【转】Rust语言圣经之定海神针 Pin 和 Unpin

说明:下面文章中有个人的补充说明内容。谨供参考。

定海神针 Pin 和 Unpin

在 Rust 异步编程中,有一个定海神针般的存在,它就是 Pin,作用说简单也简单,说复杂也非常复杂,当初刚出来时就连一些 Rust 大佬都一头雾水,何况瑟瑟发抖的我。好在今非昔比,目前网上的资料已经很全,而我就借花献佛,给大家好好讲讲这个 Pin。

在 Rust 中,所有的类型可以分为两类:

- 类型的值可以在内存中安全地被移动,例如数值、字符串、布尔值、结构体、枚举,总之你能想到的几乎所有类型都可以落入到此范畴内

- 自引用类型,大魔王来了,大家快跑,在之前章节我们已经见识过它的厉害

下面就是一个自引用类型

struct SelfRef {

value: String,

pointer_to_value: *mut String,

}

在上面的结构体中,pointer_to_value 是一个裸指针,指向第一个字段 value 持有的字符串 String 。很简单对吧?现在考虑一个情况, 若 value 被移动了怎么办?

此时一个致命的问题就出现了:value 的内存地址变了,而 pointer_to_value 依然指向 value 之前的地址,一个重大 bug 就出现了!

灾难发生,英雄在哪?只见 Pin 闪亮登场,它可以防止一个类型在内存中被移动。再来回忆下之前在 Future 章节中,我们提到过在 poll 方法的签名中有一个 self: Pin<&mut Self> ,那么为何要在这里使用 Pin 呢?

为何需要 Pin

其实 Pin 还有一个小伙伴 UnPin ,与前者相反,后者表示类型可以在内存中安全地移动。在深入之前,我们先来回忆下 async/.await 是如何工作的:

let fut_one = /* ... */; // Future 1

let fut_two = /* ... */; // Future 2

async move {

fut_one.await;

fut_two.await;

}

在底层,async 会创建一个实现了 Future 的匿名类型,并提供了一个 poll 方法:

// `async { ... }`语句块创建的 `Future` 类型

struct AsyncFuture {

fut_one: FutOne,

fut_two: FutTwo,

state: State,

}

// `async` 语句块可能处于的状态

enum State {

AwaitingFutOne,

AwaitingFutTwo,

Done,

}

impl Future for AsyncFuture {

type Output = ();

fn poll(mut self: Pin<&mut Self>, cx: &mut Context<'_>) -> Poll<()> {

loop {

match self.state {

State::AwaitingFutOne => match self.fut_one.poll(..) {

Poll::Ready(()) => self.state = State::AwaitingFutTwo,

Poll::Pending => return Poll::Pending,

}

State::AwaitingFutTwo => match self.fut_two.poll(..) {

Poll::Ready(()) => self.state = State::Done,

Poll::Pending => return Poll::Pending,

}

State::Done => return Poll::Ready(()),

}

}

}

}

当 poll 第一次被调用时,它会去查询 fut_one 的状态,若 fut_one 无法完成,则 poll 方法会返回。未来对 poll 的调用将从上一次调用结束的地方开始。该过程会一直持续,直到 Future 完成为止。

然而,如果我们的 async 语句块中使用了引用类型,会发生什么?例如下面例子:

async {

let mut x = [0; 128];

let read_into_buf_fut = read_into_buf(&mut x);

read_into_buf_fut.await;

println!("{:?}", x);

}

这段代码会编译成下面的形式:

struct ReadIntoBuf<'a> {

buf: &'a mut [u8], // 指向下面的`x`字段

}

struct AsyncFuture {

x: [u8; 128],

read_into_buf_fut: ReadIntoBuf<'what_lifetime?>,

}

这里,ReadIntoBuf 拥有一个引用字段,指向了结构体的另一个字段 x ,一旦 AsyncFuture 被移动,那 x 的地址也将随之变化,此时对 x 的引用就变成了不合法的,也就是 read_into_buf_fut.buf 会变为不合法的。

总结:当async fn或async block中有参数的生命周期时,此时生命周期也会存储到future当中,这就形成了一个自引用(self-referential)类型。所以需要用Pin。【此处为笔者补充!】

