate generation as a pair of Markov chains: a forward process that gradually corrupts data x 0 x_0 x0 by adding Gaussian noise over T T T timesteps to produce x T x_{T} xT , and a reverse process that learns a parameterized distribution to iteratively denoise back to the data manifold [19], [69], [70]. Formally, as shown in Fig. 3 in the forward process, given the date distribution x 0 ∼ q ( x 0 ) x_0 \sim q(x_0) x0∼q(x0) , at each step t t t , the data x t x_{t} xt is noised:

q ( x 1 : T ∣ x 0 ) : = ∏ t = 1 T q ( x t ∣ x t − 1 ) , (1) q \left(x _ {1: T} \mid x _ {0}\right) := \prod_ {t = 1} ^ {T} q \left(x _ {t} \mid x _ {t - 1}\right), \tag {1} q(x1:T∣x0):=t=1∏Tq(xt∣xt−1),(1)

q ( x t ∣ x t − 1 ) = N ( x t ; 1 − β t x t − 1 , β t I ) , (2) q \left(x _ {t} \mid x _ {t - 1}\right) = \mathcal {N} \left(x _ {t}; \sqrt {1 - \beta_ {t}} x _ {t - 1}, \beta_ {t} \mathbf {I}\right), \tag {2} q(xt∣xt−1)=N(xt;1−βtxt−1,βtI),(2)

where β t \beta_{t} βt is the variance hyperparameters of the noise. During the reverse process, the model progressively denoises the data to approximate the reverse of the Markov chain. The reverse transition p θ ( x t − 1 ∣ x t ) p_{\theta}(x_{t - 1}|x_t) pθ(xt−1∣xt) is parameterized as:

p θ ( x t − 1 ∣ x t ) = N ( x t − 1 ; μ θ ( x t , t ) , Σ θ ( x t , t ) ) , (3) p _ {\theta} \left(x _ {t - 1} \mid x _ {t}\right) = \mathcal {N} \left(x _ {t - 1}; \mu_ {\theta} \left(x _ {t}, t\right), \Sigma_ {\theta} \left(x _ {t}, t\right)\right), \tag {3} pθ(xt−1∣xt)=N(xt−1;μθ(xt,t),Σθ(xt,t)),(3)

where the network parameterizes the mean μ θ ( x t , t ) \mu_{\theta}(x_t,t) μθ(xt,t) and variance Σ θ ( x t , t ) \Sigma_{\theta}(x_t,t) Σθ(xt,t) . The network takes the noised data x t x_{t} xt and time step t t t as inputs, and outputs the parameters of the normal distribution for noise prediction. The noise vector is initiated by sampling x T ∼ p ( x T ) x_{T} \sim p(x_{T}) xT∼p(xT) , and then successively sample from the learned transition kernels x t − 1 ∼ p θ ( x t − 1 ∣ x t ) x_{t-1} \sim p_{\theta}(x_{t-1}|x_{t}) xt−1∼pθ(xt−1∣xt) until t = 1 t = 1 t=1 . The training objective is to minimize a Variational Lower-Bound of the Negative Log-Likelihood: L = E q ( x 0 , x 1 : T ) [ ∥ ϵ θ ( x t , t ) − ϵ ∗ ( x t , t ) ∥ 2 ] \mathcal{L} = \mathbb{E}_{q(x_0,x_1:T)}\left[\| \epsilon_{\theta}(x_t,t) - \epsilon^* (x_t,t)\| ^2\right] L=Eq(x0,x1:T)[∥ϵθ(xt,t)−ϵ∗(xt,t)∥2] , where ϵ θ ( x t , t ) \epsilon_{\theta}(x_t,t) ϵθ(xt,t) is the model’s prediction of the noise at timestep t t t , and ϵ ∗ ( x t , t ) \epsilon^{*}(x_{t},t) ϵ∗(xt,t) is the true noise added at that timestep.

Early diffusion models utilized a U-Net architecture to approximate the score function [19]. The U-Net design, based on a Wide ResNet, integrates residual connections and self-attention blocks to preserve gradient flow and recover fine-grained image details. These methods could be roughly divided into pixel-level methods and latent-feature-level methods. The pixel-level methods directly operate the diffusion process in the pixel space, including GLIDE [71] that introduced “classifier-free guidance” and Imagen [72] that employ the pretrained large language model, i.e., T5-XXL [23], as text encoder. However, these methods suffer expensive raining and inference computation costs, leading

to the development of Latent Diffusion Models (LDMs) [14] that operate in the latent space of a pre-trained variational autoencoder. LDMs achieve computational efficiency while preserving high-generation quality, thus inspiring various diffusion-based generative models, including VQ-Diffusion [73], SD 2.0 [74], SD XL [75], and UPainting [76].

Advancements in transformer architectures have led to the adoption of transformer-based models in diffusion processes. The pioneering Diffusion Transformers (DiT) [20] transforms input images into a sequence of patches and feeds them through a series of transformer blocks. DiT takes additional conditional information such as the diffusion timestep t t t and a conditioning signal c c c as inputs. The success of DiT inspired many advanced generative methods, including REPA [77] that injects self-supervised visual representations into diffusion training to strengthen large-scale performance, SD 3.0 [15] use two separate sets of weights to model text and image modality, and others [78], [79], [80]. For text encoders, these methods primarily use utilized contrastive learning to align image and text modalities in a shared latent space, which jointly trained separate image and text encoders on large-scale image-caption pairs [22], [53], [81]. Specifically, GLIDE [71] explores both CLIP guidance and classifier-free guidance, demonstrating that CLIP-conditioned diffusion outperforms earlier GAN baselines and supports powerful text-driven editing. SD [14] employs a frozen CLIP-ViT-L/14 encoder to condition its latent diffusion denoiser, achieving high-quality samples with efficient computation. SD 3.0 [15] utilizes CLIP ViT-L/14, OpenCLIP bigG/14, and T5-v1.1 XXL to transform text into embeddings for generation guidance.

Recent advancements in diffusion models have incorporated LLMs to enhance text-to-image diffusion generation [82], [83], which significantly improves the text-image alignment as well as the quality of generated images. RPG [83] leverages the vision-language prior of multimodal LLMs to reason out complementary spatial layouts from text prompts, and manipulates the object compositions for diffusion models in both text-guided image generation and editing process. However, these methods require different model architectures, training strategies, and parameter configurations for specific tasks, which presents challenges in managing these models. A more scalable solution is to adopt a unified generation model capable of handling a variety of data generation tasks [84], [85], [86], [87]. OmniGen [84] achieves text-to-image generation capabilities and supports various downstream tasks, such as image editing, subject-driven generation, and visual-conditional generation. UniReal [85] treats image-level tasks as discontinuous video generation, treating varying numbers of input and output images as frames, enabling seamless support for tasks such as image generation, editing, customization, and composition. GenArtist [86] provides a unified image generation and editing system, coordinated by a multimodal large language model (MLLM) agent. UniVG [87] treats multi-modal inputs as unified conditions with a single set of weights to enable various downstream applications. As research in this domain advances, it is expected that increasingly unified models will emerge, capable of addressing a broader spectrum of image generation and editing tasks.

Autoregressive models. Autoregressive (AR) models de

将序列的联合分布分解为条件概率的乘积,从而依次根据所有先前生成的元素来预测每个元素。该范式最初为语言建模而设计,已成功通过将图像映射为一维离散代币序列(像素、图像补丁或潜在代码)而被应用于视觉领域。形式上,给定序列 x = ( x 1 , x 2 , … , x N ) x = (x_{1}, x_{2}, \dots, x_{N}) x=(x1,x2,…,xN) ,模型被训练为在条件化于所有前序元素的情况下生成每个元素:

p ( x ) = ∏ i = 1 N p ( x i ∣ x 1 , x 2 , … , x i − 1 ; θ ) . (4) p (x) = \prod_ {i = 1} ^ {N} p \left(x _ {i} \mid x _ {1}, x _ {2}, \dots , x _ {i - 1}; \theta\right). \tag {4} p(x)=i=1∏Np(xi∣x1,x2,…,xi−1;θ).(4)

其中 θ \theta θ 是模型参数。训练目标是最小化负对数似然(NLL)损失:

L ( θ ) = − ∑ i = 1 N log p ( x i ∣ x 1 , x 2 , … , x i − 1 ; θ ) . (5) \mathcal {L} (\theta) = - \sum_ {i = 1} ^ {N} \log p \left(x _ {i} \mid x _ {1}, x _ {2}, \dots , x _ {i - 1}; \theta\right). \tag {5} L(θ)=−i=1∑Nlogp(xi∣x1,x2,…,xi−1;θ).(5)

如图4所示,现有方法基于序列表示策略分为三类:基于像素、基于代币和多代币模型。

- 基于像素的模型。PixelRNN [88] 是下一个像素预测的开创性方法。它将二维图像转换为一维像素序列,并使用 LSTM 层基于先前生成的值按序生成每个像素。虽然在建模空间依赖方面有效,但它存在计算成本高的问题。

PixelCNN[89] 引入了扩张卷积,以更高效地捕捉长程像素依赖,而 PixelCNN++ [90] 利用离散化对数混合似然和架构改进来提高图像质量和效率。一些先进工作 [91] 还提出了并行化方法,以降低计算开销并实现更快的生成,尤其适用于高分辨率图像。

2)基于代币的模型。受自然语言处理范式启发,基于代币的自回归模型将图像转换为紧凑的离散代币序列,大幅缩短序列长度并支持高分辨率的合成。该过程从向量量化(VQ)开始:

一个通过重建和约束损失训练的编码器-解码器学习出紧凑的潜在索引码本,然后仅解码器Transformer对这些代币的条件分布进行建模[92]。典型的VQ模型包括VQ-VAE-2[93], VQGAN[32], ViT-VQGAN[94], 等[95], [96], [97]。许多工作致力于增强仅解码器

Transformer 模型。LlamaGen [24] 将 VQGAN 分词器应用于 LLaMA 骨干网络 [1], [2], 在与 DiTs 可比的性能下表明随着参数量增加,生成质量有所提升。与此同时,像 DeLVM [98] 这样的数据高效变体在显著减少数据量的情况下达到相当的逼真度,而诸如 AiM [26],、ZigMa [99], 和 DiM [100] 的模型则集成了线性或门控注意力层

