paper阅读:Improving Language Understanding by Generative Pre-Training

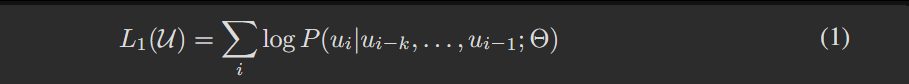

公式L1U∑ilogPui∣ui−kui−1;Θ定义了无监督预训练阶段的语言模型目标函数,通过最大化每个词元在其前kkk个词元上下文条件下的对数概率之和,来训练神经网络模型Θ\ThetaΘ。这本质上是在最小化整个语料库的负对数似然,促使模型学习如何根据历史信息准确预测下一个词,从而捕获语言的内在结构和模式。

《Improving Language Understanding by Generative Pre-Training》是 GPT-1 的核心论文,聚焦于通过生成式预训练提升自然语言理解能力。

太长速看版:

论文核心内容总结

本文提出了一套“生成式预训练+判别式微调”的框架,通过单一与任务无关的Transformer模型实现高性能自然语言理解(NLU),核心目标是借助无监督预训练提升各类有监督判别式任务的性能。

一、核心方法设计

-

预训练阶段:采用BooksCorpus数据集(含7000+本未出版书籍,涵盖多题材大段连续文本)训练仅含解码器的12层Transformer模型,重点习得世界知识与长距离依赖处理能力;对比1B Word Benchmark,强调连续文本对保留长距离结构的重要性,最终模型在该语料上实现18.4的低标记级困惑度。

-

微调阶段:沿用预训练超参数,针对不同任务设计结构化输入转换策略(如NLI任务拼接前提与假设、相似度任务包含两种句子顺序、问答任务拼接上下文-问题-候选答案),并添加丢弃率0.1的分类器;多数任务采用6.25e-5学习率、32批次大小,仅需3个epoch即可收敛,同时采用带预热的线性学习率衰减策略。

-

零样本与消融实验设计:设计启发式方案探究模型零样本表现,验证预训练对任务相关功能的学习作用;通过三项消融实验(移除辅助LM目标、替换为LSTM、移除预训练),验证各组件的必要性。

二、实验表现与关键发现

-

多任务评估结果:在自然语言推理(NLI)、问答、语义相似度、文本分类四大类12个数据集上开展实验,9个数据集取得新最优结果。其中,QNLI提升5.8%、SciTail提升5%、Story Cloze提升8.9%、RACE提升5.7%;在GLUE基准测试集上获72.8的综合得分,显著优于此前68.9的最优结果。

-

数据集适配性:模型在不同规模数据集上均表现稳定,从小型数据集STS-B(≈5.7k训练样本)到大型数据集SNLI(≈550k训练样本)均能有效适配,验证了方法的泛化能力。

-

组件有效性验证:消融实验表明:预训练是性能核心(移除后全任务平均下降14.8%);Transformer架构优于LSTM(替换后平均得分降5.6分);语言模型辅助目标对大规模数据集增益显著,小规模数据集无明显受益;迁移全部预训练层效果最优(MultiNLI最大提升9%)。

-

零样本表现:启发式方案在无监督微调下可完成多任务,性能随预训练进程稳定提升;Transformer零样本性能波动小于LSTM,证明其架构归纳偏置更利于迁移。

三、核心贡献与意义

-

验证了“无监督预训练+有监督微调”在NLU任务上的有效性,实现显著性能突破,达成机器学习领域长期以来“用无监督学习提升判别式任务性能”的重要目标。

-

指明适配该方法的最优模型(Transformer)与数据集类型(含长距离依赖的连续文本),为后续研究提供方向。

-

推动自然语言理解及其他领域的无监督学习研究,助力深化对无监督学习适用场景与作用机制的理解。

精读版:

Improving Language Understanding by Generative Pre-Training 通过生成式预训练提升语言理解能力

Abstract摘要

Natural language understanding comprises a wide range of diverse tasks such as textual entailment, question answering, semantic similarity assessment, and document classification.自然语言理解涵盖多种不同的任务,例如文本蕴涵、问答、语义相似度评估以及文档分类。

Although large unlabeled text corpora are abundant, labeled data for learning these specific tasks is scarce, making it challenging for discriminatively trained models to perform adequately.尽管大规模未标注文本语料库数量充足,但用于学习这些特定任务的标注数据却十分稀缺,这使得判别式训练的模型难以取得理想的性能表现。

We demonstrate that large gains on these tasks can be realized by generative pre-training of a language model on a diverse corpus of unlabeled text, followed by discriminative fine-tuning on each specific task.我们证明,先在多样化的未标注文本语料库上对语言模型进行生成式预训练,再在各个特定任务上进行判别式微调,就能在这些任务上实现显著的性能提升。

In contrast to previous approaches, we make use of task-aware input transformations during fine-tuning to achieve effective transfer while requiring minimal changes to the model architecture.与以往的方法不同,我们在微调阶段采用任务感知的输入转换策略,在仅对模型架构进行最小化修改的前提下,实现高效的知识迁移。

We demonstrate the effectiveness of our approach on a wide range of benchmarks for natural language understanding.我们在多个自然语言理解基准任务上,验证了该方法的有效性。

Our general task-agnostic model outperforms discriminatively trained models that use architectures specifically crafted for each task, significantly improving upon the state of the art in 9 out of the 12 tasks studied.我们所提出的通用型任务无关模型,性能优于那些为各任务量身定制架构的判别式训练模型,在研究涉及的 12 项任务中,有 9 项的性能显著刷新了当时的最优水平。

For instance, we achieve absolute improvements of 8.9% on commonsense reasoning (Stories Cloze Test), 5.7% on question answering (RACE), and 1.5% on textual entailment (MultiNLI).例如,在常识推理任务(故事完形填空)上,我们取得了 8.9% 的绝对性能提升;在问答任务(RACE 数据集)上提升了 5.7%;在文本蕴涵任务(MultiNLI 数据集)上提升了 1.5%。

Introduction介绍

The ability to learn effectively from raw text is crucial to alleviating the dependence on supervised learning in natural language processing (NLP).从原始文本中高效学习的能力,对于减轻自然语言处理(NLP)领域对监督学习的依赖至关重要。

Most deep learning methods require substantial amounts of manually labeled data, which restricts their applicability in many domains that suffer from a dearth of annotated resources [61].大多数深度学习方法需要大量人工标注数据,这限制了它们在许多缺乏标注资源的领域中的适用性 [61]。

In these situations, models that can leverage linguistic information from unlabeled data provide a valuable alternative to gathering more annotation, which can be time-consuming and expensive.在这类情况下,能够利用未标注数据中的语言信息的模型,为获取更多标注(标注过程既耗时又昂贵)提供了一种有价值的替代方案。

Further, even in cases where considerable supervision is available, learning good representations in an unsupervised fashion can provide a significant performance boost.此外,即便在有大量监督数据可用的情况下,通过无监督方式学习优质表征,仍能为模型带来显著的性能提升。

The most compelling evidence for this so far has been the extensive use of pre-trained word embeddings [10 , 39 , 42] to improve performance on a range of NLP tasks [ 8, 11 , 26 , 45].迄今为止,支持这一观点的最有力证据是:预训练词嵌入 [10, 39, 42] 被广泛应用于提升一系列 NLP 任务 [8, 11, 26, 45] 的性能。

Leveraging more than word-level information from unlabeled text, however, is challenging for two main reasons.然而,要从无标注文本中获取超出单词层面的信息,仍面临两大挑战。

First, it is unclear what type of optimization objectives are most effective at learning text representations that are useful for transfer.首先,目前尚不清楚哪种类型的优化目标,在学习可用于迁移的文本表征方面最为有效。

Recent research has looked at various objectives such as language modeling [44], machine translation [ 38 ], and discourse coherence [22 ], with each method outperforming the others on different tasks.近期研究探讨了多种目标,例如语言建模 [44]、机器翻译 [38] 和语篇连贯性 [22],且每种方法在不同任务上的表现均优于其他方法。

Second, there is no consensus on the most effective way to transfer these learned representations to the target task.其次,对于将这些已学习到的表征迁移到目标任务的最有效方式,目前尚未达成共识。

Existing techniques involve a combination of making task-specific changes to the model architecture [43 , 44], using intricate learning schemes [21 ] and adding auxiliary learning objectives [ 50].现有技术通常结合了多种方式:对模型架构进行任务特定修改 [43, 44]、采用复杂的学习方案 [21],以及添加辅助学习目标 [50]。

These uncertainties have made it difficult to develop effective semi-supervised learning approaches for language processing.这些不确定性导致人们难以开发出用于语言处理的有效半监督学习方法。

In this paper, we explore a semi-supervised approach for language understanding tasks using a combination of unsupervised pre-training and supervised fine-tuning.

在本文中,我们探索了一种半监督方法用于语言理解任务,该方法结合了无监督预训练与有监督微调。

Our goal is to learn a universal representation that transfers with little adaptation to a wide range of tasks.

我们的目标是学习一种通用表征,该表征仅需少量适配即可迁移到各类任务中。

We assume access to a large corpus of unlabeled text and several datasets with manually annotated training examples (target tasks).

我们假设可获取一个大规模未标注文本语料库,以及多个包含人工标注训练样本的数据集(即目标任务数据集)。

Our setup does not require these target tasks to be in the same domain as the unlabeled corpus.

我们的实验设置不要求这些目标任务与未标注语料库处于同一领域。

We employ a two-stage training procedure.

我们采用两阶段训练流程。

First, we use a language modeling objective on the unlabeled data to learn the initial parameters of a neural network model.

第一阶段,我们在未标注数据上以语言建模为目标,学习神经网络模型的初始参数。

Subsequently, we adapt these parameters to a target task using the corresponding supervised objective.

随后,我们利用相应的有监督目标,将这些参数适配到特定目标任务中。

For our model architecture, we use the Transformer [62], which has been shown to perform strongly on various tasks such as machine translation [ 62 ], document generation [34 ], and syntactic parsing [29].在模型架构方面,我们采用 Transformer [62]—— 该架构已被证明在机器翻译 [62]、文档生成 [34]、句法分析 [29] 等多种任务中表现出色。

This model choice provides us with a more structured memory for handling long-term dependencies in text, compared to alternatives like recurrent networks, resulting in robust transfer performance across diverse tasks.与循环神经网络等其他架构相比,选择该模型能为我们提供更具结构性的记忆机制,以处理文本中的长期依赖关系,进而在各类任务中实现稳定的迁移性能。

During transfer, we utilize task-specific input adaptations derived from traversal-style approaches [52], which process structured text input as a single contiguous sequence of tokens.在迁移过程中,我们采用基于遍历式方法 [52] 设计的任务特定输入适配方案,该方案会将结构化文本输入处理为单个连续的标记序列。

As we demonstrate in our experiments, these adaptations enable us to fine-tune effectively with minimal changes to the architecture of the pre-trained model.正如我们在实验中所证明的,此类适配方案使我们能够在对预训练模型架构进行最小化修改的前提下,高效完成微调过程。

We evaluate our approach on four types of language understanding tasks – natural language inference, question answering, semantic similarity, and text classification.我们在四类语言理解任务上对所提方法进行评估,分别是自然语言推理、问答、语义相似度判定和文本分类。

Our general task-agnostic model outperforms discriminatively trained models that employ architectures specifically crafted for each task, significantly improving upon the state of the art in 9 out of the 12 tasks studied.我们提出的通用型任务无关模型,性能优于那些为各任务量身设计架构的判别式训练模型,在研究所涉及的 12 项任务中,有 9 项显著刷新了当时的最优水平(SOTA)。

For instance, we achieve absolute improvements of 8.9% on commonsense reasoning (Stories Cloze Test) [40 ], 5.7% on question answering (RACE) [ 30 ], 1.5% on textual entailment (MultiNLI) [ 66 ] and 5.5% on the recently introduced GLUE multi-task benchmark [64 ].例如,在常识推理任务(故事完形填空测试,Stories Cloze Test)[40] 上,我们实现了 8.9% 的绝对性能提升;在问答任务(RACE 数据集)[30] 上提升 5.7%;在文本蕴涵任务(MultiNLI 数据集)[66] 上提升 1.5%;在近期提出的 GLUE 多任务基准测试 [64] 上提升 5.5%。

We also analyzed zero-shot behaviors of the pre-trained model on four different settings and demonstrate that it acquires useful linguistic knowledge for downstream tasks.我们还在四种不同设置下分析了预训练模型的零样本(zero-shot)表现,结果表明该模型已习得对下游任务有用的语言知识。

We evaluate our approach on four types of language understanding tasks – natural language inference, question answering, semantic similarity, and text classification.我们在四类语言理解任务上对所提方法进行评估,分别是自然语言推理、问答、语义相似度判定和文本分类。