若能将 Future 在内存中固定到一个位置,就可以避免这种问题的发生,也就可以安全的创建上面这种引用类型。

【进一步补充】

对于下面的代码:

use tokio::io::{self, AsyncReadExt};

use tokio::fs::File;

#[tokio::main]

async fn main() -> io::Result<()> {

let mut f = File::open("foo.txt").await?;

let mut buffer = Vec::new();

// 读取整个文件的内容

f.read_to_end(&mut buffer).await?;

Ok(())

}

可以在playgroud中,查看对应的MIR和HIR代码:

//部分MIR代码

fn main::{closure#0}(_1: Pin<&mut {async block@src/main.rs:4:1: 4:15}>, _2: &mut Context<'_>) -> Poll<Result<(), std::io::Error>> {

debug _task_context => _31;

let mut _0: std::task::Poll<std::result::Result<(), std::io::Error>>;

let mut _3: std::ops::ControlFlow<std::result::Result<std::convert::Infallible, std::io::Error>, tokio::fs::File>;

let mut _4: {async fn body of tokio::fs::File::open<&str>()};

let mut _5: {async fn body of tokio::fs::File::open<&str>()};

let mut _6: std::task::Poll<std::result::Result<tokio::fs::File, std::io::Error>>;

let mut _7: std::pin::Pin<&mut {async fn body of tokio::fs::File::open<&str>()}>;

let mut _8: &mut {async fn body of tokio::fs::File::open<&str>()};

let mut _9: &mut std::task::Context<'_>;

let mut _10: isize;

let mut _12: isize;

let _13: std::result::Result<std::convert::Infallible, std::io::Error>;

let _14: tokio::fs::File;

let mut _15: std::ops::ControlFlow<std::result::Result<std::convert::Infallible, std::io::Error>, usize>;

let mut _16: tokio::io::util::read_to_end::ReadToEnd<'_, tokio::fs::File>;

let mut _17: tokio::io::util::read_to_end::ReadToEnd<'_, tokio::fs::File>;

let mut _18: &mut tokio::fs::File;

let mut _19: &mut std::vec::Vec<u8>;

let mut _20: std::task::Poll<std::result::Result<usize, std::io::Error>>;

let mut _21: std::pin::Pin<&mut tokio::io::util::read_to_end::ReadToEnd<'_, tokio::fs::File>>;

let mut _22: &mut tokio::io::util::read_to_end::ReadToEnd<'_, tokio::fs::File>;

....

}

上面的信息可供参考。

Unpin

事实上,绝大多数类型都不在意是否被移动(开篇提到的第一种类型),因此它们都自动实现了 Unpin 特征。

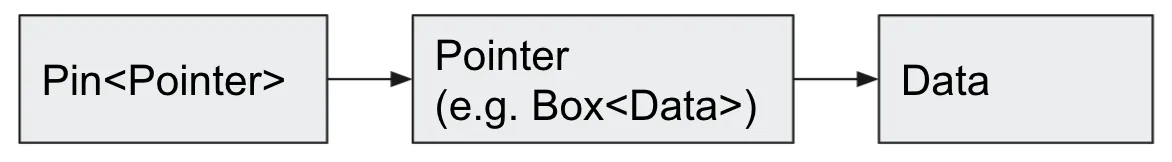

从名字推测,大家可能以为 Pin 和 Unpin 都是特征吧?实际上,Pin 不按套路出牌,它是一个结构体:

pub struct Pin<P> {

pointer: P,

}

它包裹一个指针,并且能确保该指针指向的数据不会被移动,例如 Pin<&mut T> , Pin<&T> , Pin<Box> ,都能确保 T 不会被移动。

而 Unpin 才是一个特征,它表明一个类型可以随意被移动,那么问题来了,可以被 Pin 住的值,它有没有实现什么特征呢? 答案很出乎意料,可以被 Pin 住的值实现的特征是 !Unpin ,大家可能之前没有见过,但是它其实很简单,! 代表没有实现某个特征的意思,!Unpin 说明类型没有实现 Unpin 特征,那自然就可以被 Pin 了。

那是不是意味着类型如果实现了 Unpin 特征,就不能被 Pin 了?其实,还是可以 Pin 的,毕竟它只是一个结构体,你可以随意使用,但是不再有任何效果而已,该值一样可以被移动!