从Mamba[101]提供更快的推理和更出色的性能。为丰富上下文建模,提出了随机和混合解码策略。像SAIM[102], RandAR[103], 和RAR[104]这样的方法通过随机重排补丁预测来克服僵化的光栅偏差,

while SAR [105] 将因果学习推广到任意顺序和跳跃间隔。混合框架进一步融合范式:RAL [106]使用对抗策略梯度来

缓解暴露偏差,ImageBART[107]将分层扩散更新与自回归解码交错进行,DisCo-Diff[108]则通过离散潜变量增强扩散解码器以获得同类最佳的FID。

- 多个代币的方法。为提高生成效率,近期的自回归模型已从生成单个代币转向将多个代币作为一组进行预测,在不损失质量的情况下实现了显著提速。下一补丁预测(NPP)[109] 将图像令牌聚合为具有高信息密度的补丁级标记,从而显著减少序列长度。类似地,下一块预测(NBP)[110] 将分组扩展到较大的空间块,例如行或整个帧。相邻自回归(NAR) [111] 提出使用局部的“下一邻居”机制向外预测,而并行自回归(PAR) [112] 则将代币划分为不相交的子集以实现并发解码。MAR [25] 放弃了分-

放弃了固定的标记化和固定顺序,转而采用使用扩散损失训练的连续表示。除了空间分组之外,VAR [113] 引入了粗到细的下一级尺度范式,这启发了各种高级方法,

包括FlowAR[114]、M-VAR[115]、FastVAR[116]和FlexVAR[117]。一些基于频率的方法在频谱上将生成过程分解:FAR[118]和NFIG[119]合成

低频结构,然后再细化高频细节。

xAR [120] 抽象地统一了自回归单元,包括补丁、单元、尺度或整个图像,在单一框架下。这些多标记方法展示了为在现代图像生成中平衡保真度、效率和可扩展性而定义适当自回归单元的重要性,

图像生成。

控制机制也已被集成到自回归解码器中以实现更精确的编辑。ControlAR [121] 在解码过程中引入了诸如边缘图和深度线索等空间约束,从而允许对标记级编辑进行细粒度控制。ControlVAR [122] 通过在图像级特征上实现尺度感知条件化进一步推进了这一概念,增强了一致性和可编辑性。CAR [123] 在类似概念上进行了阐述,聚焦于自回归模型中的高级控制机制,以增强视觉输出的细节和适应性。对于涉及多个对象或时间上一致序列的复杂场景,

Many-to-Many Diffusion (M2M) [124] 将自回归框架适配用于多帧生成,

eration,确保图像之间的语义和时序一致性。MSGNet[125]将VQ-VAE与自回归建模相结合,以在场景中的多个实体之间保留空间-语义对齐。在医疗领域,MVG[126]将自回归图像到图像生成扩展到分割、合成和去噪等任务,通过以成对的提示-图像输入作为条件来实现这些任务。这些文本-

到图像生成的自回归方法提供了模型架构和视觉建模方法的基础,有效推进了用于理解和生成的统一多模态模型的研究。

3 统一多模态模型:用于理解和生成

统一多模态模型旨在构建一个能够同时理解和生成数据的单一架构

fine the joint distribution of a sequence by factorizing it into a product of conditional probabilities, whereby each element is predicted in turn based on all previously generated elements. This paradigm, originally devised for language modeling, has been successfully adapted to vision by mapping an image to a 1D sequence of discrete tokens (pixels, patches, or latent codes). Formally, given a sequence x = ( x 1 , x 2 , … , x N ) x = (x_{1},x_{2},\dots,x_{N}) x=(x1,x2,…,xN) , the model is trained to generate each element by conditioning all preceding elements:

p ( x ) = ∏ i = 1 N p ( x i ∣ x 1 , x 2 , … , x i − 1 ; θ ) . (4) p (x) = \prod_ {i = 1} ^ {N} p \left(x _ {i} \mid x _ {1}, x _ {2}, \dots , x _ {i - 1}; \theta\right). \tag {4} p(x)=i=1∏Np(xi∣x1,x2,…,xi−1;θ).(4)

where θ \theta θ is the model parameters. The training objective is to minimize the negative log-likelihood(NLL) loss:

L ( θ ) = − ∑ i = 1 N log p ( x i ∣ x 1 , x 2 , … , x i − 1 ; θ ) . (5) \mathcal {L} (\theta) = - \sum_ {i = 1} ^ {N} \log p \left(x _ {i} \mid x _ {1}, x _ {2}, \dots , x _ {i - 1}; \theta\right). \tag {5} L(θ)=−i=1∑Nlogp(xi∣x1,x2,…,xi−1;θ).(5)

As shown in Fig. 4, existing methods are divided into three types based on sequence representation strategies: pixel-based, token-based, and multiple-token-based models.

-

Pixel-based models. PixelRNN [88] was the pioneering method for next-pixel prediction. It transforms a 2D image into a 1D sequence of pixels and employs LSTM layers to sequentially generate each pixel based on previously generated values. While effective in modeling spatial dependencies, it suffers from high computational costs. PixelCNN [89] introduces dilated convolutions to more efficiently capture long-range pixel dependencies, while PixelCNN++ [90] leverages a discretized logistic mixture likelihood and architectural refinements to enhance image quality and efficiency. Some advanced works [91] have also proposed parallelization methods to reduce computational overhead and enable faster generation, particularly for high-resolution images.

-

Token-based models. Inspired by natural language processing paradigms, token-based AR models convert images into compact sequences of discrete tokens, greatly reducing sequence length and enabling high-resolution synthesis. This process begins with vector quantization (VQ): an encoder-decoder trained with reconstruction and commitment losses learns a compact codebook of latent indices, after which a decoder-only transformer models the conditional distribution over those tokens [92]. Typical VQ models include VQ-VAE-2 [93], VQGAN [32], ViT-VQGAN [94], and others [95], [96], [97] Many works have been investigated to enhance the decoder-only transformer models. LlamaGen [24] applies the VQGAN tokenizer to LLaMA backbones [1], [2], achieving comparable performance with DiTs and showing that generation quality improves with the increase of parameters. In parallel, data-efficient variants like DeLVM [98] achieve comparable fidelity with substantially less data, and models such as AiM [26], ZigMa [99], and DiM [100] integrate linear or gated attention layers from Mamba [101] to deliver faster inference and superior performance. To enrich contextual modeling, stochastic and hybrid decoding strategies have been proposed. Methods like SAIM [102], RandAR [103], and RAR [104] randomly permute patch predictions to overcome rigid raster biases, while SAR [105] generalizes causal learning to arbitrary orders and skip intervals. Hybrid frameworks further blend paradigms: RAL [106] uses adversarial policy gradients to

mitigate exposure bias, ImageBART [107] interleaves hierarchical diffusion updates with AR decoding, and DisCo-Diff [108] augments diffusion decoders with discrete latent for best-in-class FID.

- Multiple-tokens-based methods. To improve generation efficiency, recent AR models have shifted from generating individual tokens to predicting multiple tokens as a group, achieving significant speedups without quality loss. Next Patch Prediction (NPP) [109] aggregates image tokens into patch-level tokens with high information density, thus significantly reducing sequence length. Similarly, Next Block Prediction (NBP) [110] extends grouping to large spatial blocks, such as rows or entire frames. Neighboring AR (NAR) [111] proposes to predict outward using a localized “next-neighbor” mechanism, and Parallel Autoregression (PAR) [112] partitions tokens into disjoint subsets for concurrent decoding. MAR [25] abandons discrete tokenization and fixed ordering in favor of continuous representations trained with a diffusion loss. Beyond spatial grouping, VAR [113] introduced a coarse-to-fine next-scale paradigm, which inspired various advanced methods, including FlowAR [114], M-VAR [115], FastVAR [116], and FlexVAR [117]. Some frequency-based methods decompose generation spectrally: FAR [118] and NFIG [119] synthesize low-frequency structures before refining high-frequency details. xAR [120] abstractly unifies autoregressive units, including patches, cells, scales, or entire images, under a single framework. These multiple-token methods demonstrate the importance of defining appropriate autoregressive units for balancing fidelity, efficiency, and scalability in modern image generation.

Control mechanisms have also been integrated into autoregressive decoders for more precise editing. ControlAR [121] introduces spatial constraints such as edge maps and depth cues during decoding, allowing fine-grained control over token-level edits. ControlVAR [122] further advances this concept by implementing scale-aware conditioning on image-level features, enhancing coherence and editability. CAR [123] elaborates on a similar concept, focusing on advanced control mechanisms in autoregressive models to enhance the detail and adaptability of visual outputs. For complex scenarios involving multiple objects or temporally coherent sequences, Many-to-Many Diffusion (M2M) [124] adapts the autoregressive framework for multi-frame generation, ensuring semantic and temporal consistency across images. MSGNet [125] combines VQ-VAE with autoregressive modeling to preserve spatial-semantic alignment across multiple entities in a scene. In the medical domain, MVG [126] extends autoregressive image-to-image generation to tasks such as segmentation, synthesis, and denoising by conditioning on paired prompt-image inputs. These text-to-image generation AR methods provide the basics of the model architecture and visual modeling methods, effectively advancing research on unified multimodal models for understanding and generation.