Our general task-agnostic model outperforms discriminatively trained models that employ architectures specifically crafted for each task, significantly improving upon the state of the art in 9 out of the 12 tasks studied.我们提出的通用型任务无关模型,性能优于那些为各任务量身设计架构的判别式训练模型,在研究所涉及的 12 项任务中,有 9 项显著刷新了当时的最优水平(SOTA)。

For instance, we achieve absolute improvements of 8.9% on commonsense reasoning (Stories Cloze Test) [40 ], 5.7% on question answering (RACE) [ 30 ], 1.5% on textual entailment (MultiNLI) [ 66 ] and 5.5% on the recently introduced GLUE multi-task benchmark [64 ].例如,在常识推理任务(故事完形填空测试,Stories Cloze Test)[40] 上,我们实现了 8.9% 的绝对性能提升;在问答任务(RACE 数据集)[30] 上提升 5.7%;在文本蕴涵任务(MultiNLI 数据集)[66] 上提升 1.5%;在近期提出的 GLUE 多任务基准测试 [64] 上提升 5.5%。

We also analyzed zero-shot behaviors of the pre-trained model on four different settings and demonstrate that it acquires useful linguistic knowledge for downstream tasks.我们还在四种不同设置下分析了预训练模型的零样本(zero-shot)表现,结果表明该模型已习得对下游任务有用的语言知识。

2 Related Work相关工作

Semi-supervised learning for NLP Our work broadly falls under the category of semi-supervised learning for natural language.自然语言处理领域的半监督学习:我们的研究工作大致归属于自然语言半监督学习这一范畴。

This paradigm has attracted significant interest, with applications to tasks like sequence labeling [24, 33, 57] or text classification [41 , 70 ].该范式已引起广泛关注,并被应用于序列标注 [24, 33, 57]、文本分类 [41, 70] 等任务中。

The earliest approaches used unlabeled data to compute word-level or phrase-level statistics, which were then used as features in a supervised model [33].早期的方法利用未标注数据计算单词层面或短语层面的统计信息,随后将这些信息作为特征用于监督模型中 [33]。

Over the last few years, researchers have demonstrated the benefits of using word embeddings [11 , 39 , 42], which are trained on unlabeled corpora, to improve performance on a variety of tasks [8, 11 , 26 , 45 ].过去几年间,研究人员已证实:使用在未标注语料库上训练得到的词嵌入 [11, 39, 42],有助于提升多种任务 [8, 11, 26, 45] 的性能。

These approaches, however, mainly transfer word-level information, whereas we aim to capture higher-level semantics.然而,这些方法主要迁移的是单词层面的信息,而我们的目标是捕捉更高层面的语义信息。

Recent approaches have investigated learning and utilizing more than word-level semantics from unlabeled data.近期的研究方法已开始探索从无标注数据中学习并利用超出单词层面的语义信息。

Phrase-level or sentence-level embeddings, which can be trained using an unlabeled corpus, have been used to encode text into suitable vector representations for various target tasks [28, 32, 1, 36, 22, 12, 56, 31].短语层面或句子层面的嵌入(可通过无标注语料库训练得到),已被用于将文本编码为适用于各类目标任务的向量表征 [28, 32, 1, 36, 22, 12, 56, 31]。

Unsupervised pre-training Unsupervised pre-training is a special case of semi-supervised learning where the goal is to find a good initialization point instead of modifying the supervised learning objective.

无监督预训练:无监督预训练是半监督学习的一种特殊情况,其目标是找到一个良好的初始化点,而非修改监督学习的目标函数。

Early works explored the use of the technique in image classification [ 20 , 49 , 63 ] and regression tasks [ 3].

早期研究探索了该技术在图像分类[20, 49, 63]和回归任务[3]中的应用。

Subsequent research [ 15 ] demonstrated that pre-training acts as a regularization scheme, enabling better generalization in deep neural networks.

后续研究[15]表明,预训练可起到正则化作用,能提升深度神经网络的泛化能力。

In recent work, the method has been used to help train deep neural networks on various tasks like image classification [69 ], speech recognition [68], entity disambiguation [17] and machine translation [48].

在近期研究中,该方法已被用于辅助训练深度神经网络完成各类任务,例如图像分类[69]、语音识别[68]、实体消歧[17]以及机器翻译[48]。

The closest line of work to ours involves pre-training a neural network using a language modeling objective and then fine-tuning it on a target task with supervision.与我们研究最相近的工作方向,是先以语言建模为目标对神经网络进行预训练,再在有监督的条件下针对目标任务对其进行微调。

Dai et al. [13] and Howard and Ruder [21] follow this method to improve text classification.Dai 等人 [13] 以及 Howard 与 Ruder [21] 均采用该方法来提升文本分类任务的性能。

However, although the pre-training phase helps capture some linguistic information, their usage of LSTM models restricts their prediction ability to a short range.然而,尽管预训练阶段有助于捕捉部分语言信息,但他们所使用的 LSTM 模型,将自身的预测能力限制在了较短的文本范围内。

In contrast, our choice of transformer networks allows us to capture longer-range linguistic structure, as demonstrated in our experiments.与之相反,正如我们在实验中所证明的,我们选择的 Transformer 网络能够捕捉更长范围的语言结构。

Further, we also demonstrate the effectiveness of our model on a wider range of tasks including natural language inference, paraphrase detection and story completion.此外,我们还在更广泛的任务上验证了模型的有效性,这些任务包括自然语言推理、复述检测和故事补全。

Other approaches [43 , 44 , 38] use hidden representations from a pre-trained language or machine translation model as auxiliary features while training a supervised model on the target task.其他方法 [43, 44, 38] 在针对目标任务训练监督模型时,会将预训练语言模型或机器翻译模型的隐藏层表征用作辅助特征。

This involves a substantial amount of new parameters for each separate target task, whereas we require minimal changes to our model architecture during transfer.这种方式需要为每个独立的目标任务新增大量参数,而我们在模型迁移过程中,仅需对模型架构进行最小化修改。

Auxiliary training objectives Adding auxiliary unsupervised training objectives is an alternative form of semi-supervised learning.辅助训练目标:添加辅助无监督训练目标是半监督学习的一种替代形式。

Early work by Collobert and Weston [10] used a wide variety of auxiliary NLP tasks such as POS tagging, chunking, named entity recognition, and language modeling to improve semantic role labeling.Collobert 与 Weston 的早期研究 [10] 采用了多种自然语言处理辅助任务(如词性标注、分块、命名实体识别和语言建模),以提升语义角色标注任务的性能。

More recently, Rei [50] added an auxiliary language modeling objective to their target task objective and demonstrated performance gains on sequence labeling tasks.近期,Rei [50] 在其目标任务目标函数中加入了辅助语言建模目标,并证明该方法能提升序列标注任务的性能。

Our experiments also use an auxiliary objective, but as we show, unsupervised pre-training already learns several linguistic aspects relevant to target tasks.我们的实验同样使用了辅助目标,但正如我们所证明的,无监督预训练本身已能学习到与目标任务相关的多个语言层面信息。

3 Framework

3框架

Our training procedure consists of two stages.

我们的训练流程包含两个阶段。

The first stage is learning a high-capacity language model on a large corpus of text.

第一阶段是在大规模文本语料库上训练一个高容量语言模型。

This is followed by a fine-tuning stage, where we adapt the model to a discriminative task with labeled data.

随后是微调阶段,在此阶段我们利用标注数据将模型适配到判别式任务中。

3.1 Unsupervised pre-training

3.1 无监督预训练

Given an unsupervised corpus of tokens U = {u1, . . . , un}, we use a standard language modeling objective to maximize the following likelihood:

给定一个由标记构成的无监督语料库U = {u₁, …, uₙ},我们采用标准的语言建模目标函数,以最大化以下概率:

(注:公式中“u₁, …, uₙ”表示语料库中按序列排列的单个标记,“likelihood”在统计学与机器学习语境中译为“概率”,此处特指语言模型对文本序列预测的概率值,后续若需补充该公式的完整表达式及推导过程翻译,可提供完整公式文本,确保数学符号与学术表述的一致性。)

【公式含义】:

该公式定义了在无监督预训练阶段,语言模型优化的负对数似然损失函数。其核心目的是通过最大化语料库中每个词的条件概率(给定其前k个词),来学习文本的生成模式,从而使模型能够预测序列中的下一个词。

【符号解释】:

- L1(U)L_1(U)L1(U):表示在无监督语料库 UUU 上计算的语言模型损失函数,通常是负对数似然。最小化此损失等同于最大化语料的似然。

- U={u1,…,un}U = \{u_1, \dots, u_n\}U={u1,…,un}:表示一个无监督的文本语料库,其中包含 nnn 个词元(tokens)。

- ∑i\sum_{i}∑i:表示对语料库中所有词元 uiu_iui 进行求和。

- log\loglog:表示自然对数。

- P(ui∣ui−k,…,ui−1;Θ)P(u_i | u_{i-k}, \dots, u_{i-1}; \Theta)P(ui∣ui−k,…,ui−1;Θ):表示在给定前 kkk 个词元 ui−k,…,ui−1u_{i-k}, \dots, u_{i-1}ui−k,…,ui−1 的条件下,当前词元 uiu_iui 出现的条件概率。这个概率是由一个参数为 Θ\ThetaΘ 的神经网络模型计算得出的。

- kkk:表示上下文窗口的大小,即用于预测当前词元的历史词元数量。

- Θ\ThetaΘ:表示神经网络模型的参数集合,这些参数通过随机梯度下降进行训练。

【公式解释】:

该公式不是一个推导公式,而是一个目标函数(Objective Function),用于衡量语言模型在无监督学习阶段的性能,并通过优化它来训练模型。

背景知识:语言模型与最大似然估计

在自然语言处理中,**语言模型(Language Model)**的任务是计算一个词序列的概率。它通常通过预测序列中的下一个词来学习语言的统计规律。例如,给定“我喜欢吃”,语言模型会预测下一个词是“苹果”、“香蕉”或“饭”等。

**最大似然估计(Maximum Likelihood Estimation, MLE)**是一种常用的参数估计方法,其核心思想是:给定一组观测数据,选择能够使这组数据出现的概率最大的模型参数。在语言模型中,这意味着我们希望调整模型参数 Θ\ThetaΘ,使得整个训练语料 UUU 出现的概率最大化。

公式的应用场景和工作原理:

-

目标:最大化语料库的联合概率

一个语言模型的目标是最大化整个无监督语料库 U={u1,…,un}U = \{u_1, \dots, u_n\}U={u1,…,un} 的联合概率 P(U;Θ)P(U; \Theta)P(U;Θ)。根据链式法则,这个联合概率可以分解为:

P(U;Θ)=P(u1;Θ)×P(u2∣u1;Θ)×⋯×P(un∣u1,…,un−1;Θ)P(U; \Theta) = P(u_1; \Theta) \times P(u_2 | u_1; \Theta) \times \dots \times P(u_n | u_1, \dots, u_{n-1}; \Theta)P(U;Θ)=P(u1;Θ)×P(u2∣u1;Θ)×⋯×P(un∣u1,…,un−1;Θ)

或者更一般地写成:

P(U;Θ)=∏i=1nP(ui∣u1,…,ui−1;Θ)P(U; \Theta) = \prod_{i=1}^{n} P(u_i | u_1, \dots, u_{i-1}; \Theta)P(U;Θ)=∏i=1nP(ui∣u1,…,ui−1;Θ) -

引入上下文窗口 kkk

在实际操作中,让模型考虑整个历史序列来预测下一个词是计算量巨大的。因此,通常会引入一个上下文窗口 kkk,让模型只考虑前 kkk 个词来预测当前词。这样,上述条件概率 P(ui∣u1,…,ui−1;Θ)P(u_i | u_1, \dots, u_{i-1}; \Theta)P(ui∣u1,…,ui−1;Θ) 就近似为 P(ui∣ui−k,…,ui−1;Θ)P(u_i | u_{i-k}, \dots, u_{i-1}; \Theta)P(ui∣ui−k,…,ui−1;Θ)。 -

对数似然与损失函数

为了方便计算和优化(特别是避免数值下溢和将乘积转换为求和),我们通常最大化对数似然(Log-Likelihood)。对数函数是单调递增的,因此最大化似然等同于最大化对数似然:

logP(U;Θ)=log(∏i=1nP(ui∣ui−k,…,ui−1;Θ))\log P(U; \Theta) = \log \left( \prod_{i=1}^{n} P(u_i | u_{i-k}, \dots, u_{i-1}; \Theta) \right)logP(U;Θ)=log(∏i=1nP(ui∣ui−k,…,ui−1;Θ))

