【LLM Agent 理论基础】读复旦米哈游综述3 原文background部分

🧩 2 Background — 背景

English

In this section, we provide crucial background information to lay the groundwork for the subsequent content (§ 2.1). We first discuss the origin of AI agents, from philosophy to AI, coupled with the debate on the existence of artificial agents (§ 2.2). Then we summarize the technological evolution of AI agents. Finally, we explain the key characteristics of agents and why LLMs are suitable as the “brain” (§ 2.3).

中文

本节旨在为后续内容奠定理论基础。

我们首先从哲学到人工智能领域讨论AI 智能体的起源及人工智能体能否具备“能动性”的争论(§ 2.1)。

随后从技术趋势角度总结智能体的发展历程(§ 2.2)。

最后介绍智能体的关键特征,并说明为何LLM适合作为其“大脑”(§ 2.3)。

2.1 Origin of AI Agent — 智能体的起源

1️⃣ Agent in Philosophy — 哲学视角的“智能体”

English

The concept of an agent has deep philosophical roots, traceable to Aristotle and Hume [5].

Broadly, an agent is any entity capable of acting; agency means exercising that capacity [5].

Narrowly, agency concerns intentional action — entities with desires, beliefs, intentions, and the ability to act [32–35].

Agents may include humans, animals, or abstract entities, physical or virtual.

Crucially, agency implies autonomy: acting by volition, not mere reaction.

中文

“智能体(agent)”概念起源于哲学,可追溯至亚里士多德与休谟 [5]。

广义上,智能体是任何具有行动能力的实体;“能动性(agency)”即行使该能力 [5]。

狭义上,它指有意图的行动者,具备“欲望—信念—意图”等心理状态 [32–35]。

智能体可包括人、动物,甚至抽象或虚拟实体。

其核心特征是自主性——基于意志行动,而非被动反应。

💡 关键词:Agency = 行动能力;Autonomy = 自主性

🔍 注释:哲学层面的智能体强调内在意图与自我决定,这成为后续AI定义的思想源。

2️⃣ Can Artificial Entities Have Agency? — 人工系统能否具备能动性?

English

If agency simply means “capacity to act,” AI systems already show agency [5].

But in philosophy, agency usually implies consciousness and intentionality [32–34]; hence it’s unclear whether machines possess internal states like desire or belief.

Critics view attributing such states to machines as anthropomorphism [36].

Others argue that using an intentional stance — interpreting actions as intentional — helps explain AI behavior [11, 37, 38].

中文

若仅将能动性理解为“行动能力”,AI 系统已具备某种能动性 [5]。

但在哲学意义上,它还包含意识与意向性 [32–34],因此人工系统是否真正拥有“欲望或信念”仍存争议。

批评者认为这种类比是拟人化(anthropomorphism) [36];

而另一派则主张采用**意向立场(intentional stance)**解释人工体的行为,有助于描述其决策与抽象模式 [11, 37, 38]。

💡 关键词:Intentional stance 意向立场;Anthropomorphism 拟人化

🔍 注释:这场争论对应LLM“是否真正理解语言”的哲学根基。

3️⃣ Language Models and Artificial Intentional Agents — 语言模型与“人工意向体”

English

Language models are conditional-probability machines predicting the next token [42]; humans, in contrast, speak from mental states [43, 44].

Some thus say LMs lack genuine intentionality [30, 45].

Others propose that LMs can approximate belief–desire–intention representations during next-word prediction [46, 47]; experiments show partial evidence [46, 48, 49].

中文

语言模型本质上是条件概率模型,依据输入预测下一个词 [42];

而人类语言产生依赖心理与感知状态 [43, 44]。

因此部分学者认为语言模型不具备真正的意向性 [30, 45]。

另一些研究者则认为,语言模型在预测过程中可隐式推测上下文中隐含的信念、欲望与意图 [46, 47],并已得到实验支持 [46, 48, 49]。

💬 这为LLM“能否被视为智能体”提供了经验层面的佐证。

4️⃣ Introduction of Agents into AI — 从哲学到人工智能

English

Before the mid-1980s, “agent” was rare in mainstream AI.

Interest surged later [50–53].

Wooldridge et al. [4] define AI as building computer-based agents exhibiting intelligent behavior.

In philosophy, agents could be humans or animals; in AI, they are computational entities [4, 7].

Because inner states like consciousness are unverifiable [11], researchers focus on observable traits — autonomy, reactivity, pro-activeness, social ability [4, 9].

Some hold that intelligence is “in the eye of the beholder” [54, 55].

Thus, an AI agent concretizes the philosophical idea in computational form: it perceives via sensors, decides, and acts via actuators [1, 4].