3 UNIFIED MULTIMODAL MODELS FOR UNDERSTANDING AND GENERATION

Unified multimodal models aim to build a single architecture capable of both understanding and generating data

统一多模态理解与生成模型概览。该表根据骨干网络、编码器-解码器架构以及所使用的具体扩散或自回归模型对模型进行分类。表中包含有关模型、编码器、解码器以及图像生成中使用的掩码的信息,并提供了这些模型的发布日期,突出了多模态架构随时间的发展。

表1

| 模型 | Type | 架构 | Date | |||

| 骨干网络 | 理解编码器 | 生成编码器 | 生成解码器 | |||

| 扩散模型 | ||||||

| Dual Diffusion [127] | a | D-DiT | SD-VAE | SD-VAE | Bidirect. | |

| UniDisc [128] | a | DiT | MAGVIT-v2 | MAGVIT-v2 | Bidirect. | |

| MMaDA [129] | a | LLaDA | MAGVIT-v2 | MAGVIT-v2 | Bidirect. | |

| FUDOKI [130] | a | DeepSeek-LLM | SigLIP | VQGAN | VQGAN | Bidirect. |

| Muddit [131] | a | Meissonic (MM-DiT) | VQGAN | VQGAN | Bidirect. | |

| 自回归模型 | ||||||

| LWM [29] | b-1 | LLaMa-2 | VQGAN | VQGAN | 因果 | |

| Chameleon [30] | b-1 | LLaMa-2 | VQ-IMG | VQ-IMG | 因果 | |

| ANOLE [132] | b-1 | LLaMa-2 | VQ-IMG | VQ-IMG | 因果 | |

| Emu3 [133] | b-1 | LLaMa-2 | SBER-MoVQGAN | SBER-MoVQGAN | 因果 | |

| MMAR [134] | b-1 | Qwen2 | SD-VAE + EmbeddingViT | 扩散MLP | Bidirect. | |

| Orthus [135] | b-1 | Chameleon | VQ-IMG+视觉嵌入。 | 扩散MLP | 因果 | |

| SynerGen-VL [136] | b-1 | InterLM2 | SBER-MoVQGAN | SBER-MoVQGAN | 因果 | |

| Liquid [137] | b-1 | GEMMA | VQGAN | VQGAN | 因果 | |

| UGen [138] | b-1 | TinyLlama | SBER-MoVQGAN | SBER-MoVQGAN | 因果 | |

| Harmon [139] | b-1 | Qwen2.5 | MAR | MAR | Bidirect. | |

| TokLIP [140] | b-1 | Qwen2.5 | VQGAN+SigLIP | VQGAN | 因果 | |

| Selftok [141] | b-1 | LLaMA3.1 | SD3-VAE+MMDiT | SD3 | 因果 | |

| Emu [142] | b-2 | LLaMA | EVA-CLIP | SD | 因果 | |

| LaVIT [143] | b-2 | LLaMA | EVA-CLIP | SD-1.5 | 因果 | |

| DreamLLM [34] | b-2 | LLaMA | OpenAI-CLIP | SD-2.1 | 因果 | |

| Emu2 [33] | b-2 | LLaMA | EVA-CLIP | SDXL | 因果 | |

| VL-GPT [35] | b-2 | LLaMA | OpenAI-CLIP | IP-Adapter | 因果 | |

| MM-Interleaved [144] | b-2 | Vicuna | OpenAI-CLIP | SD-v2.1 | 因果 | |

| Mini-Gemini [145] | b-2 | Gemma&Vicuna | OpenAI-CLIP+ConvNext | SDXL | 因果 | |

| VILA-U [146] | b-2 | LLaMA-2 | Siglip+RQ | RQ-VAE | 因果 | |

| PUMA [147] | b-2 | LLaMA-3 | OpenAI-CLIP | SDXL | Bidirect. | |

| MetaMorph [148] | b-2 | LLaMA | Siglip | SD-1.5 | 因果 | |

| ILLUME [149] | b-2 | Vicuna | UNIT | SDXL | 因果 | |

| UniTok [150] | b-2 | LLaMA-2 | ViTamin | ViTamin | 因果 | |

| QLIP [151] | b-2 | LLaMA-3 | QLIP-ViT+BSQ | BSQ-AE | 因果 | |

| DualToken [152] | b-2 | Qwen2.5 | Siglip | RQVAE | 因果 | |

| UniFork [153] | b-2 | Qwen2.5 | Siglip+RQ | RQ-VAE | 因果 | |

| UniCode2 [154] | b-2 | Qwen2.5 | Siglip+RQ | FLUX.1-dev/SD-1.5 | 因果 | |

| UniWorld [155] | b-2 | Qwen2.5-VL | Siglip2 | DiT | Bidirect. | |

| Pisces [156] | b-2 | LLaMA-3.1 | Siglip | EVA-CLIP | 扩散 | 因果 |

| Tar [157] | b-2 | Qwen2.5 | Siglip2+VQ | VQGAN/SANA | 因果 | |

| OmniGen2 [158] | b-2 | Qwen2.5-VL | Siglip | OmniGen | 因果 | |

| Ovis-U1 [159] | b-2 | Ovis | AimV2 | MMDiT | 因果 | |

| X-Omni [160] | b-2 | Qwen2.5-VL | QwenViT | Siglip | FLUX | 因果 |

| Qwen-Image [161] | b-2 | Qwen2.5-VL | QwenViT | MMDiT | 因果 | |

| Bifrost-1 [162] | b-2 | Qwen2.5-VL | QwenViT | ViT | FLUX | 因果 |

| SEED [163] | b-3 | OPT | SEED 分词器 | 可学习查询 | SD | 因果 |

| SEED-LLaMA [164] | b-3 | LLaMa-2 & Vicuna | SEED 分词器 | 可学习查询 | unCLIP-SD | 因果 |

| SEED-X [165] | b-3 | LLaMa-2 | SEED 分词器 | 可学习查询 | SDXL | 因果 |

| MetaQueriesies [166] | b-3 | LLaVA&Qwen2.5-VL | Siglip | 可学习查询 | Sana | 因果 |

| Nexus-Gen [167] | b-3 | Qwen2.5-VL | QwenViT | 可学习查询 | FLUX | 因果 |

| Ming-Lite-Uni [168] | b-3 | M2-omni | NavIT | 可学习查询 | Sana | 因果 |

| BLIP3-o [169] | b-3 | Qwen2.5-VL | OpenAI-CLIP | 可学习查询 | Lumina-Next | 因果 |

| OpenUni [170] | b-3 | InternVL3 | OpenAI-CLIP | 可学习查询 | Sana | 因果 |

| Ming-Omni [171] | b-3 | Ling | OpenAI-ViT | 可学习查询 | 多尺度 DiT | 因果 |

| UniLIP [172] | b-3 | InternVL3 | OpenAI-ViT | 可学习查询 | Sana | 因果 |

| TBAC-UniImage [173] | b-3 | Qwen2.5-VL | QwenViT | 可学习查询 | Sana | 因果 |

| Janus [174] | b-4 | DeepSeek-LLM | Siglip | VQGAN | VQGAN | Casual |

| Janus-Pro [175] | b-4 | DeepSeek-LLM | Siglip | VQGAN | VQGAN | Casual |

| OmniMamba [176] | b-4 | Mamba-2 | DINO-v2+Siglip | VQGAN | VQGAN | 因果 |

| UniFluid [177] | b-4 | Gemma-2 | Siglip | SD-VAE | 扩散MLP | 因果 |

| MindOmni [178] | b-4 | Qwen2.5-VL | QwenViT | VAE | OmniGen | 因果 |

| Skywork UniPic [179] | b-4 | Qwen2.5 | SigLIP2 | SDXL-VAE | SDXL-VAE | 因果 |

| MUSE-VL [180] | b-5 | Qwen-2.5&Yi-1.5 | SigLIP | VQGAN | VQGAN | 因果 |

| Tokenflow [181] | b-5 | Vicuna&Qwen-2.5 | OpenAI-CLIP | MSVQ | MSVQ | 因果 |

| VARGPT [182] | b-5 | Vicuna-1.5 | OpenAI-CLIP | MSVQ | VAR-D30 | 因果 |

| SemHiTok [183] | b-5 | Qwen2.5 | Siglip | ViT | ViT | 因果 |

| VARGPT-1.1 [184] | b-5 | Qwen2 | SigLIP | MSVQ | Infinity | 因果 |

| ILLUME+ [185] | b-5 | Qwen2.5 | QwenViT | MoVQGAN | SDXL | 因果 |

| UniToken [186] | b-5 | Chameleon | SigLIP | VQ-IMG | VQGAN | 因果 |

| Show-o2 [187] | b-5 | Qwen2.5 | Wan-3DVAE + Siglip | Wan-3DVAE | Wan-3DVAE | 因果 |

融合自回归与扩散模型

| Transfusion [38] | c-1 | LLaMA-2 | SD-VAE | SD-VAE | Bidirect. | 2024-08 |

| Show-o [39] | c-1 | LLaVA-v1.5-Phi | MAGVIT-v2 | MAGVIT-v2 | Bidirect. | 2024-08 |

| MonoFormer [37] | c-1 | TinyLlama | SD-VAE | SD-VAE | Bidirect. | 2024-09 |

| LMFusion [188] | c-1 | LLaMA | SD-VAE+UNet下采样。 | SD-VAE+UNet上采样。 | Bidirect. | 2024-12 |