根据对数性质 log(AB)=logA+logB\log(AB) = \log A + \log Blog(AB)=logA+logB,上式变为:

logP(U;Θ)=∑i=1nlogP(ui∣ui−k,…,ui−1;Θ)\log P(U; \Theta) = \sum_{i=1}^{n} \log P(u_i | u_{i-k}, \dots, u_{i-1}; \Theta)logP(U;Θ)=∑i=1nlogP(ui∣ui−k,…,ui−1;Θ)这个求和项 ∑ilogP(ui∣ui−k,…,ui−1;Θ)\sum_{i} \log P(u_i | u_{i-k}, \dots, u_{i-1}; \Theta)∑ilogP(ui∣ui−k,…,ui−1;Θ) 就是公式 (1) 的右侧部分,它代表了给定模型参数 Θ\ThetaΘ 时,整个语料库 UUU 的对数似然。

-

负对数似然作为损失函数

在机器学习中,我们通常使用损失函数(Loss Function)并通过梯度下降等优化算法来最小化它。最大化对数似然等同于最小化负对数似然(Negative Log-Likelihood, NLL)。因此,公式 (1) 中的 L1(U)L_1(U)L1(U) 就是负对数似然损失,即:

L1(U)=−∑ilogP(ui∣ui−k,…,ui−1;Θ)L_1(U) = - \sum_{i} \log P(u_i | u_{i-k}, \dots, u_{i-1}; \Theta)L1(U)=−∑ilogP(ui∣ui−k,…,ui−1;Θ)论文中给出的公式 (1) 实际上就是这个负对数似然损失,但去掉了负号,因为在上下文“最大化以下似然”中,直接给出对数似然的形式是常见的。在实际训练中,优化器会最小化这个表达式的负值。

示例:

假设我们有一个无监督语料库 U="The cat sat on the mat."U = \text{{"The cat sat on the mat."}}U="The cat sat on the mat.",上下文窗口 k=2k=2k=2。

当模型预测 ui="sat"u_i = \text{"sat"}ui="sat" 时,它会根据前两个词 ui−2="The"u_{i-2}=\text{"The"}ui−2="The" 和 ui−1="cat"u_{i-1}=\text{"cat"}ui−1="cat" 来计算 P("sat"∣"The","cat";Θ)P(\text{"sat"} | \text{"The"}, \text{"cat"}; \Theta)P("sat"∣"The","cat";Θ)。

然后,当模型预测 ui="on"u_i = \text{"on"}ui="on" 时,它会根据前两个词 ui−2="cat"u_{i-2}=\text{"cat"}ui−2="cat" 和 ui−1="sat"u_{i-1}=\text{"sat"}ui−1="sat" 来计算 P("on"∣"cat","sat";Θ)P(\text{"on"} | \text{"cat"}, \text{"sat"}; \Theta)P("on"∣"cat","sat";Θ)。

公式 L1(U)L_1(U)L1(U) 就是将语料库中所有词元的这些条件对数概率相加(并取负号进行最小化),以衡量模型对整个语料库的预测准确性。

【总结】:

公式 L1(U)=∑ilogP(ui∣ui−k,…,ui−1;Θ)L_1(U) = \sum_{i} \log P(u_i | u_{i-k}, \dots, u_{i-1}; \Theta)L1(U)=∑ilogP(ui∣ui−k,…,ui−1;Θ) 定义了无监督预训练阶段的语言模型目标函数,通过最大化每个词元在其前 kkk 个词元上下文条件下的对数概率之和,来训练神经网络模型 Θ\ThetaΘ。这本质上是在最小化整个语料库的负对数似然,促使模型学习如何根据历史信息准确预测下一个词,从而捕获语言的内在结构和模式。

where k is the size of the context window, and the conditional probability P is modeled using a neural network with parameters Θ. These parameters are trained using stochastic gradient descent [51].其中,k 表示上下文窗口的大小,条件概率 P 由一个参数为 Θ 的神经网络建模。这些参数通过随机梯度下降法 [51] 进行训练。

(注:“context window” 为 NLP 领域核心术语,译为 “上下文窗口”,指模型在预测当前标记时所参考的前后标记范围;“stochastic gradient descent” 简称 SGD,标准译法为 “随机梯度下降法”,是深度学习中常用的参数优化算法;符号 “Θ” 在机器学习中通常统一表示模型的所有可训练参数集合,此处保留原符号以符合学术表达习惯。)

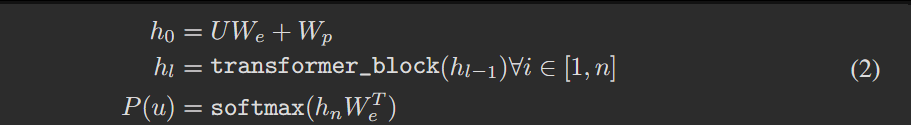

In our experiments, we use a multi-layer Transformer decoder [34] for the language model, which is a variant of the transformer [62]. This model applies a multi-headed self-attention operation over the input context tokens followed by position-wise feedforward layers to produce an output distribution over target tokens:在我们的实验中,语言模型采用多层 Transformer 解码器 [34],该解码器是 Transformer [62] 的一个变体。该模型首先对输入上下文标记执行多头自注意力操作,随后通过按位置排列的前馈层,生成目标标记的输出分布:

(注:“multi-layer Transformer decoder” 译为 “多层 Transformer 解码器”,明确模型结构层级与功能定位;“multi-headed self-attention” 是 Transformer 核心机制,标准译法为 “多头自注意力”,指通过多个并行注意力头捕捉文本不同维度的关联信息;“position-wise feedforward layers” 译为 “按位置排列的前馈层”,强调该层对每个标记的位置信息单独处理;“output distribution over target tokens” 译为 “目标标记的输出分布”,对应语言模型预测每个候选标记概率的核心输出形式。)

where U = (u−k, . . . , u−1) is the context vector of tokens, n is the number of layers, We is the token embedding matrix, and Wp is the position embedding matrix.

其中,U = (u₋ₖ, …, u₋₁) 表示标记的上下文向量,n 为网络层数,We 为标记嵌入矩阵,Wp 为位置嵌入矩阵。

(注:1. 符号“u₋ₖ, …, u₋₁”表示上下文窗口中从“第 -k 个标记”到“第 -1 个标记”的序列,负号用于区分“上下文标记”与待预测的“当前标记”,符合语言模型中“基于历史上下文预测未来token”的逻辑;2. “token embedding matrix”(标记嵌入矩阵)和“position embedding matrix”(位置嵌入矩阵)是Transformer模型的核心组件,前者将离散标记映射为连续向量,后者注入文本的位置信息,二者均为NLP领域固定译法,确保学术表述一致性。)

3.2 Supervised fine-tuning

3.2 监督式微调

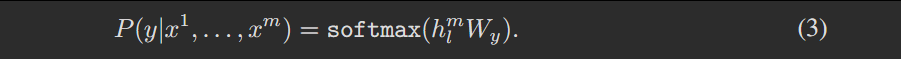

After training the model with the objective in Eq. 1, we adapt the parameters to the supervised target task. We assume a labeled dataset C, where each instance consists of a sequence of input tokens, x₁, …, xₘ, along with a label y. The inputs are passed through our pre-trained model to obtain the final transformer block’s activation hᵐˡ, which is then fed into an added linear output layer with parameters Wᵧ to predict y:

使用公式1(Eq. 1)中的目标函数训练模型后,我们将模型参数适配到有监督目标任务中。我们假设存在一个标注数据集C,其中每个样本包含一个输入标记序列x₁, …, xₘ,以及对应的标签y。将输入传入预训练模型后,可得到Transformer最后一个模块的激活值hᵐˡ;随后将该激活值输入新增的、参数为Wᵧ的线性输出层,以实现对y的预测:

(注:1. “Eq. 1”为学术论文中“公式1”的标准缩写,保留原符号以符合学术格式习惯;2. 符号“x₁, …, xₘ”表示目标任务中单个样本的输入标记序列,m为该序列的长度;3. “activation hᵐˡ”译为“激活值hᵐˡ”,其中上标“ml”通常对应“multi-layer”(多层)或“final layer”(最后一层),特指Transformer模型最后一个模块输出的特征表示;4. “linear output layer”(线性输出层)是适配判别式任务的核心组件,通过参数矩阵Wᵧ将模型学到的特征映射到标签空间,实现分类或回归预测。)

【公式含义】:

该公式定义了在有监督微调阶段,预训练模型如何针对特定任务预测给定输入序列 x1,…,xmx^1, \dots, x^mx1,…,xm 对应的标签 yyy 的概率。它描述了模型通过将Transformer最后一层的激活值 hlmh_l^mhlm 映射到一个线性输出层,并经过Softmax函数,来计算最终的类别概率。

【符号解释】:

- P(y∣x1,…,xm)P(y|x^1, \dots, x^m)P(y∣x1,…,xm):表示在给定输入序列 x1,…,xmx^1, \dots, x^mx1,…,xm 的情况下,预测标签 yyy 的概率。这是模型在有监督任务中的输出目标。

- x1,…,xmx^1, \dots, x^mx1,…,xm:表示一个输入序列的词元。在有监督任务中,这通常是需要模型进行分类、推理或问答的文本输入。

- yyy:表示与输入序列 x1,…,xmx^1, \dots, x^mx1,…,xm 相关的真实标签。例如,在文本分类任务中,这可能是“正面”或“负面”情感;在问答任务中,这可能是正确答案的索引。

- softmax(⋅)\text{softmax}(\cdot)softmax(⋅):表示Softmax激活函数。它将一个实数向量(通常是模型最后一层输出的“logit”值)转换成一个概率分布,使得所有元素的和为1,且每个元素都在0到1之间。这使得模型可以输出各个类别的概率。

- hlmh_l^mhlm:表示预训练Transformer模型中最后一层 Transformer 块(即第 lll 层)的最终激活值。具体来说,这个 hlmh_l^mhlm 是通过将输入序列 x1,…,xmx^1, \dots, x^mx1,…,xm 传递给预训练模型后,从模型的最后一层获得的,它代表了整个输入序列的聚合语义表示。这里的 mmm 通常表示输入序列的最后一个词元对应的隐藏状态,或者是对整个序列进行某种池化(如平均池化或最大池化)后的表示。根据论文上下文,它更倾向于是指整个输入序列的最终表示。

- WyW_yWy:表示线性输出层的参数矩阵。这是一个新添加的、针对特定有监督任务训练的权重矩阵。它将Transformer模型输出的隐藏表示 hlmh_l^mhlm 映射到与任务类别数量相对应的维度空间。

【公式解释】:

该公式不是一个推导公式,而是描述了 Transformer 模型在有监督微调阶段如何进行最终的预测。它建立在模型已经完成无监督预训练,并学习了通用语言表示的基础上。

背景知识:

在本文提出的两阶段训练过程(无监督预训练和有监督微调)中,此公式属于第二阶段——有监督微调。

- 无监督预训练:模型(一个多层Transformer解码器)首先在一个大规模的无标签文本语料库上进行语言模型任务的预训练(如在公式(1)中描述的,最大化下一个词元的预测似然)。这个阶段的目的是让模型学习到丰富的语言知识和通用的文本表示能力。

- 有监督微调:在预训练完成后,模型的参数被初始化为预训练阶段学到的值。然后,针对特定的下游任务(如文本分类、问答等),模型在一个小规模的标注数据集上进行微调。此时,模型的架构会添加一个任务特定的输出层,并且整个模型(或部分层)的参数会根据有监督任务的损失函数进行更新。

公式应用场景和计算流程:

这个公式描述了在有监督微调阶段,对于给定的一个输入序列 [x1,…,xm][x^1, \dots, x^m][x1,…,xm],模型如何计算其对应标签 yyy 的预测概率。

-

获取输入序列的最终表示 hlmh_l^mhlm:

- 首先,将有监督任务的输入序列 [x1,…,xm][x^1, \dots, x^m][x1,…,xm] 传递给已经预训练好的Transformer模型。

- Transformer模型按照其内部机制(词元嵌入、位置嵌入、多头自注意力、前馈网络、残差连接和层归一化)处理这个序列。

- 最终,从Transformer模型的最后一层获取一个聚合的隐藏状态表示 hlmh_l^mhlm。这个 hlmh_l^mhlm 捕获了输入序列的深层语义和上下文信息。在分类任务中,这通常是序列中最后一个词元的隐藏状态,或者对所有词元隐藏状态进行某种池化(例如平均池化或最大池化)后的向量,以作为整个序列的表示。

-

通过线性输出层进行映射 hlmWyh_l^m W_yhlmWy:

- 获取到的序列表示 hlmh_l^mhlm 会被送入一个新添加的线性输出层。

- 这个线性层通过与参数矩阵 WyW_yWy 相乘,将 hlmh_l^mhlm 映射到一个新的向量空间。这个新向量的维度通常与当前任务的类别数量相匹配。例如,如果是一个二分类任务,该向量可能有两个元素,分别代表两个类别的“得分”或“logit”。