中文

在20世纪80年代中期之前,“智能体”概念在主流AI研究中鲜被提及。

此后该主题迅速升温 [50–53]。

Wooldridge 等 [4] 指出:AI 可定义为构建展示智能行为的计算型智能体。

哲学中的智能体可为人或动物;AI 中的智能体则是计算实体 [4, 7]。

由于“意识”“欲望”等内在状态难以验证 [11],研究者转而关注可观察属性:自主性、反应性、主动性、社会性 [4, 9]。

有人认为“智能存在于观察者的眼中” [54, 55]。

因此,AI 智能体是哲学“能动者”在计算语境下的具象化:感知—决策—行动 闭环 [1, 4]。

2.2 Technological Trends in Agent Research — 技术演进

1️⃣ Symbolic Agents — 符号智能体

基于符号逻辑 [56, 57];知识以符号表示并推理 [58]。

优势:可解释、表达力强 [13, 14, 60]。

局限:难处理不确定性与大规模现实问题,推理效率低 [19–21, 61]。

💡 代表:专家系统 (Expert Systems)。

2️⃣ Reactive Agents — 反应式智能体

无复杂推理,强调感知–行动闭环 [15, 16, 20, 62]。

快速响应、资源占用低 [52];

但缺乏高层规划与长期目标 [63]。

💡 典型:行为式机器人 (Behavior-based Robots)。

3️⃣ Reinforcement-Learning Agents — 强化学习智能体

通过与环境交互获得累积奖励最大化 [17, 18, 64]。

早期:Q-learning [66]、SARSA [67];

深度阶段:Deep RL (AlphaGo [70], DQN [71])。

优势:自主学习、无需人工标签;

问题:训练时间长、样本效率低、稳定性差 [21]。

4️⃣ Agents with Transfer & Meta Learning — 迁移与元学习智能体

Transfer Learning 提升跨任务迁移 [77–79];

Meta Learning 实现“学习如何学习” [80–85]。

挑战:任务差异导致负迁移 [86, 87];

元学习需大量预训练样本 [81, 88]。

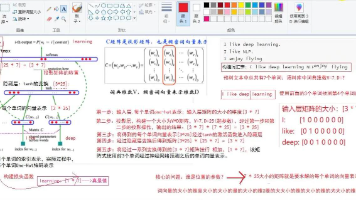

5️⃣ LLM-Based Agents — 基于大型语言模型的智能体

LLMs 展现涌现能力 [24–26, 41],研究者以其为“脑” [22, 27–28, 89],

并通过多模态感知与工具调用扩展感知/行动空间 [90–94]。

LLM 智能体既能像符号智能体那样进行CoT 推理与规划 [95–101],

又能像反应式智能体那样基于反馈学习并执行行动 [102–104]。

凭借预训练语料与少样本泛化,它们能实现任务迁移 [105–107]。

应用领域:软件开发、科学研究 [108–110];

多智能体交互可产生协作与竞争行为,甚至出现社会现象 [22, 108–112]。

💡 关键词:CoT (Chain of Thought);Tool Use;Emergent Sociality

🔍 注释:这一步奠定了“LLM = 脑,工具 = 行动,环境 = 感知”的现代框架。

2.3 Why LLM as Agent Brain — 为何LLM可作“大脑”

| 属性 | 定义 | LLM 体现 |

|---|---|---|

| Autonomy 自主性 | 无需人工干预,自主决策 [4, 113] | 可独立生成文本、规划任务 (Auto-GPT 等 [114]) |

| Reactivity 反应性 | 对环境变化快速响应 [9] | 通过多模态输入、具身化与工具调用实现感知-行动 [25, 92, 120] |

| Pro-activeness 主动性 | 主动制定目标与计划 [9] | 通过 CoT 与任务分解展现推理与规划 [95–100] |

| Social Ability 社会性 | 能与人或智能体交流 [8] | 自然语言交互、角色扮演、协作与竞争 [108–130] |

💬 挑战:LLM 的“思考再行动”导致响应延迟,但符合“先思考再行动”的人类模式 [122, 123]。

📎 MoA4NAD 启示:在设计多Agent协作时,可让LLM承担决策核心,外围以工具与感知层补足反应与执行。

✅ Section 2 Key Takeaways — 要点总结

| 模块 | 核心思想 | 对 MoA4NAD 启示 |

|---|---|---|

| 哲学起源 | 智能体 = 有意图的行动者 | 决策层可借鉴 BDI 模型 |

| 计算转化 | Agent → 可观测属性:自治、反应、主动、社交 | 可量化智能体表现 |

| 技术演进 | Symbolic → Reactive → RL → Transfer/Meta → LLM | 为 Agent Pipeline 提供时间序列框架 |

| LLM 优势 | 自然语言理解、规划、社会互动 | 作为 Brain 模块核心;感知与行动通过 Function Call 扩展 |

更多推荐

已为社区贡献4条内容

已为社区贡献4条内容

所有评论(0)