| Janus-flow [189] | c-2 | DeepSeek-LLM | Siglip | SDXL-VAE | 因果 | 2024-11 |

| 莫高 [190] | c-2 | Qwen2.5 | Siglip+SDXL-VAE | SDXL-VAE | Bidirect. | 2025-05 |

| BAGEL [191] | c-2 | Qwen2.5 | SigLIP | FLUX-VAE | FLUX-VAE | 2025-05 |

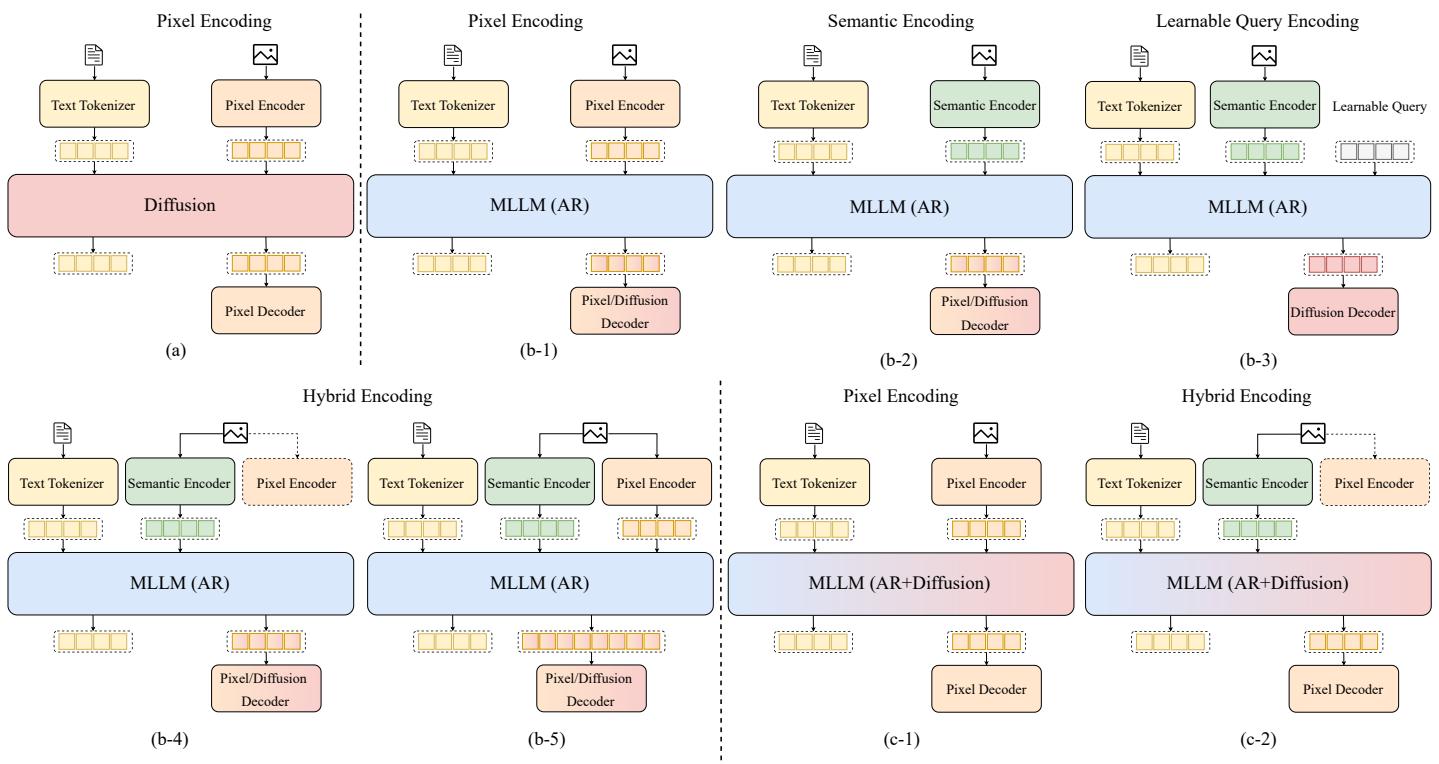

Overview of Unified Multimodal Understanding and Generation Models. This table categorizes models based on their backbone, encoder-decoder architecture, and the specific diffusion or autoregressive models used. It includes information on model, encoder, decoder and the mask used in image generation. The release dates of these models are also provided, highlighting the evolution of multimodal architectures over time.

TABLE 1

| Model | Type | Architecture | Date | ||||

| Backbone | Und. Enc. | Gen. Enc. | Gen. Dec. | Mask | |||

| Diffusion Model | |||||||

| Dual Diffusion [127] | a | D-DiT | SD-VAE | SD-VAE | Bidirect. | 2024-12 | |

| UniDisc [128] | a | DiT | MAGVIT-v2 | MAGVIT-v2 | Bidirect. | 2025-03 | |

| MMDA [129] | a | LLaDA | MAGVIT-v2 | MAGVIT-v2 | Bidirect. | 2025-05 | |

| FUDOKI [130] | a | DeepSeek-LLM | SigLIP | VQGAN | VQGAN | Bidirect. | 2025-05 |

| Muddit [131] | a | Meissonic (MM-DiT) | VQGAN | VQGAN | Bidirect. | 2025-05 | |

| Autoregressive Model | |||||||

| LWM [29] | b-1 | LLaMa-2 | VQGAN | VQGAN | Causal | 2024-02 | |

| Chameleon [30] | b-1 | LLaMa-2 | VQ-IMG | VQ-IMG | Causal | 2024-05 | |

| ANOLE [132] | b-1 | LLaMa-2 | VQ-IMG | VQ-IMG | Causal | 2024-07 | |

| Emu3 [133] | b-1 | LLaMA-2 | SBER-MoVQGAN | SBER-MoVQGAN | Causal | 2024-09 | |

| MMAR [134] | b-1 | Qwen2 | SD-VAE + EmbeddingViT | Diffusion MLP | Bidirect. | 2024-10 | |

| Orthus [135] | b-1 | Chameleon | VQ-IMG+Vision embed. | Diffusion MLP | Causal | 2024-11 | |

| SynerGen-VL [136] | b-1 | InterLM2 | SBER-MoVQGAN | SBER-MoVQGAN | Causal | 2024-12 | |

| Liquid [137] | b-1 | GEMMA | VQGAN | VQGAN | Causal | 2024-12 | |

| UGen [138] | b-1 | TinyLlama | SBER-MoVQGAN | SBER-MoVQGAN | Causal | 2025-03 | |

| Harmon [139] | b-1 | Qwen2.5 | MAR | MAR | Bidirect. | 2025-03 | |

| TokLIP [140] | b-1 | Qwen2.5 | VQGAN+SigLIP | VQGAN | Causal | 2025-05 | |

| Selftok [141] | b-1 | LLaMA3.1 | SD3-VAE+MMDiT | SD3 | Causal | 2025-05 | |

| Emu [142] | b-2 | LLaMA | EVA-CLIP | SD | Causal | 2023-07 | |

| LaVIT [143] | b-2 | LLaMA | EVA-CLIP | SD-1.5 | Causal | 2023-09 | |

| DreamLLM [34] | b-2 | LLaMA | OpenAI-CLIP | SD-2.1 | Causal | 2023-09 | |

| Emu2 [33] | b-2 | LLaMA | EVA-CLIP | SDXL | Causal | 2023-12 | |

| VL-GPT [35] | b-2 | LLaMA | OpenAI-CLIP | IP-Adapter | Causal | 2023-12 | |

| MM-Interleaved [144] | b-2 | Vicuna | OpenAI-CLIP | SD-v2.1 | Causal | 2024-01 | |

| Mini-Gemini [145] | b-2 | Gemma&Vicuna | OpenAI-CLIP+ConvNext | SDXL | Causal | 2024-03 | |

| VILA-U [146] | b-2 | LLaMA-2 | SigLIP+RQ | RQ-VAE | Causal | 2024-09 | |

| PUMA [147] | b-2 | LLaMA-3 | OpenAI-CLIP | SDXL | Bidirect. | 2024-10 | |

| MetaMorph [148] | b-2 | LLaMA | SigLIP | SD-1.5 | Causal | 2024-12 | |

| ILLUME [149] | b-2 | Vicuna | UNIT | SDXL | Causal | 2024-12 | |

| UniTok [150] | b-2 | LLaMA-2 | ViTamin | ViTamin | Causal | 2025-02 | |

| QLIP [151] | b-2 | LLaMA-3 | QLIP-ViT+BSQ | BSQ-AE | Causal | 2025-02 | |

| DualToken [152] | b-2 | Qwen2.5 | SigLIP | RQVAE | Causal | 2025-03 | |

| UniFork [153] | b-2 | Qwen2.5 | SigLIP+RQ | RQ-VAE | Causal | 2025-06 | |

| UniCode2 [154] | b-2 | Qwen2.5 | SigLIP+RQ | FLUX.1-dev / SD-1.5 | Causal | 2025-06 | |

| UniWorld [155] | b-2 | Qwen2.5-VL | SigLIP2 | DIt | Bidirect. | 2025-06 | |

| Pisces [156] | b-2 | LLaMA-3.1 | SigLIP | EVA-CLIP | Diffusion | Causal | 2025-06 |

| Tar [157] | b-2 | Qwen2.5 | SigLIP2+VQ | VQGAN / SANA | Causal | 2025-06 | |

| OmniGen2 [158] | b-2 | Qwen2.5-VL | SigLIP | OmniGen | Causal | 2025-06 | |

| Ovis-U1 [159] | b-2 | Ovis | AimV2 | MMDIT | Causal | 2025-06 | |

| X-Omni [160] | b-2 | Qwen2.5-VL | QwenViT | Siglip | FLUX | Causal | 2025-07 |

| Qwen-Image [161] | b-2 | Qwen2.5-VL | QwenViT | MMDIT | Causal | 2025-08 | |

| Bifrost-1 [162] | b-2 | Qwen2.5-VL | QwenViT | ViT | FLUX | Causal | 2025-08 |

| SEED [163] | b-3 | OPT | SEED Tokenizer | Learnable Query | SD | Causal | 2023-07 |

| SEED-LLaMA [164] | b-3 | LLaMa-2 & Vicuna | SEED Tokenizer | Learnable Query | unCLIP-SD | Causal | 2023-10 |

| SEED-X [165] | b-3 | LLaMa-2 | SEED Tokenizer | Learnable Query | SDXL | Causal | 2024-04 |

| MetaQueries [166] | b-3 | LLaVA&Qwen2.5-VL | SigLIP | Learnable Query | Sana | Causal | 2025-04 |

| Nexus-Gen [167] | b-3 | Qwen2.5-VL | QwenViT | Learnable Query | FLUX | Causal | 2025-04 |

| Ming-Lite-Uni [168] | b-3 | M2-omni | NaViT | Learnable Query | Sana | Causal | 2025-05 |

| BLIP3-o [169] | b-3 | Qwen2.5-VL | OpenAI-CLIP | Learnable Query | Lumina-Next | Causal | 2025-05 |

| OpenUni [170] | b-3 | InternVL3 | InternViT | Learnable Query | Sana | Causal | 2025-05 |

| Ming-Omni [171] | b-3 | Ling | QwenViT | Learnable Query | Multi-scale DiT | Causal | 2025-06 |

| UniLIP [172] | b-3 | InternVL3 | InternViT | Learnable Query | Sana | Causal | 2025-07 |

| TBAC-Unilmage [173] | b-3 | Qwen2.5-VL | QwenViT | Learnable Query | Sana | Causal | 2025-08 |

| Janus [174] | b-4 | DeepSeek-LLM | SigLIP | VQGAN | VQGAN | Causal | 2024-10 |

| Janus-Pro [175] | b-4 | DeepSeek-LLM | SigLIP | VQGAN | VQGAN | Causal | 2025-01 |

| OmniMamba [176] | b-4 | Mamba-2 | DINO-v2+SigLIP | VQGAN | VQGAN | Causal | 2025-03 |

| Unifluid [177] | b-4 | Gemma-2 | SigLIP | SD-VAE | Diffusion MLP | Causal | 2025-03 |

| MindOmni [178] | b-4 | Qwen2.5-VL | QwenViT | VAE | OmniGen | Causal | 2025-06 |

| Skywork UniPic [179] | b-4 | Qwen2.5 | SigLIP2 | SDXL-VAE | SDXL-VAE | Causal | 2025-08 |