- WyW_yWy 是在微调阶段新初始化并学习的参数,它是模型针对特定任务进行预测的关键组成部分。

-

通过Softmax函数计算概率分布 softmax(hlmWy)\text{softmax}(h_l^m W_y)softmax(hlmWy):

- 线性层输出的得分向量会经过Softmax函数。

- Softmax函数将这些得分转换为一个概率分布,确保所有类别的预测概率之和为1。

- 每个元素 P(yi∣x1,…,xm)P(y_i|x^1, \dots, x^m)P(yi∣x1,…,xm) 表示输入序列属于第 iii 个类别的概率。模型最终会选择概率最高的类别作为预测结果。

具体应用示例:

假设我们有一个情感分类任务,输入序列是一个电影评论 “This movie is fantastic.”,标签 yyy 可能是“正面”或“负面”。

- 输入:评论 “This movie is fantastic.” 被词元化为 [x1,x2,x3,x4][x^1, x^2, x^3, x^4][x1,x2,x3,x4]。

- Transformer处理:这些词元被送入预训练的Transformer模型。模型处理后,从最后一层提取出代表整个评论的隐藏状态 hlmh_l^mhlm。

- 线性层: hlmh_l^mhlm 乘以新添加的线性层权重 WyW_yWy。假设这是一个二分类任务, WyW_yWy 会将 hlmh_l^mhlm 映射成一个2维向量,例如 [score正面,score负面]=[2.5,−1.0][ \text{score}_{\text{正面}}, \text{score}_{\text{负面}} ] = [2.5, -1.0][score正面,score负面]=[2.5,−1.0]。

- Softmax:Softmax函数将 [2.5,−1.0][2.5, -1.0][2.5,−1.0] 转换为概率分布,例如 P(正面∣评论)=0.95P(\text{正面}| \text{评论}) = 0.95P(正面∣评论)=0.95,P(负面∣评论)=0.05P(\text{负面}| \text{评论}) = 0.05P(负面∣评论)=0.05。模型最终预测该评论为“正面”。

【总结】:

该公式清晰地阐述了在有监督微调阶段,预训练Transformer模型如何通过一个新添加的线性输出层和Softmax函数,将输入文本序列的深层隐藏表示 hlmh_l^mhlm 转化为特定任务的类别概率 P(y∣x1,…,xm)P(y|x^1, \dots, x^m)P(y∣x1,…,xm)。这使得通用语言模型能够被有效适应到各种下游判别性任务中。

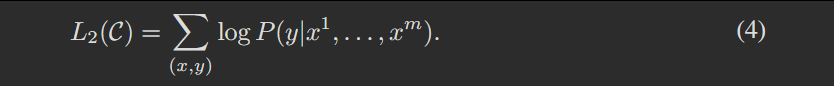

This gives us the following objective to maximize:

这使我们得到以下需要最大化的目标:

【公式含义】:

该公式定义了在有监督微调阶段用于训练模型的核心目标函数。它表示通过最大化所有标注数据集中,模型对每个输入序列 x1,…,xmx^1, \dots, x^mx1,…,xm 预测其正确标签 yyy 的对数似然之和。

【符号解释】:

- L2(C)L_2(C)L2(C):表示针对有监督任务 CCC 的损失函数(或目标函数)。在机器学习中,我们通常最大化似然或最小化损失。这里的 L2(C)L_2(C)L2(C) 是一个需要最大化的对数似然函数。

- ∑(x,y)\sum_{(x,y)}∑(x,y):表示对数据集 CCC 中所有(输入序列,标签)对进行求和。

- (x,y)(x,y)(x,y):代表数据集 CCC 中的一个样本,其中 xxx 是一个输入序列(由词元 x1,…,xmx^1, \dots, x^mx1,…,xm 组成),yyy 是与该输入序列对应的真实标签。

- logP(y∣x1,…,xm)\log P(y|x^1, \dots, x^m)logP(y∣x1,…,xm):表示在给定输入序列 x1,…,xmx^1, \dots, x^mx1,…,xm 的情况下,预测其真实标签 yyy 的对数概率。

- P(y∣x1,…,xm)P(y|x^1, \dots, x^m)P(y∣x1,…,xm):如前一个公式所述,这是模型通过Transformer和线性-Softmax层计算出的,给定输入序列预测正确标签 yyy 的概率。

- log(⋅)\log(\cdot)log(⋅):自然对数函数。使用对数概率作为目标函数(即对数似然)是机器学习中的标准做法,因为它将乘积转化为和,简化了计算,并且在优化时通常表现更好(例如,避免梯度消失/爆炸)。

【公式解释】:

该公式不是一个推导公式,而是直接定义了有监督微调阶段的核心优化目标。

背景知识:

在机器学习,特别是分类任务中,模型的目标是学习从输入到输出标签的映射。在有监督学习中,我们拥有带有正确标签的训练数据。一个常见的优化策略是最大似然估计(Maximum Likelihood Estimation, MLE),即调整模型参数,使得模型在给定训练数据时,观测到这些数据的概率最大。对于分类任务,这意味着最大化模型对每个训练样本预测其真实标签的概率。

公式应用场景和计算流程:

这个公式 L2(C)=∑(x,y)∈ClogP(y∣x1,…,xm)L_2(C) = \sum_{(x,y) \in C} \log P(y|x^1, \dots, x^m)L2(C)=∑(x,y)∈ClogP(y∣x1,…,xm) 定义了在微调阶段,模型通过**交叉熵损失(或负对数似然)**来衡量其预测与真实标签之间的差距,并以此为目标进行优化。由于这里是最大化对数似然,它等价于最小化负对数似然(也就是交叉熵损失)。

-

数据准备:

- 假设我们有一个有监督的标注数据集 CCC,其中包含多个 (输入序列 xxx, 真实标签 yyy) 对。

- 例如,在一个情感分类任务中,数据集中可能包含:

- (“This movie is fantastic.”, “Positive”)

- (“It was quite boring.”, “Negative”)

- …

-

单样本对数概率计算:

- 对于数据集 CCC 中的每一个样本 (x,y)(x, y)(x,y):

- 模型会首先接收输入序列 xxx (即 x1,…,xmx^1, \dots, x^mx1,…,xm)。

- 然后,通过预训练的Transformer模型(如前所述,它生成了输入序列的隐藏表示 hlmh_l^mhlm),接着通过一个新添加的线性输出层和Softmax函数,计算出该输入序列属于各个类别的概率分布 P(⋅∣x1,…,xm)P(\cdot|x^1, \dots, x^m)P(⋅∣x1,…,xm)。

- 从这个概率分布中,我们取出对应真实标签 yyy 的概率 P(y∣x1,…,xm)P(y|x^1, \dots, x^m)P(y∣x1,…,xm)。

- 最后,计算这个概率的对数 logP(y∣x1,…,xm)\log P(y|x^1, \dots, x^m)logP(y∣x1,…,xm)。这个值越大,说明模型预测 yyy 的概率越高,其表现越好。

- 对于数据集 CCC 中的每一个样本 (x,y)(x, y)(x,y):

-

求和:

- 将所有样本的 logP(y∣x1,…,xm)\log P(y|x^1, \dots, x^m)logP(y∣x1,…,xm) 值累加起来。

- 这个总和 L2(C)L_2(C)L2(C) 就是模型在整个有监督数据集 CCC 上的总对数似然。

-

优化目标:

- 在微调过程中,模型会使用梯度下降等优化算法来调整其参数(包括预训练Transformer的参数和新添加的线性层的参数),以最大化这个 L2(C)L_2(C)L2(C) 值。

- 通过最大化总对数似然,模型被训练得能够更准确地预测训练数据中的真实标签。

与公式(3)的关系:

公式(3) P(y∣x1,...,xm)=softmax(hlmWy)P(y|x^1,...,xm) = \text{softmax}(h_l^m W_y)P(y∣x1,...,xm)=softmax(hlmWy) 描述了模型如何计算单个样本的预测概率 P(y∣x1,…,xm)P(y|x^1, \dots, x^m)P(y∣x1,…,xm)。

而公式(4) L2(C)=∑(x,y)logP(y∣x1,…,xm)L_2(C) = \sum_{(x,y)} \log P(y|x^1, \dots, x^m)L2(C)=∑(x,y)logP(y∣x1,…,xm) 则是将这些单个样本的对数概率求和,构建成整个有监督数据集上的总对数似然目标函数。在训练过程中,模型会努力最大化这个总对数似然,从而学习到更好的参数来完成有监督任务。

【总结】:

公式(4) L2(C)L_2(C)L2(C) 是在生成式预训练(GPT)模型的有监督微调阶段所使用的核心目标函数。它通过累加数据集中所有样本的正确标签对数概率,来衡量模型在当前任务上的表现,并指导模型参数的优化方向,以实现对真实标签的更准确预测。

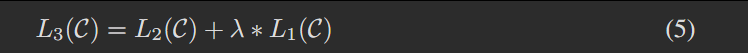

We additionally found that including language modeling as an auxiliary objective to the fine-tuning helped learning by (a) improving generalization of the supervised model, and (b) accelerating convergence. This is in line with prior work [50, 43], who also observed improved performance with such an auxiliary objective. Specifically, we optimize the following objective (with weight λ):我们还发现,在微调阶段将语言建模作为辅助目标,可通过以下两方面助力模型学习:(a)提升监督模型的泛化能力;(b)加快模型收敛速度。这与以往研究 [50, 43] 的结论一致,这些研究也观察到此类辅助目标能带来性能提升。具体而言,我们优化的目标函数如下(含权重 λ):

(注:1. “auxiliary objective” 为机器学习领域固定术语,译为 “辅助目标”,指在主任务目标之外额外添加的、用于辅助模型学习的优化目标;2. “generalization” 译为 “泛化能力”,指模型对未见过的新数据的适应能力;“convergence” 译为 “收敛速度”,指模型参数迭代至稳定最优值的快慢;3. 符号 “λ”(lambda)为目标函数中辅助目标的权重系数,用于平衡主任务目标与辅助目标的贡献,保留原符号符合学术表达规范。)

【公式含义】:

该公式定义了在预训练模型进行有监督微调时所使用的最终优化目标,它结合了监督任务的对数似然和语言模型的对数似然作为辅助目标。其核心目的是通过引入语言模型目标,改善模型的泛化能力并加速收敛。

【符号解释】:

- L3(C)L_3(C)L3(C):表示最终的优化目标函数。这是在有监督微调阶段,模型实际要最大化的联合对数似然。

- L2(C)L_2(C)L2(C):表示监督任务的对数似然。如前文公式(4)所述,它衡量模型在给定输入序列 x1,…,xmx^1, \dots, x^mx1,…,xm 时,预测其真实标签 yyy 的对数概率之和。

- CCC:指代有监督的标注数据集。

- λ\lambdaλ:表示辅助语言模型目标 L1(C)L_1(C)L1(C) 的权重(或超参数)。它是一个标量,用于平衡监督任务目标和辅助语言模型目标的重要性。

- 根据论文描述,

λ在实验中被设置为0.5。

- 根据论文描述,

- L1(C)L_1(C)L1(C):表示辅助语言模型(LM)目标。尽管 L1L_1L1 最初是在无监督预训练阶段用于最大化在无标注语料 UUU 上的语言模型似然(如公式(1)所示),但在微调阶段,它作为辅助目标被应用于有监督数据集 CCC。这意味着模型在预测监督任务标签的同时,也尝试最大化其对监督数据集 CCC 中每个词元序列的对数概率。

【公式解释】:

这个公式不是一个推导公式,而是定义了在有监督微调阶段所采用的联合优化目标。它将传统的监督学习目标与预训练阶段的语言模型目标结合起来。

背景知识:

- 最大似然估计 (MLE):在机器学习中,我们通常希望模型参数能够使得训练数据出现的概率最大化。对于分类任务,这意味着最大化模型预测正确标签的概率。对数似然是最大化概率的常用方式,因为对数函数是单调递增的,且能将乘积转化为和,便于计算。

- 辅助任务 (Auxiliary Tasks):在深度学习中,辅助任务是指除了主任务之外,额外训练的一些任务。这些任务通常与主任务相关,可以帮助模型学习到对主任务有用的通用表示或特性。通过多任务学习(Multi-task Learning),主任务和辅助任务共享模型的一部分参数,从而实现知识迁移和模型泛化能力的提升。

- 语言模型 (Language Modeling):语言模型旨在预测序列中下一个词的概率,或者评估一个词序列的概率。预训练语言模型能够捕获丰富的语法和语义信息。

公式的应用场景和计算流程:

论文提到,在微调阶段,额外引入语言模型作为辅助目标,有助于:

- 提高监督模型的泛化能力 (improving generalization of the supervised model):通过继续训练语言模型,模型能够更好地保持和利用在预训练阶段学到的通用语言知识,避免在特定任务上过拟合。

- 加速收敛 (accelerating convergence):语言模型提供了一个额外的、持续的梯度信号,这可以帮助模型更快地找到最优解。

因此,为了实现这些好处,模型在微调时不再仅仅最大化 L2(C)L_2(C)L2(C)(监督任务似然),而是最大化一个结合了 L2(C)L_2(C)L2(C) 和 L1(C)L_1(C)L1(C)(辅助语言模型似然)的加权和 L3(C)L_3(C)L3(C)。

具体计算流程:

在每次微调迭代中:

-

计算监督任务对数似然 L2(C)L_2(C)L2(C):

- 从有监督数据集 CCC 中取一个批次的样本 (x,y)(x,y)(x,y)。

- 将输入序列 xxx 喂给Transformer模型,得到最终的隐藏表示 hlmh_l^mhlm。

- 通过线性输出层和Softmax,计算预测标签的概率分布 P(⋅∣x1,…,xm)P(\cdot|x^1, \dots, x^m)P(⋅∣x1,…,xm)。

- 计算该批次样本的真实标签 yyy 对应的对数概率之和,即 ∑logP(y∣x1,…,xm)\sum \log P(y|x^1, \dots, x^m)∑logP(y∣x1,…,xm)。

-

计算辅助语言模型对数似然 L1(C)L_1(C)L1(C):

- 使用与步骤1相同的输入序列 xxx(或同一批次的文本数据)。

- 让模型像在预训练阶段一样,计算每个词元给定其前文的对数概率之和,即 ∑ilogP(ui∣ui−k,…,ui−1;Θ)\sum_{i} \log P(u_i|u_{i-k}, \dots, u_{i-1}; \Theta)∑ilogP(ui∣ui−k,…,ui−1;Θ)。这里,uiu_iui 是输入序列 xxx 中的词元。注意,尽管符号 L1(C)L_1(C)L1(C) 中的 CCC 指的是有监督数据集,但计算方式与公式(1)描述的语言模型目标完全一致,即预测序列中的下一个词元。

-

计算最终目标 L3(C)L_3(C)L3(C):

- 将 L2(C)L_2(C)L2(C) 与乘以权重 λ\lambdaλ 的 L1(C)L_1(C)L1(C) 相加:L3(C)=L2(C)+λ∗L1(C)L_3(C) = L_2(C) + \lambda * L_1(C)L3(C)=L2(C)+λ∗L1(C)。

-

模型参数更新:

- 优化器(如Adam)会根据最大化 L3(C)L_3(C)L3(C) 的目标来调整模型的所有可训练参数(包括Transformer的参数和新添加的线性层的参数)。

- 这意味着模型参数的更新方向,既要让模型在监督任务上表现好,又要让模型在语言建模任务上表现好,从而保持其通用语言理解能力。

这种联合优化方法,使得模型在学习特定任务知识的同时,不会“遗忘”其作为语言模型所学到的通用语言规律,从而在小样本或复杂任务上表现出更好的鲁赖性和泛化性。

【总结】:

公式(5) L3(C)=L2(C)+λ∗L1(C)L_3(C) = L_2(C) + \lambda * L_1(C)L3(C)=L2(C)+λ∗L1(C) 是GPT模型在有监督微调阶段的最终优化目标。它通过结合监督任务的对数似然 L2(C)L_2(C)L2(C) 和加权辅助语言模型对数似然 λ∗L1(C)\lambda * L_1(C)λ∗L1(C),旨在同时提升模型的泛化能力和训练收敛速度,确保模型在适应特定任务的同时,能继续利用其在预训练阶段学到的丰富语言知识。

Overall, the only extra parameters we require during fine-tuning are Wy, and embeddings for delimiter tokens (described below in Section 3.3).

总体而言,我们在微调阶段所需的额外参数仅有两部分:一是(用于预测标签的)参数矩阵Wy,二是分隔符标记的嵌入向量(下文3.3节将对此进行说明)。

(注:1. “extra parameters”译为“额外参数”,特指在预训练模型参数基础上,为适配目标任务新增的参数,与前文“最小化修改模型架构”的核心设计一致;2. “delimiter tokens”译为“分隔符标记”,是NLP任务中用于区分输入文本不同部分(如问答任务中的“问题”与“上下文”)的特殊标记,其嵌入向量需在微调阶段学习,以适配任务特定的输入结构;3. “Section 3.3”保留英文章节编号格式,符合学术论文引用习惯,明确后续说明的位置。)

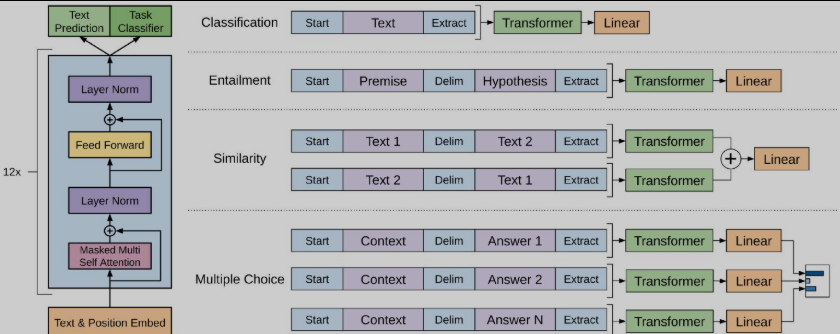

Figure 1: (left) Transformer architecture and training objectives used in this work. (right) Input transformations for fine-tuning on different tasks. We convert all structured inputs into token sequences to be processed by our pre-trained model, followed by a linear+softmax layer.

图1:(左)本文中使用的Transformer架构和训练目标。(右)针对不同任务进行微调的输入转换。我们将所有结构化输入转换为token序列,以便由我们的预训练模型处理,然后是一个线性+softmax层。

3.3 Task-specific input transformations

3.3 针对特定任务的输入转换

-

For some tasks, like text classification, we can directly fine-tune our model as described above.

对于部分任务(如文本分类),我们可按照上述方式直接对模型进行微调。 -

Certain other tasks, like question answering or textual entailment, have structured inputs such as ordered sentence pairs, or triplets of document, question, and answers.

而其他一些任务(如问答或文本蕴涵)则具有结构化输入,例如有序句子对,或“文档-问题-答案”三元组。 -

Since our pre-trained model was trained on contiguous sequences of text, we require some modifications to apply it to these tasks.

由于我们的预训练模型是在连续文本序列上训练的,因此要将其应用于这些任务,需要进行一些调整。 -

Previous work proposed learning task specific architectures on top of transferred representations [44].

以往研究[44]提出在迁移表征的基础上,学习特定于任务的架构。 -

Such an approach re-introduces a significant amount of task-specific customization and does not use transfer learning for these additional architectural components.

这种方法会重新引入大量任务特定的定制化工作,且对于这些额外的架构组件,并未采用迁移学习的方式(即需重新训练)。 -

Instead, we use a traversal-style approach [52], where we convert structured inputs into an ordered sequence that our pre-trained model can process.

与之相反,我们采用遍历式方法[52]:将结构化输入转换为预训练模型可处理的有序序列。 -

These input transformations allow us to avoid making extensive changes to the architecture across tasks.

通过这些输入转换,我们无需在不同任务间对模型架构进行大量修改。 -

We provide a brief description of these input transformations below and Figure 1 provides a visual illustration.

下文将简要介绍这些输入转换,图1则提供了可视化示意图。 -

All transformations include adding randomly initialized start and end tokens (⟨s⟩, ⟨e⟩).

所有转换均包含添加随机初始化的起始标记(⟨s⟩)和结束标记(⟨e⟩)。

(注:1. “structured inputs”译为“结构化输入”,特指非连续文本序列的任务输入格式,与预训练的“连续文本序列”形成对比;2. “traversal-style approach”译为“遍历式方法”,是将非连续结构转换为连续序列的核心策略,保留“遍历”以体现对结构化输入各部分的完整覆盖;3. 标记“⟨s⟩”“⟨e⟩”为任务通用的序列边界标记,保留原符号以符合学术论文中符号使用规范,“randomly initialized”强调其初始参数随机生成,需在微调中适配任务。)

Similarity For similarity tasks, there is no inherent ordering of the two sentences being compared.语义相似度任务:对于语义相似度任务,待比较的两个句子不存在固有的顺序关系。To reflect this, we modify the input sequence to contain both possible sentence orderings (with a delimiter in between) and process each independently to produce two sequence representations (h^m_l) which are added element-wise before being fed into the linear output layer.为体现这一特点,我们对输入序列进行调整,使其包含两种可能的句子排列顺序(顺序之间用分隔符隔开);随后对两种排列的序列分别独立处理,得到两个序列表征(h^m_l);在将其输入线性输出层之前,先对这两个表征执行按元素相加操作。(注:1. “similarity tasks” 译为语义相似度任务,该任务的核心是衡量两个文本语义的相近程度,与句子顺序无关;2. “inherent ordering” 译为固有的顺序关系,强调句子先后排列不影响语义相似度的判定逻辑;3. “element-wise” 译为按元素相加,是深度学习中张量运算的常用表述,指两个维度相同的向量或矩阵对应位置的元素分别相加。

-

Question Answering and Commonsense Reasoning For these tasks, we are given a context document zzz, a question qqq, and a set of possible answers {ak}\{a_k\}{ak}.

问答与常识推理任务:对于这类任务,模型的输入包含一个上下文文档zzz、一个问题qqq,以及一组候选答案{ak}\{a_k\}{ak}。 -

We concatenate the document context and question with each possible answer, adding a delimiter token in between to get $[z; q; $; a_k].我们将上下文文档、问题与每个候选答案进行拼接,各部分之间添加分隔符标记,得到拼接序列. 我们将上下文文档、问题与每个候选答案进行拼接,各部分之间添加分隔符标记,得到拼接序列.我们将上下文文档、问题与每个候选答案进行拼接,各部分之间添加分隔符标记,得到拼接序列[z; q; $; a_k]$。

-

Each of these sequences are processed independently with our model and then normalized via a softmax layer to produce an output distribution over possible answers.

模型对每个拼接序列进行独立处理,再通过softmax层完成归一化,最终生成候选答案的输出概率分布。

(注:1. “Commonsense Reasoning”译为常识推理,是NLP领域的典型任务,要求模型结合常识知识完成推理;2. 拼接序列$[z; q; $; a_k]$保留原符号格式,分号用于区分不同输入单元,符合学术论文的序列表示规范;3. “softmax layer”译为softmax层,其核心作用是将模型输出的原始得分转换为概率分布,实现候选答案的概率归一化。)

4 Experiments

4 实验

4.1 Setup

4.1 设置

Unsupervised pre-training We use the BooksCorpus dataset [71] for training the language model.

无监督预训练:我们采用BooksCorpus数据集[71]训练语言模型。

It contains over 7,000 unique unpublished books from a variety of genres including Adventure, Fantasy, and Romance.

该数据集包含7000多本独特的未出版书籍,涵盖冒险、奇幻、浪漫等多种题材。

Crucially, it contains long stretches of contiguous text, which allows the generative model to learn to condition on long-range information.

关键在于,数据集内包含大段连续文本,这使得生成式模型能够学习基于长距离信息进行预测。

An alternative dataset, the 1B Word Benchmark, which is used by a similar approach, ELMo [44], is approximately the same size but is shuffled at a sentence level - destroying long-range structure.

另一个可供选择的数据集是10亿词基准数据集,类似方法ELMo[44]曾采用该数据集;其规模与BooksCorpus大致相当,但数据在句子层面被打乱,破坏了文本的长距离结构。

Our language model achieves a very low token level perplexity of 18.4 on this corpus.

我们的语言模型在该数据集上取得了极低的标记级困惑度,数值仅为18.4。

(注:1. “BooksCorpus”“1B Word Benchmark”“ELMo”为专有名词,保留原名称;2. “long stretches of contiguous text”译为大段连续文本,强调文本的连贯性,这是模型学习长距离依赖的关键前提;3. “perplexity”译为困惑度,是语言模型的核心评估指标,数值越低代表模型对文本的预测能力越强。)

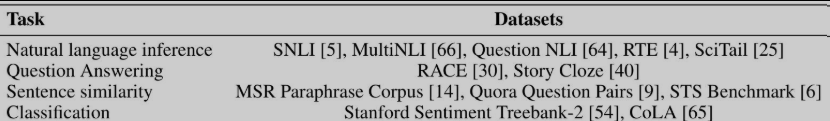

Table 1: A list of the different tasks and datasets used in our experiments.

表1:实验中使用的不同任务和数据集列表。

Model specifications Our model largely follows the original transformer work [62].

模型规格:我们的模型在很大程度上沿用了Transformer的原始设计方案[62]。

We trained a 12-layer decoder-only transformer with masked self-attention heads (768 dimensional states and 12 attention heads).