| MUSE-VL [180] | b-5 | Qwen-2.5&Yi-1.5 | SigLIP | VQGAN | VQGAN | Causal | 2024-11 |

| Tokenflow [181] | b-5 | Vicuna&Qwen-2.5 | OpenAI-CLIP | MSVQ | MSVQ | Causal | 2024-12 |

| VARGPT [182] | b-5 | Vicuna-1.5 | OpenAI-CLIP | MSVQ | VAR-d30 | Causal | 2025-01 |

| SemHiTok [183] | b-5 | Qwen2.5 | SigLIP | ViT | ViT | Causal | 2025-03 |

| VARGPT-1.1 [184] | b-5 | Qwen2.5 | SigLIP | MSVQ | Infinity | Causal | 2025-04 |

| ILLUME+ [185] | b-5 | Qwen2.5 | QwenViT | MoVQGAN | SDXL | Causal | 2025-04 |

| UniToken [186] | b-5 | Chameleon | SigLIP | VQ-IMG | VQGAN | Causal | 2025-04 |

| Show-o2 [187] | b-5 | Qwen2.5 | Wan-3DVAE + SigLIP | Wan-3DVAE | Wan-3DVAE | Causal | 2025-06 |

| Fused Autoregressive and Diffusion Model | |||||||

| Transfusion [38] | c-1 | LLaMA-2 | SD-VAE | SD-VAE | Bidirect. | 2024-08 | |

| Show-o [39] | c-1 | LLaVA-v1.5-Phi | MAGVIT-v2 | MAGVIT-v2 | Bidirect. | 2024-08 | |

| MonoFormer [37] | c-1 | TinyLLaMA | SD-VAE | SD-VAE+UNet down. | Bidirect. | 2024-09 | |

| LFusion [188] | c-1 | LLaMA | SD-VAE+UNet down. | 2024-12 | |||

| Janus-flow [189] | c-2 | DeepSeek-LLM | SigLIP | SDXL-VAE | SDXL-VAE | Causal | 2024-11 |

| Mogao [190] | c-2 | Qwen2.5 | SigLIP+SDXL-VAE | SDXL-VAE | Bidirect. | 2025-05 | |

| BAGEL [191] | c-2 | Qwen2.5 | SigLIP | FLUX-VAE | Bidirect. | 2025-05 | |

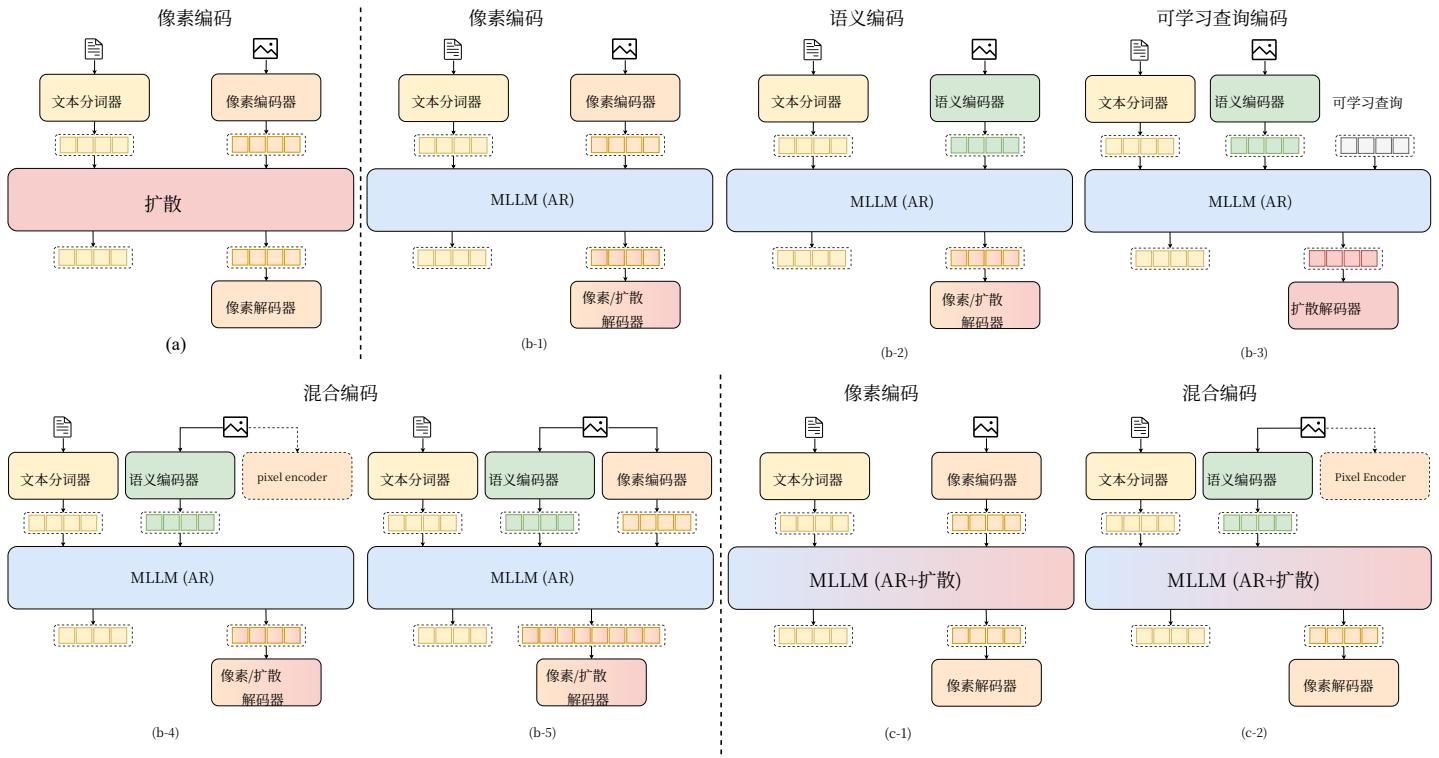

图5.统一多模态理解与生成模型的分类。根据骨干架构,这些模型分为三大类:扩散、MLLM(AR)和MLLM(AR + Diffusion)。每一类又根据所采用的编码策略细分,包括像素编码、语义编码、可学习查询编码和混合编码。我们展示了这些类别内的架构变体及其对应的编码器-解码器配置。

表2

支持除图像和文本之外的模态输入/输出的任意到任意多模态模型概览。本表对支持

varie模砸码器和砸,用d阅凿出的韵意动韵类,以模布的这些模型远近年来向更广运多模交匝的转变arc hitecture mo mat

| 模型 | 架构 | Date | |||

| 骨干网络 | 模态编码器 | 模态解码器 | Mask | ||

| Next-GPT [192] | Vicuna | ImageBind | AudioLDM+SD-1.5+Zeroscope-v2 | 因果 | 2023-09 |

| Unified-IO 2 [193] | T5 | 音频频谱变换器+视觉 ViT | 音频 ViT-VQGAN + 视觉 VQGAN | 因果 | 2023-12 |

| Video-LaVIT [194] | LLaVA-1.5 | LaVIT+运动 VQ-VAE | SVD img2vid-xt | 因果 | 2024-02 |

| AnyGPT [195] | LLaMa-2 | EnCodec+SEED 分词器+SpeechTokenizer | EnCodec+SD+SoundStorm | 因果 | 2024-02 |

| X-VILA [196] | Vicuna | ImageBind | AudioLDM+SD-1.5+Zeroscope-v2 | 因果 | 2024-05 |

| MIO [197] | Yi-Base | SpeechTokenizer+SEED-Tokenizer | SpeechTokenizer+SEED 分词器 | 因果 | 2024-09 |

| Spider [198] | LLaMA-2 | ImageBind | AudioLDM+SD-1.5+Zeroscope-v2 | 因果 | 2024-11 |

| OmniFlow [199] | MMDiT | HiFiGen+SD-VAE+Flan-T5 | +Grounding DINO+SAM | Bidirect. | 2024-12 |

| M2-omni [200] | LLaMA-3 | paraformer-zh+NaViT | HiFiGen+SD-VAE+TinyLlama | Casual | 2025-02 |

跨越多种模态。这些模型旨在以统一的方式处理不同形式的输入(例如文本、图像、视频、音频)并在一种或多种模态中生成输出。一个典型的统一多模态框架可以抽象为三个核心组件:将不同输入模态投射到表示空间的模态特定编码器;整合多模态信息并实现跨模态推理的模态融合骨干;以及在目标模态中生成输出(例如文本生成或图像合成)的模态特定解码器。

在本节中,我们主要关注支持视觉-语言理解与生成的统一多模态模型,即以图像和文本作为输入并生成文本或图像作为输出的模型。如图5所示,现有的统一模型大体可以

划分为三种主要类型:扩散模型、自回归模型,以及融合的自回归 + 扩散模型。对于自回归模型,我们进一步根据其模态编码方法将其分为四个子类别:基于像素的编码、基于语义的编码、可学习查询编码和混合编码。这些编码策略分别代表了处理视觉和文本数据的不同方式,从而在多模态表示的集成度和灵活性上产生差异。融合的自回归 + 扩散模型根据模态编码分为两类:基于像素的编码和混合编码。这些模型结合了自回归和扩散技术的特性,为更统一且高效的多模态生成提供了有前景的方法。

Fig. 5. Classification of Unified Multimodal Understanding and Generation Models. The models are divided into three main categories based on their backbone architecture: Diffusion, MLLM (AR), and MLLM (AR + Diffusion). Each category is further subdivided according to the encoding strategy employed, including Pixel Encoding, Semantic Encoding, Learnable Query Encoding, and Hybrid Encoding. We illustrate the architectural variations within these categories and their corresponding encoder-decoder configurations.