我们训练了一个仅包含解码器的12层Transformer模型,该模型采用掩码自注意力机制,其状态维度为768,注意力头数量为12。

For the position-wise feed-forward networks, we used 3072 dimensional inner states.

对于按位置前馈网络,我们设置的内部状态维度为3072。

We used the Adam optimization scheme [27] with a max learning rate of 2.5e-4.

优化器采用Adam算法[27],最大学习率设置为2.5×10⁻⁴。

The learning rate was increased linearly from zero over the first 2000 updates and annealed to 0 using a cosine schedule.

学习率在前2000次参数更新中从零开始线性递增,之后采用余弦退火策略衰减至0。

We train for 100 epochs on minibatches of 64 randomly sampled, contiguous sequences of 512 tokens.

模型训练共进行100个轮次,每个批次包含64个随机采样的连续标记序列,序列长度均为512个标记。

Since layernorm [2] is used extensively throughout the model, a simple weight initialization of N (0, 0.02) was sufficient.

由于模型中广泛使用了层归一化技术[2],因此采用简单的正态分布初始化方式N(0,0.02)N(0,0.02)N(0,0.02)即可满足需求。

We used a bytepair encoding (BPE) vocabulary with 40,000 merges [53] and residual, embedding, and attention dropouts with a rate of 0.1 for regularization.

我们采用字节对编码(BPE)构建词表,词表合并次数为40000次[53];同时在残差连接、嵌入层和注意力层均设置了丢弃率为0.1的Dropout,以此实现正则化。

We also employed a modified version of L2 regularization proposed in [37], with w = 0.01 on all non bias or gain weights.

此外,我们还采用了文献[37]提出的改进型L2正则化方法,对所有非偏置、非增益权重设置的正则化系数w=0.01w=0.01w=0.01。

For the activation function, we used the Gaussian Error Linear Unit (GELU) [18].

激活函数选用高斯误差线性单元(GELU)[18]。

We used learned position embeddings instead of the sinusoidal version proposed in the original work.

位置嵌入采用可学习的方式,而非原始Transformer中提出的正弦位置嵌入方式。

We use the ftfy library² to clean the raw text in BooksCorpus, standardize some punctuation and whitespace, and use the spaCy tokenizer.³

我们使用ftfy库²对BooksCorpus数据集中的原始文本进行清洗,标准化部分标点符号与空白字符,并采用spaCy分词器³完成分词操作。

(注:1. “cosine schedule”译为余弦退火策略,是深度学习中常用的学习率衰减方法;2. “bytepair encoding (BPE)”译为字节对编码,是NLP领域常用的子词分词算法;3. 上标数字²、³为论文中的引用标注,保留原格式以符合学术规范。)

Fine-tuning details Unless specified, we reuse the hyperparameter settings from unsupervised pre-training.

微调细节:除非另有说明,否则我们直接沿用无监督预训练阶段的超参数设置。

We add dropout to the classifier with a rate of 0.1.

我们在分类器中加入丢弃率为0.1的Dropout层。

For most tasks, we use a learning rate of 6.25e-5 and a batchsize of 32.

对于大多数任务,我们采用的学习率为6.25×10⁻⁵,批次大小为32。

Our model finetunes quickly and 3 epochs of training was sufficient for most cases.

我们的模型微调速度较快,在大多数情况下,仅需训练3个轮次即可达到理想效果。

We use a linear learning rate decay schedule with warmup over 0.2% of training.

我们采用带预热的线性学习率衰减策略,预热阶段占总训练步数的0.2%。

λ\lambdaλ was set to 0.5.

超参数λ\lambdaλ的取值被设置为0.5。

(注:1. dropout rate译为丢弃率,是正则化的常用手段,用于防止模型过拟合;2. learning rate decay schedule with warmup译为带预热的学习率衰减策略,预热可避免训练初期学习率过大导致模型不稳定;3. 符号λ\lambdaλ对应前文辅助目标函数的权重系数,此处明确其具体取值。)

4.2 Supervised fine-tuning

4.2 监督式微调

We perform experiments on a variety of supervised tasks including natural language inference, question answering, semantic similarity, and text classification.

我们在多种监督任务上开展实验,包括自然语言推理、问答、语义相似度计算以及文本分类。

Some of these tasks are available as part of the recently released GLUE multi-task benchmark [64], which we make use of.

其中部分任务来自于近期发布的GLUE多任务基准测试集[64],本研究采用了该基准测试集。

Figure 1 provides an overview of all the tasks and datasets.

图1对所有任务及对应的数据集进行了整体介绍。

(注:1. GLUE 全称为 General Language Understanding Evaluation,是自然语言处理领域常用的多任务基准测试集,用于评估模型的通用语言理解能力,保留原缩写符合学术惯例;2. “multi-task benchmark”译为多任务基准测试集,强调其包含多种不同类型的NLP任务,可综合衡量模型性能。)

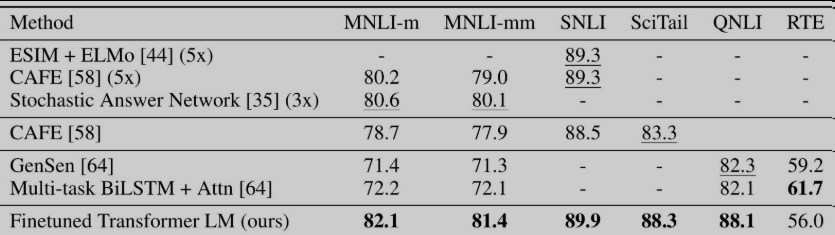

Natural Language Inference The task of natural language inference (NLI), also known as recognizing textual entailment, involves reading a pair of sentences and judging the relationship between them from one of entailment, contradiction or neutral.自然语言推理任务:自然语言推理(NLI),也被称为识别文本蕴涵,其任务内容为读取一对句子,并判断二者之间的关系属于蕴涵、矛盾或中立这三类之一。

Although there has been a lot of recent interest [58, 35, 44], the task remains challenging due to the presence of a wide variety of phenomena like lexical entailment, coreference, and lexical and syntactic ambiguity.尽管该任务近期已受到诸多关注 [58, 35, 44],但由于存在词汇蕴涵、指代消解以及词汇与句法歧义等多种语言现象,它依然具有较高的挑战性。

We evaluate on five datasets with diverse sources, including image captions (SNLI), transcribed speech, popular fiction, and government reports (MNLI), Wikipedia articles (QNLI), science exams (SciTail) or news articles (RTE).我们在五个来源各异的数据集上进行评估,这些数据集的来源包括图像描述(SNLI)、语音转写文本、通俗小说与政府报告(MNLI)、维基百科条目(QNLI)、科学考试题目(SciTail)以及新闻文章(RTE)。

(注:1. lexical entailment 译为词汇蕴涵,指词汇层面的语义包含关系;coreference 译为指代消解,是 NLP 领域的基础任务,旨在确定文本中代词与所指对象的对应关系;2. SNLI、MNLI、QNLI、SciTail、RTE 均为自然语言推理领域的经典数据集,保留原缩写符合学术表述习惯;3. 各数据集后的括号标注明确了其数据来源,便于区分不同数据集的特性。)

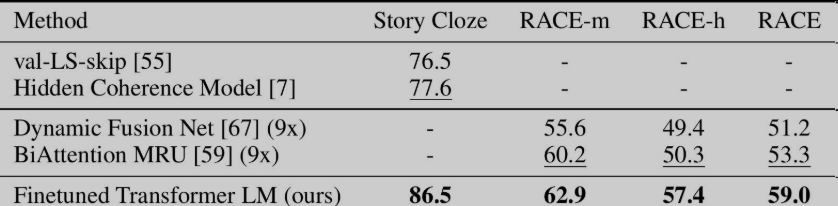

Question answering and commonsense reasoning Another task that requires aspects of single and multi-sentence reasoning is question answering.

问答与常识推理:另一项需要单句及多句推理能力的任务是问答任务。

We use the recently released RACE dataset [30], consisting of English passages with associated questions from middle and high school exams.

我们采用了近期发布的RACE数据集[30],该数据集包含取自初高中英语考试的阅读篇章及配套题目。

This corpus has been shown to contain more reasoning type questions that other datasets like CNN [19] or SQuaD [47], providing the perfect evaluation for our model which is trained to handle long-range contexts.

研究表明,与CNN[19]、SQuaD[47]等其他数据集相比,该语料库包含更多推理类题目,恰好可以用来评估我们这个专为处理长距离上下文而训练的模型。

In addition, we evaluate on the Story Cloze Test [40], which involves selecting the correct ending to multi-sentence stories from two options.

此外,我们还在故事补全测试数据集(Story Cloze Test)[40]上进行了评估,该任务要求从两个选项中选出多句故事的正确结尾。

On these tasks, our model again outperforms the previous best results by significant margins - up to 8.9% on Story Cloze, and 5.7% overall on RACE.

在这两项任务上,我们的模型再次以显著优势超越此前的最优结果——在故事补全测试上性能提升幅度最高达8.9%,在RACE数据集上的整体性能提升幅度达5.7%。

This demonstrates the ability of our model to handle long-range contexts effectively.

这证明了我们的模型具备高效处理长距离上下文的能力。

(注:1. commonsense reasoning 译为常识推理,指模型结合日常知识完成文本推理的能力;2. RACE dataset 是源于考试真题的问答数据集,侧重推理类题目,保留原名称;3. significant margins 译为显著优势,强调模型性能提升的幅度具有统计学意义;4. long-range contexts 译为长距离上下文,是本文模型的核心优势,指捕捉文本中跨度较大的语义关联。)

Table 2: Experimental results on natural language inference tasks, comparing our model with current state-of-the-art methods. 5x indicates an ensemble of 5 models. All datasets use accuracy as the evaluation metric.

表2:自然语言推理任务的实验结果,将我们的模型与当前最先进的方法进行比较。5x表示5个模型的集成。所有数据集都使用准确率作为评估指标。

Table 3: Results on question answering and commonsense reasoning, comparing our model with current state-of-the-art methods. . 9x means an ensemble of 9 models.

表 3:在问答和常识推理方面的结果,将我们的模型与当前最先进的方法进行比较。. 9x 表示 9 个模型的集成。

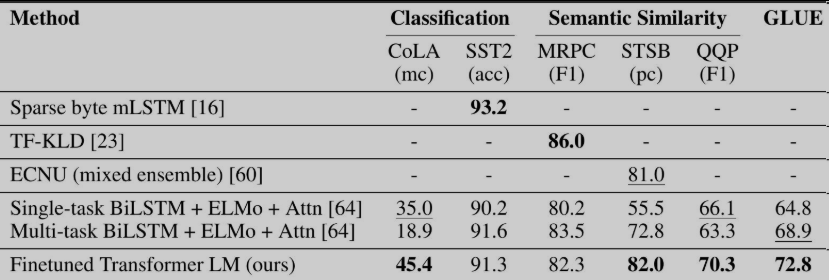

Semantic Similarity Semantic similarity (or paraphrase detection) tasks involve predicting whether two sentences are semantically equivalent or not.

语义相似度:语义相似度(或称释义检测)任务的核心是判断两个句子在语义上是否等价。

The challenges lie in recognizing rephrasing of concepts, understanding negation, and handling syntactic ambiguity.

该任务的难点在于识别概念的不同表述方式、理解否定语义,以及处理句法歧义问题。

We use three datasets for this task – the Microsoft Paraphrase corpus (MRPC) [14] (collected from news sources), the Quora Question Pairs (QQP) dataset [9], and the Semantic Textual Similarity benchmark (STS-B) [6].

我们在该任务中使用了三个数据集,分别是微软释义语料库(MRPC)[14](数据来源于新闻文本)、Quora问题对数据集(QQP)[9],以及语义文本相似度基准测试集(STS-B)[6]。

We obtain state-of-the-art results on two of the three semantic similarity tasks (Table 4) with a 1 point absolute gain on STS-B.

我们在三项语义相似度任务中的两项上取得了最优结果(见表4),其中在STS-B数据集上实现了1个百分点的绝对性能提升。

The performance delta on QQP is significant, with a 4.2% absolute improvement over Single-task BiLSTM + ELMo + Attn.