TABLE 2

Overview of Any-to-Any Multimodal Models Supporting Modal Input/Output Beyond Image and Text. This table categorizes models that support a variety of input and output modalities, including audio, music, image, video, and text. It includes information on the model’s backbone architecture, modality encoders and decoders, the type of attention mask used in vision generation, and the model release dates. These models exemplify the shift toward broader multimodal interactions in recent years.

| Model | Architecture | Date | |||

| Backbone | Modality Enc. | Modality Dec. | Mask | ||

| Next-GPT [192] | Vicuna | ImageBind | AudioLDM+SD-1.5+Zeroscope-v2 | Causal | 2023-09 |

| Unified-IO 2 [193] | T5 | Audio Spectrogram Transformer+Vision ViT | Audio ViT-VQGAN + Vision VQGAN | Causal | 2023-12 |

| Video-LaVIT [194] | LLaVA-1.5 | LaViT+Motion VQ-VAE | SVD img2vid-xt | Causal | 2024-02 |

| AnyGPT [195] | LLaMA-2 | Encodec+SEED Tokenizer+SpeechTokenizer | Encodec+SD+SoundStorm | Causal | 2024-02 |

| X-VILA [196] | Vicuna | ImageBind | AudioLDM+SD-1.5+Zeroscope-v2 | Causal | 2024-05 |

| MIO [197] | Yi-Base | SpeechTokenizer+SEED-Tokenizer | SpeechTokenizer+SEED Tokenizer | Causal | 2024-09 |

| Spider [198] | LLaMA-2 | ImageBind | AudioLDM+SD-1.5+Zeroscope-v2 +Grounding DINO+SAM | Causal | 2024-11 |

| OmniFlow [199] | MMDiT | HiFiGen+SD-VAE+Flan-T5 | HiFiGen+SD-VAE+TinyLlama | Bidirect. | 2024-12 |

| M2-omni [200] | LLaMA-3 | paraformer-zh+NaViT | CosyVoice-vocoder+SD-3 | Casual | 2025-02 |

across multiple modalities. These models are designed to process diverse forms of input (e.g., text, image, video, audio) and produce outputs in one or more modalities in a unified manner. A typical unified multimodal framework can be abstracted into three core components: modality-specific encoders that project different input modalities into a representation space; a modality-fusion backbone that integrates information from multiple modalities and enables cross-modal reasoning; and modality-specific decoders that generate output in the desired modality (e.g., text generation or image synthesis).

In this section, we primarily focus on unified multimodal models that support vision-language understanding and generation, i.e., models that take both image and text as input and produce either text or image as output. As shown in Fig. 5, existing unified models can be broadly

categorized into three main types: diffusion models, autoregressive models, and fused AR + diffusion models. For autoregressive models, we further classify them based on their modality encoding methods into four subcategories: pixel-based encoding, semantic-based encoding, learnable query-based encoding, and hybrid encoding. Each of these encoding strategies represents different ways of handling visual and textual data, leading to varying levels of integration and flexibility in the multimodal representations. Fused AR + diffusion models are divided into two subcategories based on modality encoding: pixel-based encoding and hybrid encoding. These models combine aspects of both autoregressive and diffusion techniques, offering a promising approach to more unified and efficient multimodal generation.

In the following sections, we will delve deeper into

每一类:第3.1节探讨基于扩散的模型,讨论它们在从噪声表示生成高质量图像和文本方面的独特优势。第3.2节聚焦于基于自回归的模型,详细说明不同编码方法如何影响它们在视觉-语言任务中的性能。第3.3节涵盖融合的AR + diffusion模型,审视这两种范式的结合如何增强多模态生成能力。最后,我们将讨论任意到任意的多模态模型,这类模型将该框架推广到超越视觉和语言的更广泛模态,如音频、视频和语音,旨在构建通用的、多用途的生成模型。

3.1扩散模型

扩散模型在图像生成领域取得了显著成功,这得益于若干关键优势。首先,与生成对抗网络(GANs)相比,它们提供了更高的样本质量,具有更好的模式覆盖能力,并缓解了诸如模式崩溃和训练不稳定性等常见问题 [201]。其次,训练目标——从略微扰动的数据中预测所添加的噪声——是一个简单的监督学习任务,避免了对抗性动态。第三,扩散模型高度灵活,允许在采样过程中融入各种条件信号,例如分类器引导[201]和无分类器引导[202],这提升了可控性和生成保真度。此外,噪声调度[203]和加速采样技术[204],[205]的改进显著降低了计算负担,使扩散模型越来越高效且具备可扩展性。

利用这些优势,研究人员已将扩散模型从单模态任务扩展到多模态生成,旨在在统一框架内支持文本与图像等输出。如图5(a)所示,在多模态扩散模型中,去噪过程不仅以时间步和噪声为条件,还以多模态上下文为条件,例如文本描述、图像或联合嵌入表示。这一扩展使不同模态之间能够同步生成,并允许在生成输出之间实现丰富的语义对齐。

一个具有代表性的例子是 Dual Diffusion [127], 它为联合文本和图像生成引入了双分支扩散过程。具体来说, 给定一对文本-图像, Dual Diffusion 首先使用预训练的 T5 encoder [23] 通过 softmax 概率建模对文本进行编码以获得离散文本表征, 然后使用来自 Stable Diffusion 的 VAE encoder [14] 对图像进行编码以获得连续的图像潜变量。文本和图像潜变量分别通过各自的前向扩散过程被加入噪声, 从而在每个时间步得到带噪的潜变量。在反向过程期间, 模型使用两个模态特定的去噪器联合去噪文本和图像潜变量: 一个基于 Transformer 的文本去噪器和一个基于 UNet 的图像去噪器。关键是, 在每个时间步, 去噪器引入跨模态条件化, 即文本潜变量对图像潜变量进行注意, 反之亦然, 使得在整个去噪轨迹中实现模态之间的语义对齐。去噪之后, 文本潜变量被解码为

通过T5解码器的自然语言,而图像潜变量通过VAE解码器被解码为高保真图像。训练由两项不同的损失项监督:图像分支最小化标准的噪声预测损失,而文本分支最小化对比对数损失。通过耦合这两条扩散链并引入显式的跨模态交互,Dual Diffusion能够从纯噪声生成连贯且可控的多模态内容。

不同于将离散文本扩散与基于 Stable Diffusion 的连续图像扩散相结合的 Dual Diffusion [127], [14], UniDisc [128] 采用了一个完全离散的扩散框架, 从头训练一个 Diffusion Transformer [206] 。它使用 LLaMA2 分词器 [2]对文本进行分词, 并通过 MAGVIT-v2 编码器 [207], 将图像转换为离散令牌, 从而实现两种模态在离散令牌空间中的统一。这些令牌经历离散的正向扩散过程, 在此过程中跨模态同时加入结构化噪声。在反向过程中, UniDisc 逐步对令牌进行去噪以生成连贯的序列。随后, LLaMA2 和 MAGVIT-v2 解码器将这些序列转换为高质量的文本和图像。通过采用完全离散的方法, UniDisc 能够同时细化文本和图像令牌, 提高推理效率并支持多样的跨模态条件控制。

与早期基于离散扩散的方法相比,FUDOKI [130] 引入了一种基于离散流匹配 [208] 的新型生成方法。在该框架下,FUDOKI 通过采用动力学最优、度量诱导的概率轨迹来建模噪声与数据分布之间的直接路径。该设计实现了一个连续的自我纠正机制,相较于早期模型中使用的简单掩码策略具有明显优势。FUDOKI 的模型架构基于 Janus-1.5B [174],但为支持统一的视觉-语言离散流建模做出了重要修改。其中一项关键改动是将标准的因果掩码替换为全注意力掩码,使每个令牌都能关注所有其他令牌,从而增强全局上下文理解。尽管该修改移除了显式的因果结构,模型仍通过将输出 logits 向后平移一位来支持下一个代币预测。另一个重要区别在于 FUDOKI 处理时间或损坏等级的方式。与扩散模型中所需的显式时间步嵌入不同,FUDOKI 直接从输入数据推断损坏状态。沿用 Janus-1.5B 的设计,FUDOKI 将理解与生成的处理路径解耦。为了图像理解,采用了 SigLIP 编码器[209] 来捕捉高层语义特征;而用于图像生成的则是来自 LlamaGen 的基于 VQGAN 的分词器 [24],它将图像编码为低层离散令牌序列。在输出阶段,Janus-1.5B 骨干网络生成的特征嵌入会传入模态特定的输出头,以生成最终的文本和图像输出。

类似地,Muddit [131] 引入了一个用于双向生成的统一模型,使用纯离散扩散框架来处理文本和图像。其架构特点是采用单一的 Multimodal DiffusionTransformer (MM-DiT),其架构设计与 FLUX [210] 相似。为了利用强大的图像先验,MM-DiT

each category: Section 3.1 explores diffusion-based models, discussing their unique advantages in terms of generating high-quality images and text from noisy representations. Section 3.2 focuses on autoregressive-based models, detailing how different encoding methods impact their performance in vision-language tasks. Section 3.3 covers fused AR + diffusion models, examining how the combination of these two paradigms can enhance multimodal generation capabilities. Finally, we extend our discussion to any-to-any multimodal models, which generalize this framework beyond vision and language to support a broader range of modalities such as audio, video, and speech, with the aim of building universal, general-purpose generative models.

3.1 Diffusion Models

Diffusion models have achieved remarkable success in the field of image generation owing to several key advantages. First, they provide superior sample quality compared to generative adversarial networks (GANs), offering better mode coverage and mitigating common issues such as mode collapse and training instability [201]. Second, the training objective—predicting the added noise from slightly perturbed data—is a simple supervised learning task that avoids adversarial dynamics. Third, diffusion models are highly flexible, allowing the incorporation of various conditioning signals during sampling, such as classifier guidance [201] and classifier-free guidance [202], which enhances controllability and generation fidelity. Furthermore, improvements in noise schedules [203] and accelerated sampling techniques [204], [205] have significantly reduced the computational burden, making diffusion models increasingly efficient and scalable.

Leveraging these strengths, researchers have extended diffusion models beyond unimodal tasks toward multimodal generation, aiming to support both text and image outputs within a unified framework. As shown in Fig. 5 (a), in multimodal diffusion models, the denoising process is conditioned not only on timestep and noise but also on multimodal contexts, such as textual descriptions, images, or joint embeddings. This extension enables synchronized generation across different modalities and allows for rich semantic alignment between generated outputs.

A representative example is Dual Diffusion [127], which introduces a dual-branch diffusion process for joint text and image generation. Specifically, given a text-image pair, Dual Diffusion first encodes the text using a pretrained T5 encoder [23] with softmax probability modeling to obtain discrete text representations, and encodes the image using the VAE encoder from Stable Diffusion [14] to obtain continuous image latents. Both text and image latents are independently noised through separate forward diffusion processes, resulting in noisy latent variables at each timestep. During the reverse process, the model jointly denoises the text and image latents using two modality-specific denoisers: a Transformer-based text denoiser and a UNet-based image denoiser. Crucially, at each timestep, the denoisers incorporate cross-modal conditioning, where the text latent attends to the image latent and vice versa, enabling semantic alignment between the modalities throughout the denoising trajectory. After denoising, the text latent is decoded into

natural language via a T5 decoder, and the image latent is decoded into a high-fidelity image via the VAE decoder. Training is supervised by two distinct loss terms: the image branch minimizes a standard noise prediction loss, while the text branch minimizes a contrastive log-loss. By coupling the two diffusion chains and introducing explicit cross-modal interactions, Dual Diffusion enables coherent and controllable multimodal generation from pure noise.

Unlike Dual Diffusion [127], which combines discrete text diffusion with continuous image diffusion via Stable Diffusion [14], UniDisc [128] employs a fully discrete diffusion framework to train a Diffusion Transformer [206] from scratch. It tokenizes text using the LLaMA2 tokenizer [2] and converts images into discrete tokens with the MAGVIT-v2 encoder [207], allowing unification of both modalities in a discrete token space. These tokens undergo a discrete forward diffusion process, where structured noise is added simultaneously across modalities. In the reverse process, UniDisc progressively denoises the tokens to generate coherent sequences. The LLaMA2 and MAGVIT-v2 decoders then transform these sequences into high-quality text and images. By adopting a fully discrete approach, UniDisc enables simultaneous refinement of text and image tokens, enhancing inference efficiency and supporting versatile cross-modal conditioning.

In contrast to earlier discrete diffusion-based methods, FUDOKI [130] introduces a novel generative approach based on a discrete flow matching [208]. Under this framework, FUDOKI models a direct path between noise and data distributions by employing a kinetic-optimal, metric-induced probability trajectory. This design enables a continuous self-correction mechanism, which provides a clear advantage over the simple masking strategies used in earlier models. FUDOKI’s model architecture is based on Janus-1.5B [174]. However, it introduces essential modifications to support unified vision-language discrete flow modeling. One key change is the replacement of the standard causal mask with a full attention mask. This allows every token to attend to all others, thereby enhancing global contextual understanding. Although this modification removes the explicit causal structure, the model still supports next-token prediction by shifting its output logits by one position. Another important distinction is in the way FUDOKI handles time or corruption levels. Instead of relying on explicit timestep embeddings, as required in diffusion models, FUDOKI infers the corruption state directly from the input data. Following Janus-1.5B, FUDOKI decouples the processing paths for understanding and generation. A SigLIP encoder [209] is employed to capture high-level semantic features for image understanding, while a VQGAN-based tokenizer from LlamaGen [24] encodes the image into a sequence of low-level discrete tokens for image generation. At the output stage, the feature embeddings generated by the Janus-1.5B backbone are passed through modality-specific output heads to produce the final text and image outputs.

In a similar vein, Muddit [131] introduces a unified model for bidirectional generation using a purely discrete diffusion framework to handle text and images. Its architecture features a single Multimodal Diffusion Transformer (MM-DiT) with an architectural design similar to that of FLUX [210]. To leverage a strong image prior, the MM-DiT

生成器从Meissonic [211],初始化,该模型经过大量训练以用于高分辨率合成。两种模态都被量化到共享的离散空间,其中预训练的VQ-VAE [32]将图像编码为码书索引,CLIP模型[22]提供文本标记的嵌入。在统一训练期间,Muddit使用余弦调度策略对令牌进行掩码,单一的MM-DiT生成器被训练去预测基于另一模态条件的干净令牌。输出方面,轻量线性头解码文本标记,而VQ-VAE解码器重构图像,从而使一组参数即可处理文本和图像的生成。

在此基础上,MMaDA [129] 将扩散范式扩展为统一的多模态基础模型。它采用LLaDA-8B-Instruct [212] 作为语言骨干网络,并使用MAGVIT-v2 [213] 图像令牌器将图像转换为离散语义令牌。这个统一的令牌空间使得生成过程中多模态条件化无缝衔接。为提升跨模态的对齐,MMaDA引入了一种混合链式思维(CoT)微调策略,将文本与视觉任务之间的推理格式统一化。该对齐促成了冷启动强化学习,使得从一开始就能进行有效的后训练。此外,MMaDA融入了一种新颖的UniGRPO方法,这是一种为扩散模型设计的统一基于策略梯度的强化学习算法。UniGRPO通过利用多样化的奖励信号(如事实正确性、视觉-文本对齐和用户偏好)来实现对推理与生成任务的后训练优化。该设计确保模型在广泛能力上持续改进,而不是过拟合于狭窄的特定任务奖励。

尽管这些创新方法不断涌现,统一离散扩散模型领域仍存在显著挑战和局限。首要问题是推理效率。尽管像 Mercury [214] 和 Gemini Diffusion [215] 这样的模型在并行生成代币方面展示了高速度潜力,但大多数开源离散扩散模型在实际推理速度上仍落后于其自回归模型对应物。这种差距主要源于对键值缓存的支持不足以及在并行解码多个令牌时输出质量的下降。扩散模型的有效性也受到训练困难的制约。与每个代币都能提供学习信号的自回归训练不同,离散扩散训练只提供稀疏监督,因为损失是在随机选择的被掩盖令牌子集上计算的,这导致对训练语料的利用效率低下且方差高。此外,这些模型表现出长度偏差,并且由于缺乏像自回归模型中序列结束令牌那样的内建停止机制,难以在不同输出长度间泛化。架构和支撑基础设施方面也需要进一步开发。在架构上,许多现有模型沿用了最初为自回归系统设计的结构,这种出于工程简化而采用的方法并不总是适合扩散过程——扩散过程旨在以根本不同于自回归模型序列性质的方式捕捉联合数据分布。在基础设施方面,对离散扩散模型的支持仍然有限。与成熟的

可用于自回归模型的框架相比,它们缺乏成熟的流水线和稳健的开源选项。这一差距阻碍了公平比较,减缓了研究进展,并使实际部署变得复杂。要推进统一离散扩散模型的能力和实际应用,必须解决这些在推理、训练、架构和基础设施方面相互关联的挑战。

3.2 自回归模型

统一多模态理解与生成模型的一个主要方向采用自回归(AR)架构,其中视觉和语言代币通常被串行化并按顺序建模。在这些模型中,主干Transformer通常改造自大型语言模型(LLMs),例如LLaMA系列[1],[2],[216],Vicuna[58],Gemma系列[217],[218],[219],和Qwen系列[5],[6],[9],[10],作为统一的模态融合模块,自回归地预测多模态输出。

如图5所示,为了将视觉信息整合到AR框架中,现有方法在模态编码期间提出了不同的图像标记化策略。这些方法大致可分为四类:基于像素、基于语义、基于可学习查询和混合编码方法。

- 基于像素的编码。如图 5(b-1) 所示,基于像素的编码通常指将图像表示为由预训练自编码器获得的连续或离散代币,这些自编码器仅通过图像重构进行监督。

构建,例如类VQGAN的模型[32],[220],[221],[222]。这些Encoder将高维像素空间压缩到紧凑的潜在空间,其中每个空间补丁对应一个图像令牌。在统一的多模态自回归模型中,从此类编码器序列化的图像令牌被以类似于文本标记的方式处理,允许

两种模态在单一序列内被建模。

最近的工作采用并通过各种编码器设计增强了基于像素的分词方法。LWM [29] 使用 VQGAN 分词器 [32] 将图像编码为离散潜在代码,而无需语义监督。它提出了一个多模态世界建模框架,其中视觉和文本代币被串行化在一起,以进行统一的自回归建模。通过仅通过基于重建的视觉代币和文本描述来学习世界动力学,LWM 表明大规模多模态生成在没有专门语义分词的情况下也是可行的。Chameleon [30] 和 ANOLE [132] 都采用了 VQ-IMG [222], ——一种为内容丰富的图像生成设计的改进型 VQ-VAE 变体。与标准 VQGAN 分词器相比,VQ-IMG 具有更深的编码器、更大的感受野,并包含残差预测以更好地保留复杂的视觉细节。该增强使 Chameleon 和 ANOLE 能更忠实地串行化图像内容,从而支持高质量的多模态生成。此外,这些模型促进了交错生成,允许在统一的自回归框架内交替生成文本和图像代币。Emu3 [133], 、SynerGen-VL [136] 和 UGen [138] 使用了 SBER-MoVQGAN [220], [221], ——一种多尺度 VQGAN 变体,将图像编码为既能捕捉全局结构又能捕捉细粒度

generator is initialized from Meissonic [211], a model extensively trained for high-resolution synthesis. Both modalities are quantized into a shared discrete space, where a pre-trained VQ-VAE [32] encodes images into codebook indices and a CLIP model [22] provides text token embeddings. During its unified training, Muddit employs a cosine scheduling strategy to mask tokens, and the single MM-DiT generator is trained to predict the clean tokens conditioned on the other modality. For output, a lightweight linear head decodes text tokens, while the VQ-VAE decoder reconstructs the image, allowing a single set of parameters to handle both text and image generation.

Building upon this foundation, MMaDA [129] scales up the diffusion paradigm toward a unified multimodal foundation model. It adopts LLaDA-8B-Instruct [212] as the language backbone and uses a MAGVIT-v2 [213] image tokenizer to convert images into discrete semantic tokens. This unified token space enables seamless multimodal conditioning during generation. To improve alignment across modalities, MMaDA introduces a mixed chain-of-thought (CoT) fine-tuning strategy, which unifies reasoning formats between text and vision tasks. This alignment facilitates cold-start reinforcement learning, allowing effective post-training from the outset. Furthermore, MMaDA incorporates a novel UniGRPO method, a unified policy-gradient-based RL algorithm designed for diffusion models. UniGRPO enables post-training optimization across both reasoning and generation tasks by leveraging diversified reward signals, such as factual correctness, visual-textual alignment, and user preferences. This design ensures the model consistently improves across a broad range of capabilities, rather than overfitting to a narrow task-specific reward.