模型在QQP数据集上的性能提升幅度十分显著,相较于单任务双向长短期记忆网络+ELMo+注意力机制模型,实现了4.2%的绝对性能提升。

(注:1. paraphrase detection 译为释义检测,是语义相似度任务的常见表述,特指判断两个句子是否为同义改写;2. performance delta 译为性能提升幅度,是学术论文中描述模型性能差异的常用表达;3. Single-task BiLSTM + ELMo + Attn 为对比模型的完整结构名称,保留原格式以符合学术表述规范,其中Attn为Attention(注意力机制)的缩写。)

Classification Finally, we also evaluate on two different text classification tasks.文本分类任务:最后,我们还在两项不同的文本分类任务上进行了评估。

The Corpus of Linguistic Acceptability (CoLA) [65] contains expert judgements on whether a sentence is grammatical or not, and tests the innate linguistic bias of trained models.语言可接受性语料库(CoLA)[65] 包含了专家对句子是否符合语法规则的判定结果,该数据集用于测试训练后模型所具备的固有语言倾向性。

The Stanford Sentiment Treebank (SST-2) [54], on the other hand, is a standard binary classification task.而斯坦福情感树库(SST-2)[54] 则是一项标准的二分类任务。

Our model obtains an score of 45.4 on CoLA, which is an especially big jump over the previous best result of 35.0, showcasing the innate linguistic bias learned by our model.我们的模型在 CoLA 数据集上取得了 45.4 分的成绩,相较于此前 35.0 的最优结果实现了大幅跃升,这体现出模型学习到了较强的固有语言倾向性。

The model also achieves 91.3% accuracy on SST-2, which is competitive with the state-of-the-art results.同时,模型在 SST-2 数据集上达到了 91.3% 的准确率,这一结果与当前领域内的最优水平具有竞争力。

We also achieve an overall score of 72.8 on the GLUE benchmark, which is significantly better than the previous best of 68.9.此外,我们的模型在 GLUE 基准测试集上取得了 72.8 的综合得分,显著优于此前 68.9 的最优综合得分。

(注:1. linguistic acceptability 译为语言可接受性,核心是判断句子在语法和语义上是否通顺合理;2. innate linguistic bias 译为固有语言倾向性,指模型从训练数据中习得的、对符合自然语言规则文本的偏好;3. binary classification task 译为二分类任务,此处 SST-2 的任务目标是判断文本情感为积极或消极。)

表4:语义相似度与文本分类任务实验结果

(本模型与当前最优方法的对比,表中所有任务均基于GLUE基准测试集完成评估。

标注说明:mc = 马修斯相关系数,acc = 准确率,pc = 皮尔逊相关系数)

术语与格式说明

- Mathews correlation(mc):译为马修斯相关系数,是衡量二分类模型性能的指标,尤其适用于样本不均衡的任务,取值范围为[-1,1],越接近1代表模型性能越好。

- Accuracy(acc):译为准确率,是分类任务的基础评估指标,计算方式为正确预测的样本数占总样本数的比例。

- Pearson correlation(pc):译为皮尔逊相关系数,用于衡量两个变量之间的线性相关程度,在语义相似度任务中常用来评估模型预测分数与人工标注分数的一致性,取值范围为[-1,1]。

- 表格标题保留学术论文的标准格式,括号内补充说明评估基准与指标缩写,符合学术排版规范。

5 Analysis

5 分析

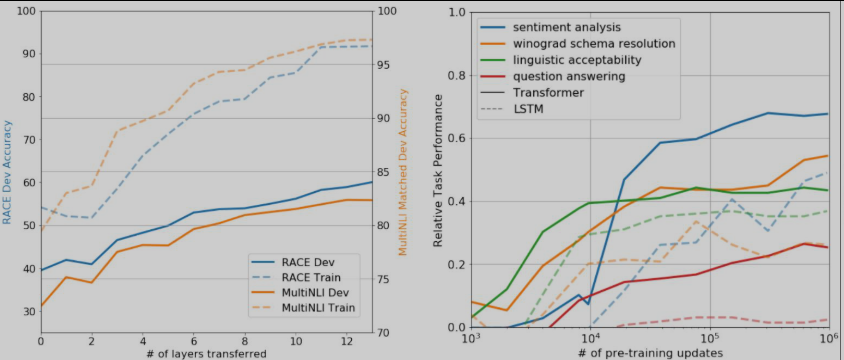

Impact of number of layers transferred We observed the impact of transferring a variable number of layers from unsupervised pre-training to the supervised target task.迁移层数的影响:我们探究了将无监督预训练阶段不同数量的网络层迁移至有监督目标任务时产生的效果。

Figure 2 (left) illustrates the performance of our approach on MultiNLI and RACE as a function of the number of layers transferred.图 2(左)展示了在 MultiNLI 与 RACE 任务上,模型性能随迁移层数变化的关系。

We observe the standard result that transferring embeddings improves performance and that each transformer layer provides further benefits up to 9% for full transfer on MultiNLI.实验得出了常规结论:迁移嵌入层能够提升模型性能;此外,每增加一个迁移的 Transformer 层,模型性能都会进一步优化,在 MultiNLI 任务上,当迁移全部网络层时,性能提升幅度最高可达 9%。

This indicates that each layer in the pre-trained model contains useful functionality for solving target tasks.这表明预训练模型中的每一层都蕴含着有助于解决目标任务的有效功能。

(注:1. transferring a variable number of layers 译为迁移不同数量的网络层,是迁移学习中常用的微调策略,用于探究预训练模型各层特征的有效性;2. as a function of 译为随…… 变化,是学术论文中描述变量间关系的常用表达;3. full transfer 译为迁移全部网络层,指将预训练模型的所有层参数全部迁移至目标任务中,而非仅迁移部分层。)

Figure 2: (left) Effect of transferring increasing number of layers from the pre-trained language model on RACE and MultiNLI. (right) Plot showing the evolution of zero-shot performance on different tasks as a function of LM pre-training updates. Performance per task is normalized between a random guess baseline and the current state-of-the-art with a single model.

图 2:(左)从预训练语言模型迁移递增数量的层对 RACE 和 MultiNLI 的影响。(右)曲线图显示了不同任务的零样本性能随 LM 预训练更新次数的演变。每个任务的性能都在随机猜测基线和当前使用单一模型的最佳水平之间进行了归一化。

Zero-shot Behaviors We’d like to better understand why language model pre-training of transformers is effective.零样本表现:我们希望进一步探究基于 Transformer 的语言模型预训练为何能取得良好效果。

A hypothesis is that the underlying generative model learns to perform many of the tasks we evaluate on in order to improve its language modeling capability and that the more structured attentional memory of the transformer assists in transfer compared to LSTMs.我们提出如下假设:一是底层生成式模型为提升自身的语言建模能力,会学习执行我们所评估的多项任务;二是与长短期记忆网络(LSTM)相比,Transformer 所具备的结构化更强的注意力记忆机制,更有助于迁移学习的开展。

We designed a series of heuristic solutions that use the underlying generative model to perform tasks without supervised finetuning.我们设计了一系列启发式方案,可借助底层生成式模型在无监督微调的条件下完成任务。

We visualize the effectiveness of these heuristic solutions over the course of generative pre-training in Fig 2 (right).图 2(右)可视化展示了这些启发式方案在生成式预训练过程中的有效性变化。

We observe the performance of these heuristics is stable and steadily increases over training suggesting that generative pretraining supports the learning of a wide variety of task relevant functionality.我们观察到,这些启发式方案的性能在训练过程中稳定且持续提升,这表明生成式预训练有助于模型学习到大量与任务相关的功能。

We also observe the LSTM exhibits higher variance in its zero-shot performance suggesting that the inductive bias of the Transformer architecture assists in transfer.同时我们发现,LSTM 模型的零样本性能波动更大,这说明 Transformer 架构的归纳偏置更有利于迁移学习。

(注:1. Zero-shot Behaviors 译为零样本表现,指模型在未经过目标任务监督训练的情况下,直接完成任务的能力;2. attentional memory 译为注意力记忆机制,是 Transformer 的核心组件,可捕捉文本中不同位置的语义关联;3. heuristic solutions 译为启发式方案,指基于经验或直观判断设计的非最优但实用的解决方案;4. inductive bias 译为归纳偏置,指模型架构自带的、用于从有限数据中归纳泛化规律的偏好假设。)

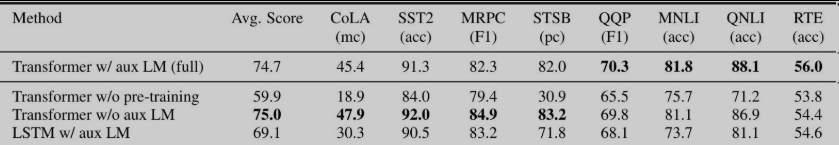

Table 5: Analysis of various model ablations on different tasks. Avg. score is a unweighted average of all the results. (mc= Mathews correlation, acc=Accuracy, pc=Pearson correlation)

表5:不同任务上各种模型消融的分析。平均分是所有结果的非加权平均值。(mc=马修斯相关系数,acc=准确率,pc=皮尔逊相关系数) Ablation studies We perform three different ablation studies (Table 5).

Ablation studies We perform three different ablation studies (Table 5).

消融实验:我们开展了三项不同的消融实验,实验结果如表5所示。

First, we examine the performance of our method without the auxiliary LM objective during fine-tuning. We observe that the auxiliary objective helps on the NLI tasks and QQP. Overall, the trend suggests that larger datasets benefit from the auxiliary objective but smaller datasets do not.

第一项实验:我们验证了微调阶段移除语言模型辅助目标后方法的性能表现。实验发现,该辅助目标对自然语言推理(NLI)任务和QQP任务均有性能增益。总体趋势表明,规模较大的数据集能从辅助目标中获益,而小规模数据集则无法获得显著提升。

Second, we analyze the effect of the Transformer by comparing it with a single layer 2048 unit LSTM using the same framework. We observe a 5.6 average score drop when using the LSTM instead of the Transformer. The LSTM only outperforms the Transformer on one dataset – MRPC.

第二项实验:我们在相同框架下,将Transformer模型与一个包含2048个单元的单层长短期记忆网络(LSTM)进行对比,以此分析Transformer架构的效果。结果显示,用LSTM替换Transformer后,模型平均得分下降5.6分;仅在MRPC这一个数据集上,LSTM的性能优于Transformer。

Finally, we also compare with our transformer architecture directly trained on supervised target tasks, without pre-training. We observe that the lack of pre-training hurts performance across all the tasks, resulting in a 14.8% decrease compared to our full model.

第三项实验:我们还将完整模型与未经过预训练、直接在有监督目标任务上训练的同结构Transformer模型进行了对比。实验发现,移除预训练步骤会损害模型在所有任务上的性能,与完整模型相比,性能下降幅度达14.8%。

(注:1. ablation studies 译为消融实验,是机器学习领域用于验证模型各组件有效性的常用实验方法,通过移除特定组件来观测性能变化;2. auxiliary LM objective 译为语言模型辅助目标,即前文提到的在微调阶段引入的语言建模任务,用于提升模型泛化能力;3. full model 译为完整模型,指包含预训练、辅助目标等全部设计的基准模型。)

6 Conclusion

6 结论

We introduced a framework for achieving strong natural language understanding with a single task-agnostic model through generative pre-training and discriminative fine-tuning.

我们提出了一套建模框架,该框架通过生成式预训练与判别式微调的组合策略,仅使用一个与任务无关的模型即可实现高性能的自然语言理解。

By pre-training on a diverse corpus with long stretches of contiguous text our model acquires significant world knowledge and ability to process long-range dependencies which are then successfully transferred to solving discriminative tasks such as question answering, semantic similarity assessment, entailment determination, and text classification, improving the state of the art on 9 of the 12 datasets we study.

模型在包含大段连续文本的多样化语料库上完成预训练后,能够习得丰富的世界知识与长距离依赖处理能力;这些能力可被成功迁移至各类判别式任务中,包括问答、语义相似度计算、蕴涵关系判定以及文本分类,最终在我们研究的12个数据集里,有9个数据集的性能突破了当时的最优水平。

Using unsupervised (pre-)training to boost performance on discriminative tasks has long been an important goal of Machine Learning research.

借助无监督(预)训练来提升判别式任务的性能,长期以来都是机器学习领域的重要研究目标。

Our work suggests that achieving significant performance gains is indeed possible, and offers hints as to what models (Transformers) and data sets (text with long range dependencies) work best with this approach.

本研究表明,通过该方法实现显著的性能提升是切实可行的,同时也指明了该方法适配度最高的模型类型(Transformer)与数据集类型(含长距离依赖的文本数据)。

We hope that this will help enable new research into unsupervised learning, for both natural language understanding and other domains, further improving our understanding of how and when unsupervised learning works.

我们希望本研究成果能够推动自然语言理解及其他领域中无监督学习的相关研究,进而加深学界对于无监督学习的适用场景与作用机制的理解。

(注:1. task-agnostic model 译为与任务无关的模型,指无需针对不同任务修改模型架构,仅通过微调即可适配各类任务;2. discriminative fine-tuning 译为判别式微调,特指针对分类、匹配等判别式任务设计的微调策略,区别于生成式任务的微调;3. world knowledge 译为世界知识,指模型从文本中习得的现实世界常识与事实信息,是提升语言理解能力的关键。)

References

参考文献

[1] S. Arora, Y. Liang, and T. Ma. A simple but tough-to-beat baseline for sentence embeddings. 2016.