Despite these innovative approaches, significant challenges and limitations persist in the landscape of unified discrete diffusion models. A primary concern is inference efficiency. Although models like Mercury [214] and Gemini Diffusion [215] demonstrate potential for high-speed parallel token generation, most open-source discrete diffusion models still lag behind the practical inference speeds of their autoregressive counterparts. This discrepancy is primarily due to a lack of support for key-value cache and the degradation in output quality that occurs when decoding multiple tokens in parallel. The effectiveness of diffusion models is also hindered by training difficulties. Unlike autoregressive training, where every token provides a learning signal, discrete diffusion training offers only sparse supervision, as the loss is computed on a randomly selected subset of masked tokens, leading to inefficient use of the training corpus and high variance. Moreover, these models exhibit a length bias and struggle to generalize across different output lengths because they lack a built-in stopping mechanism like the end-of-sequence token found in autoregressive models. Additional development is also needed in architecture and supporting infrastructure. Architecturally, many existing models reuse designs originally created for autoregressive systems, an approach chosen for engineering simplicity that is not always suited to the diffusion process, which aims to capture joint data distributions in a way that is fundamentally different from the sequential nature of autoregressive models. On the infrastructure side, support for discrete diffusion models remains limited. Compared to the mature

frameworks available for autoregressive models, they lack well-developed pipelines and robust open-source options. This gap hinders fair comparisons, slows research, and complicates real-world deployment. Addressing these interconnected challenges in inference, training, architecture, and infrastructure is essential to advance the capabilities and practical use of unified discrete diffusion models.

3.2 Auto-Regressive Models

One major direction in unified multimodal understanding and generation models adopts autoregressive (AR) architectures, where both vision and language tokens are typically serialized and modeled sequentially. In these models, a backbone Transformer, typically adapted from large language models (LLMs) such as LLaMA family [1], [2], [216], Vicuna [58], Gemma series [217], [218], [219], and Qwen series [5], [6], [9], [10], serves as the unified modality-fusion module to autoregressively predict multimodal outputs.

To integrate visual information into the AR framework, as shown in Fig. 5, existing methods propose different strategies for image tokenization during modality encoding. These approaches can be broadly categorized into four types: pixel-based, semantic-based, learnable query-based, hybrid-based encoding methods.

- Pixel-based Encoding. As shown in Fig. 5 (b-1), pixel-based encoding typically refers to the representation of images as continuous or discrete tokens obtained from pretrained autoencoders supervised purely by image reconstruction, such as VQGAN-like models [32], [220], [221], [222]. These encoders compress the high-dimensional pixel space into a compact latent space, where each spatial patch corresponds to an image token. In unified multimodal autoregressive models, image tokens serialized from such encoders are processed analogously to text tokens, allowing both modalities to be modeled within a single sequence.

Recent works have adopted and enhanced pixel-based tokenization with various encoder designs. LWM [29] employs a VQGAN tokenizer [32] to encode images into discrete latent codes without requiring semantic supervision. It proposes a multimodal world modeling framework, wherein visual and textual tokens are serialized together for unified autoregressive modeling. By learning world dynamics purely through reconstruction-based visual tokens and textual descriptions, LWM demonstrates that large-scale multimodal generation is feasible without specialized semantic tokenization. Both Chameleon [30] and ANOLE [132] adopt VQ-IMG [222], an improved VQ-VAE variant designed for content-rich image generation. Compared to standard VQGAN tokenizers, VQ-IMG features a deeper encoder with larger receptive fields and incorporates residual prediction to better preserve complex visual details. This enhancement enables Chameleon and ANOLE to serialize image content more faithfully, thereby supporting high-quality multimodal generation. Moreover, these models facilitate interleaved generation, allowing text and image tokens to be generated alternately within a unified autoregressive framework. Emu3 [133], SynerGen-VL [136] and UGen [138] employs SBER-MoVQGAN [220], [221], a multiscale VQGAN variant that encodes images into latent representations capturing both global structure and fine-grained

细节。通过利用多尺度分词,这些模型在保持高效训练吞吐量的同时,提高了用于自回归建模的视觉表示的表达力。与LWM [29],相似,Liquid [137]使用一种VQGAN风格的分词器,并发现了一个新见解:当在单一自回归目标和共享视觉代币表示下统一时,视觉理解与生成可以互相促进。此外,MMAR [134]、Orthus [135]、Harmon [139]引入了使用其对应编码器提取的连续值图像代币的框架,避免了与离散化相关的信息丢失。他们还通过在每个自回归图像补丁嵌入之上采用轻量级扩散头,将扩散过程与自回归骨干网络分离开来。该设计确保了骨干网络的隐藏表示不局限于最终的去噪步骤,从而促进了更好的图像理解。TokLIP[140]将低级离散VQGAN分词器与基于ViT的代币编码器SigLIP [209]集成,以捕捉高级连续语义,这不仅赋予视觉代币高级语义理解,还增强了低级生成能力。Selftok[141]提出了一种新颖的离散视觉自治分词器,在高质量重建与压缩率之间实现了良好折衷,同时为有效的视觉强化学习实现了最优策略改进。

除了MMAR[134]和Harmon[139],之外,这些模型在预训练和生成阶段都应用了因果注意力掩码,确保每个代币仅关注序列中之前的代币。它们采用下一个代币预测损失进行训练,其中图像和文本代币都以自回归方式被预测,从而统一了跨模态的训练目标。值得注意的是,在基于像素的编码方法中,用于从潜在代币重建图像的解码器通常遵循最初在类VQGAN模型中提出的配对解码器结构。这些解码器是经过专门优化的轻量级卷积架构,旨在将离散潜在网格映射回像素空间,主要关注精确的低层重建而非高级语义推理。此外,由于一些方法(例如MMAR[134],Orthus[135]和Harmon[139],)将图像标记为连续潜变量,它们采用轻量级扩散多层感知机作为解码器,将连续潜变量映射回像素空间。

尽管像素级编码方法有效,但它们存在若干固有局限:首先,由于视觉代币仅为像素级重建而优化,往往缺乏高层语义抽象,使得文本与图像表示之间的跨模态对齐更加困难。其次,基于像素的分词倾向于产生密集的代币网格,与仅文本模型相比,在高分辨率图像下会显著增加序列长度。这导致在自回归训练和推理过程中产生巨大的计算和内存开销,限制了可扩展性。第三,由于底层视觉编码器是以重建为中心的目标进行训练,所得视觉代币可能保留模态特定偏差,例如对纹理和低级模式的过度敏感,而这些并不一定有利于语义理解或精细颗粒度的跨模态推理。

- 语义编码。为克服基于像素的编码器固有的语义限制,越来越多的工作采用语义编码,即使用预训练的文本对齐视觉编码器处理图像输入,例如 OpenAI-CLIP [22]、SigLIP [209]、EVA-CLIP [36],或如 UNIT [223],这样更近的统一分词器,如图 5(b-2) 所示。其中一些模型将多模态自回归模型编码的多模态特征作为扩散模型的条件,从而在保留多模态理解能力的同时实现图像生成,例如使用 Qwen2.5-VL [10] 作为多模态模型并以增强的 OmniGen [224] 作为图像扩散模型的 OmniGen 2 [158];Ovis-U 1 [159] 通过引入定制设计的扩散 Transformer 将多模态模型 Ovis [12] 扩展为统一模型;Qwen-Image [161] 也类似地在 Qwen2.5-VL [10] 基础上集成了扩散 Transformer。然而,大多数此类模型在大规模图文对上以对比学习或回归为目标进行训练,生成的视觉嵌入在共享的语义空间中与语言特征高度对齐。这类表示能够实现更有效的跨模态对齐,对多模态理解与生成尤为有利。

若干具有代表性的模型采用不同的语义编码器和架构设计以支持统一的多模态任务。Emu [142], Emu2 [33], 和 LaViT [143]均采用 EVA-CLIP [36] 作为视觉编码器。值得注意的是,Emu [142]首次提出了将冻结的 EVA-CLIP 编码器、大型语言模型和扩散解码器结合的架构,以统一 VQA、图像描述和图像生成任务。Emu2 [33] 在 Emu [142] 的基础上提出了一个简化且可扩展的统一多模态预训练建模框架。它将 MLLM 模型规模扩展到 370 亿参数,从而显著增强了理解和生成能力。Bifrost-1 [162] 采用两个语义编码器:用于生成的 ViT 和用于理解的(在所用 MLLM(QWen2.5-VL)中使用的)编码器。预测的 CLIP 潜在表示用于连接 MLLM 与扩散模型。LaViT [143]引入了构建在 EVA-CLIP 之上的动态视觉分词机制。它使用选择器和合并器模块,基于内容复杂度自适应地从图像嵌入中选择视觉标记。该过程动态决定每张图像的视觉标记序列长度。动态分词在保留重要视觉线索的同时显著减少冗余信息,提高了训练效率和在图像描述、视觉问答及图像生成等任务中的生成质量。Dream-LLM [34], VL-GPT [35], MM-Interleaved [144], 和 PUMA [147] 均使用 OpenAI-CLIP 编码器 [22]。DreamLLM[34] 引入了一个轻量的线性投影,将 CLIP 嵌入与语言标记对齐,而 VL-GPT [35] 在 OpenAI-CLIP 视觉编码器之后采用了强大的 Casual Transformer,有效保留原始图像的语义信息和像素细节。MM-Interleaved[144] 和 PUMA [147] 都通过 CLIP 分词器结合简单的 ViT-Adapter 或池化操作提取多粒度图像特征,以提供精细的特征融合,从而支持丰富的多模态生成。Mini-Gemini [145]引入了一种需要双语义编码器的视觉标记增强机制,具体地,它利用

details. By leveraging multi-scale tokenization, these models improve the expressiveness of visual representations for autoregressive modeling while maintaining efficient training throughput. Similar with LWM [29], Liquid [137] utilizes a VQGAN-style tokenizer and uncovers a novel insight that visual understanding and generation can mutually benefit when unified under a single autoregressive objective and shared visual token representation. Moreover, MMAR [134], Orthus [135], Harmon [139] introduce the frameworks that utilize continuous-valued image tokens extracted by their corresponding encoders, avoiding the information loss associated with discretization. They also decouple the diffusion process from the AR backbone by employing lightweight diffusion heads atop each auto-regressed image patch embedding. This design ensures that the backbone’s hidden representations are not confined to the final denoising step, facilitating better image understanding. TokLIP [140] integrates a low-level discrete VQGAN tokenizer with a ViT-based token encoder SigLIP [209] to capture high-level continuous semantics, which not only empowers visual tokens with high-level semantic understanding but also enhances low-level generative capacity. Selftok [141] introduces a novel discrete visual self-consistency tokenizer, achieving a favorable trade-off between high-quality reconstruction and compression rate while enabling optimal policy improvement for effective visual reinforcement learning.