[2] J. L. Ba, J. R. Kiros, and G. E. Hinton. Layer normalization. arXiv preprint arXiv:1607.06450, 2016.

[3] Y. Bengio, P. Lamblin, D. Popovici, and H. Larochelle. Greedy layer-wise training of deep networks. In Advances in neural information processing systems, pages 153–160, 2007.

[4] L. Bentivogli, P. Clark, I. Dagan, and D. Giampiccolo. The fifth pascal recognizing textual entailment challenge. In TAC, 2009.

[5] S. R. Bowman, G. Angeli, C. Potts, and C. D. Manning. A large annotated corpus for learning natural language inference. EMNLP, 2015.

[6] D. Cer, M. Diab, E. Agirre, I. Lopez-Gazpio, and L. Specia. Semeval-2017 task 1: Semantic textual similarity-multilingual and cross-lingual focused evaluation. arXiv preprint arXiv:1708.00055, 2017.

[7] S. Chaturvedi, H. Peng, and D. Roth. Story comprehension for predicting what happens next. In Proceedings of the 2017 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, pages 1603–1614, 2017.

[8] D. Chen and C. Manning. A fast and accurate dependency parser using neural networks. In Proceedings of the 2014 conference on empirical methods in natural language processing (EMNLP), pages 740–750, 2014.

[9] Z. Chen, H. Zhang, X. Zhang, and L. Zhao. Quora question pairs. https://data.quora.com/First-Quora Dataset-Release-Question-Pairs, 2018.

[10] R. Collobert and J. Weston. A unified architecture for natural language processing: Deep neural networks with multitask learning. In Proceedings of the 25th international conference on Machine learning, pages 160–167. ACM, 2008.

[11] R. Collobert, J. Weston, L. Bottou, M. Karlen, K. Kavukcuoglu, and P. Kuksa. Natural language processing (almost) from scratch. Journal of Machine Learning Research, 12(Aug):2493–2537, 2011.

[12] A. Conneau, D. Kiela, H. Schwenk, L. Barrault, and A. Bordes. Supervised learning of universal sentence representations from natural language inference data. EMNLP, 2017.

[13] A. M. Dai and Q. V. Le. Semi-supervised sequence learning. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, pages 3079–3087, 2015.

[14] W. B. Dolan and C. Brockett. Automatically constructing a corpus of sentential paraphrases. In Proceedings of the Third International Workshop on Paraphrasing (IWP2005), 2005.

[15] D. Erhan, Y. Bengio, A. Courville, P.-A. Manzagol, P. Vincent, and S. Bengio. Why does unsupervised pre-training help deep learning? Journal of Machine Learning Research, 11(Feb):625–660, 2010.

[16] S. Gray, A. Radford, and K. P. Diederik. Gpu kernels for block-sparse weights. 2017.

[17] Z. He, S. Liu, M. Li, M. Zhou, L. Zhang, and H. Wang. Learning entity representation for entity disambiguation. In Proceedings of the 51st Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 2: Short Papers), volume 2, pages 30–34, 2013.

[18] D. Hendrycks and K. Gimpel. Bridging nonlinearities and stochastic regularizers with gaussian error linear units. arXiv preprint arXiv:1606.08415, 2016.

[19] K. M. Hermann, T. Kocisky, E. Grefenstette, L. Espeholt, W. Kay, M. Suleyman, and P. Blunsom. Teaching machines to read and comprehend. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, pages 1693– 1701, 2015.

[20] G. E. Hinton, S. Osindero, and Y.-W. Teh. A fast learning algorithm for deep belief nets. Neural computation, 18(7):1527–1554, 2006.

[21] J. Howard and S. Ruder. Universal language model fine-tuning for text classification. Association for Computational Linguistics (ACL), 2018.

[22] Y. Jernite, S. R. Bowman, and D. Sontag. Discourse-based objectives for fast unsupervised sentence representation learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:1705.00557, 2017.

[23] Y. Ji and J. Eisenstein. Discriminative improvements to distributional sentence similarity. In Proceedings of the 2013 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, pages 891–896, 2013.

[24] F. Jiao, S. Wang, C.-H. Lee, R. Greiner, and D. Schuurmans. Semi-supervised conditional random fields for improved sequence segmentation and labeling. In Proceedings of the 21st International Conference on Computational Linguistics and the 44th annual meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, pages 209–216. Association for Computational Linguistics, 2006.

[25] T. Khot, A. Sabharwal, and P. Clark. Scitail: A textual entailment dataset from science question answering. In Proceedings of AAAI, 2018.

[26] Y. Kim. Convolutional neural networks for sentence classification. EMNLP, 2014.

[27] D. P. Kingma and J. Ba. Adam: A method for stochastic optimization. arXiv preprint arXiv:1412.6980, 2014.

[28] R. Kiros, Y. Zhu, R. R. Salakhutdinov, R. Zemel, R. Urtasun, A. Torralba, and S. Fidler. Skip-thought vectors. In Advances in neural information processing systems, pages 3294–3302, 2015.

[29] N. Kitaev and D. Klein. Constituency parsing with a self-attentive encoder. ACL, 2018.

[30] G. Lai, Q. Xie, H. Liu, Y. Yang, and E. Hovy. Race: Large-scale reading comprehension dataset from examinations. EMNLP, 2017.

[31] G. Lample, L. Denoyer, and M. Ranzato. Unsupervised machine translation using monolingual corpora only. ICLR, 2018.

[32] Q. Le and T. Mikolov. Distributed representations of sentences and documents. In International Conference on Machine Learning, pages 1188–1196, 2014.

[33] P. Liang. Semi-supervised learning for natural language. PhD thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2005.

[34] P. J. Liu, M. Saleh, E. Pot, B. Goodrich, R. Sepassi, L. Kaiser, and N. Shazeer. Generating wikipedia by summarizing long sequences. ICLR, 2018.

[35] X. Liu, K. Duh, and J. Gao. Stochastic answer networks for natural language inference. arXiv preprint arXiv:1804.07888, 2018.

[36] L. Logeswaran and H. Lee. An efficient framework for learning sentence representations. ICLR, 2018.

[37] I. Loshchilov and F. Hutter. Fixing weight decay regularization in adam. arXiv preprint arXiv:1711.05101, 2017.

[38] B. McCann, J. Bradbury, C. Xiong, and R. Socher. Learned in translation: Contextualized word vectors. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, pages 6297–6308, 2017.

[39] T. Mikolov, I. Sutskever, K. Chen, G. S. Corrado, and J. Dean. Distributed representations of words and phrases and their compositionality. In Advances in neural information processing systems, pages 3111–3119, 2013.

[40] N. Mostafazadeh, M. Roth, A. Louis, N. Chambers, and J. Allen. Lsdsem 2017 shared task: The story cloze test. In Proceedings of the 2nd Workshop on Linking Models of Lexical, Sentential and Discourse-level Semantics, pages 46–51, 2017.

[41] K. Nigam, A. McCallum, and T. Mitchell. Semi-supervised text classification using em. Semi-Supervised Learning, pages 33–56, 2006.

[42] J. Pennington, R. Socher, and C. Manning. Glove: Global vectors for word representation. In Proceedings of the 2014 conference on empirical methods in natural language processing (EMNLP), pages 1532–1543, 2014.

[43] M. E. Peters, W. Ammar, C. Bhagavatula, and R. Power. Semi-supervised sequence tagging with bidirectional language models. ACL, 2017.

[44] M. E. Peters, M. Neumann, M. Iyyer, M. Gardner, C. Clark, K. Lee, and L. Zettlemoyer. Deep contextualized word representations. NAACL, 2018.

[45] Y. Qi, D. S. Sachan, M. Felix, S. J. Padmanabhan, and G. Neubig. When and why are pre-trained word embeddings useful for neural machine translation? NAACL, 2018.

[46] A. Rahman and V. Ng. Resolving complex cases of definite pronouns: the winograd schema challenge. In Proceedings of the 2012 Joint Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing and Computational Natural Language Learning, pages 777–789. Association for Computational Linguistics, 2012.

[47] P. Rajpurkar, J. Zhang, K. Lopyrev, and P. Liang. Squad: 100,000+ questions for machine comprehension of text. EMNLP, 2016.

[48] P. Ramachandran, P. J. Liu, and Q. V. Le. Unsupervised pretraining for sequence to sequence learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:1611.02683, 2016.

[49] M. Ranzato, C. Poultney, S. Chopra, and Y. LeCun. Efficient learning of sparse representations with an energy-based model. In Advances in neural information processing systems, pages 1137–1144, 2007.

[50] M. Rei. Semi-supervised multitask learning for sequence labeling. ACL, 2017.

[51] H. Robbins and S. Monro. A stochastic approximation method. The annals of mathematical statistics, pages 400–407, 1951.

[52] T. Rocktäschel, E. Grefenstette, K. M. Hermann, T. Kociskˇ y,` and P. Blunsom. Reasoning about entailment with neural attention. arXiv preprint arXiv:1509.06664, 2015.

[53] R. Sennrich, B. Haddow, and A. Birch. Neural machine translation of rare words with subword units. arXiv preprint arXiv:1508.07909, 2015.

[54] R. Socher, A. Perelygin, J. Wu, J. Chuang, C. D. Manning, A. Ng, and C. Potts. Recursive deep models for semantic compositionality over a sentiment treebank. In Proceedings of the 2013 conference on empirical methods in natural language processing, pages 1631–1642, 2013.

[55] S. Srinivasan, R. Arora, and M. Riedl. A simple and effective approach to the story cloze test. arXiv preprint arXiv:1803.05547, 2018.

[56] S. Subramanian, A. Trischler, Y. Bengio, and C. J. Pal. Learning general purpose distributed sentence representations via large scale multi-task learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:1804.00079, 2018.

[57] J. Suzuki and H. Isozaki. Semi-supervised sequential labeling and segmentation using giga-word scale unlabeled data. Proceedings of ACL-08: HLT, pages 665–673, 2008.

[58] Y. Tay, L. A. Tuan, and S. C. Hui. A compare-propagate architecture with alignment factorization for natural language inference. arXiv preprint arXiv:1801.00102, 2017.

[59] Y. Tay, L. A. Tuan, and S. C. Hui. Multi-range reasoning for machine comprehension. arXiv preprint arXiv:1803.09074, 2018.

[60] J. Tian, Z. Zhou, M. Lan, and Y. Wu. Ecnu at semeval-2017 task 1: Leverage kernel-based traditional nlp features and neural networks to build a universal model for multilingual and cross-lingual semantic textual similarity. In Proceedings of the 11th International Workshop on Semantic Evaluation (SemEval-2017), pages 191–197, 2017.

[61] Y. Tsvetkov. Opportunities and challenges in working with low-resource languages. CMU, 2017.

[62] A. Vaswani, N. Shazeer, N. Parmar, J. Uszkoreit, L. Jones, A. N. Gomez, Ł. Kaiser, and I. Polosukhin. Attention is all you need. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, pages 6000–6010, 2017.

[63] P. Vincent, H. Larochelle, Y. Bengio, and P.-A. Manzagol. Extracting and composing robust features with denoising autoencoders. In Proceedings of the 25th international conference on Machine learning, pages 1096–1103. ACM, 2008.

[64] A. Wang, A. Singh, J. Michael, F. Hill, O. Levy, and S. R. Bowman. Glue: A multi-task benchmark and analysis platform for natural language understanding. arXiv preprint arXiv:1804.07461, 2018.

[65] A. Warstadt, A. Singh, and S. R. Bowman. Corpus of linguistic acceptability. http://nyu-mll.github.io/cola, 2018.

[66] A. Williams, N. Nangia, and S. R. Bowman. A broad-coverage challenge corpus for sentence understanding through inference. NAACL, 2018.

[67] Y. Xu, J. Liu, J. Gao, Y. Shen, and X. Liu. Towards human-level machine reading comprehension: Reasoning and inference with multiple strategies. arXiv preprint arXiv:1711.04964, 2017.

[68] D. Yu, L. Deng, and G. Dahl. Roles of pre-training and fine-tuning in context-dependent dbn-hmms for real-world speech recognition. In Proc. NIPS Workshop on Deep Learning and Unsupervised Feature Learning, 2010.

[69] R. Zhang, P. Isola, and A. A. Efros. Split-brain autoencoders: Unsupervised learning by cross-channel prediction. In CVPR, volume 1, page 6, 2017.

[70] X. Zhu. Semi-supervised learning literature survey. 2005.

[71] Y. Zhu, R. Kiros, R. Zemel, R. Salakhutdinov, R. Urtasun, A. Torralba, and S. Fidler. Aligning books and movies: Towards story-like visual explanations by watching movies and reading books. In Proceedings of the IEEE international conference on computer vision, pages 19–27, 2015.

更多推荐

已为社区贡献77条内容

已为社区贡献77条内容

所有评论(0)