例如 Pin<&mut u8> ,显然 u8 实现了 Unpin 特征,它可以在内存中被移动,因此 Pin<&mut u8> 跟 &mut u8 实际上并无区别,一样可以被移动。

因此,一个类型如果不能被移动,它必须实现 !Unpin 特征。如果大家对 Pin 、 Unpin 还是模模糊糊,建议再重复看一遍之前的内容,理解它们对于我们后面要讲到的内容非常重要!

如果将 Unpin 与之前章节学过的 Send/Sync 进行下对比,会发现它们都很像:

都是标记特征( marker trait ),该特征未定义任何行为,非常适用于标记

都可以通过!语法去除实现

绝大多数情况都是自动实现, 无需我们的操心

深入理解 Pin

对于上面的问题,我们可以简单的归结为如何在 Rust 中处理自引用类型(果然,只要是难点,都和自引用脱离不了关系),下面用一个稍微简单点的例子来理解下 Pin :

#[derive(Debug)]

struct Test {

a: String,

b: *const String,

}

impl Test {

fn new(txt: &str) -> Self {

Test {

a: String::from(txt),

b: std::ptr::null(),

}

}

fn init(&mut self) {

let self_ref: *const String = &self.a;

self.b = self_ref;

}

fn a(&self) -> &str {

&self.a

}

fn b(&self) -> &String {

assert!(!self.b.is_null(), "Test::b called without Test::init being called first");

unsafe { &*(self.b) }

}

}

Test 提供了方法用于获取字段 a 和 b 的值的引用。这里b 是 a 的一个引用,但是我们并没有使用引用类型而是用了裸指针,原因是:Rust 的借用规则不允许我们这样用,因为不符合生命周期的要求。 此时的 Test 就是一个自引用结构体。

如果不移动任何值,那么上面的例子将没有任何问题,例如:

fn main() {

let mut test1 = Test::new("test1");

test1.init();

let mut test2 = Test::new("test2");

test2.init();

println!("a: {}, b: {}", test1.a(), test1.b());

println!("a: {}, b: {}", test2.a(), test2.b());

}

输出非常正常:

a: test1, b: test1

a: test2, b: test2

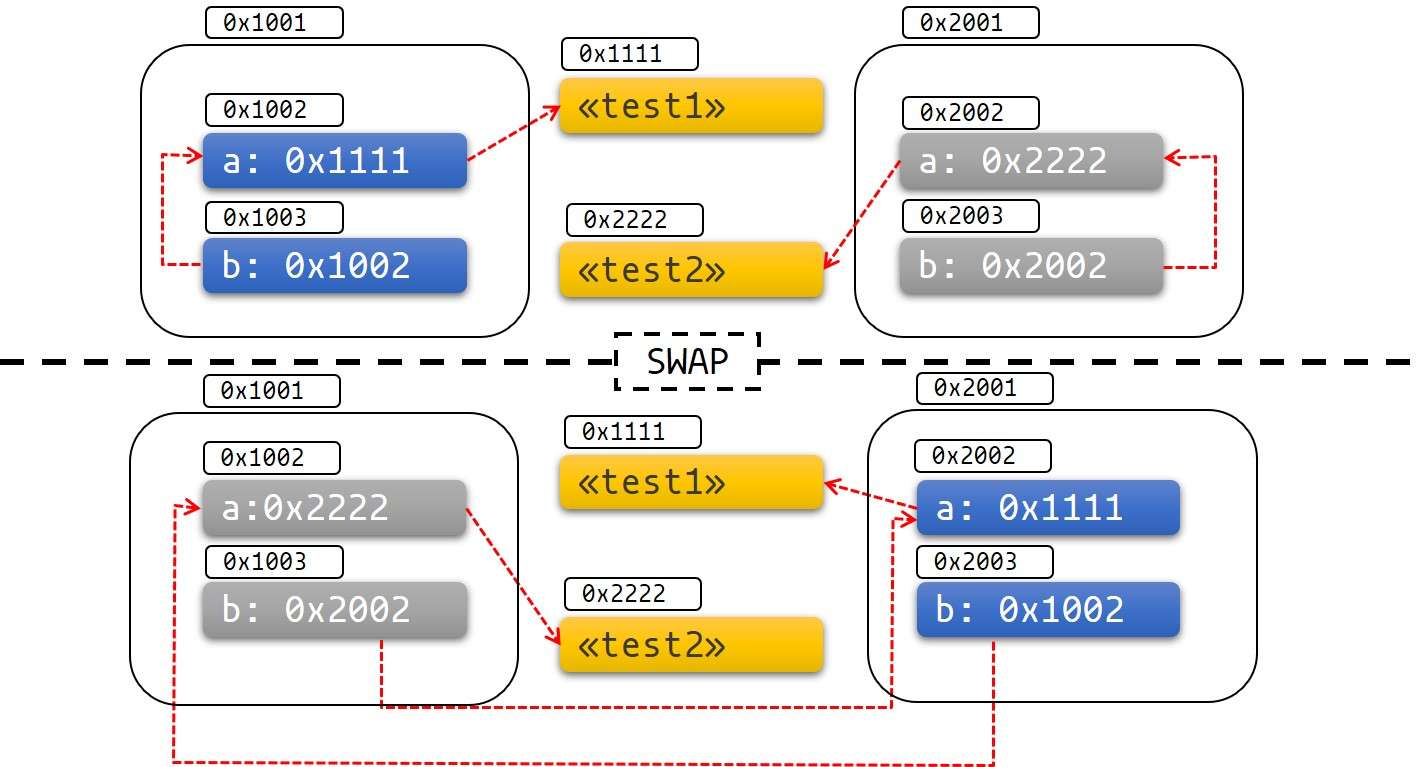

明知山有虎,偏向虎山行,这才是我辈年轻人的风华。既然移动数据会导致指针不合法,那我们就移动下数据试试,将 test1 和 test2 进行下交换:

fn main() {

let mut test1 = Test::new("test1");

test1.init();

let mut test2 = Test::new("test2");

test2.init();

println!("a: {}, b: {}", test1.a(), test1.b());

std::mem::swap(&mut test1, &mut test2);

println!("a: {}, b: {}", test2.a(), test2.b());

}

按理来说,这样修改后,输出应该如下:

a: test1, b: test1

a: test1, b: test1

但是实际运行后,却产生了下面的输出:

a: test1, b: test1

a: test1, b: test2

原因是 test2.b 指针依然指向了旧的地址,而该地址对应的值现在在 test1 里,最终会打印出意料之外的值。

如果大家还是将信将疑,那再看看下面的代码:

fn main() {

let mut test1 = Test::new("test1");

test1.init();

let mut test2 = Test::new("test2");

test2.init();

println!("a: {}, b: {}", test1.a(), test1.b());

std::mem::swap(&mut test1, &mut test2);

test1.a = "I've totally changed now!".to_string();

println!("a: {}, b: {}", test2.a(), test2.b());

}

下面的图片也可以帮助更好的理解这个过程:

Pin 在实践中的运用

在理解了 Pin 的作用后,我们再来看看它怎么帮我们解决问题。

将值固定到栈上,PhantomPinned出场

【源码补充:PhantomPinned实现了!Unpin】

// https://doc.rust-lang.org/src/core/marker.rs.html#1005

#[stable(feature = "pin", since = "1.33.0")]

#[derive(Debug, Default, Copy, Clone, Eq, PartialEq, Ord, PartialOrd, Hash)]

pub struct PhantomPinned;

#[stable(feature = "pin", since = "1.33.0")]

impl !Unpin for PhantomPinned {}

回到之前的例子,我们可以用 Pin 来解决指针指向的数据被移动的问题:

use std::pin::Pin;

use std::marker::PhantomPinned;

#[derive(Debug)]

struct Test {

a: String,

b: *const String,

_marker: PhantomPinned,

}

impl Test {

fn new(txt: &str) -> Self {

Test {

a: String::from(txt),

b: std::ptr::null(),

_marker: PhantomPinned, // 这个标记可以让我们的类型自动实现特征`!Unpin`

}

}

fn init(self: Pin<&mut Self>) {

let self_ptr: *const String = &self.a;

let this = unsafe { self.get_unchecked_mut() };

this.b = self_ptr;

}

fn a(self: Pin<&Self>) -> &str {

&self.get_ref().a

}

fn b(self: Pin<&Self>) -> &String {

assert!(!self.b.is_null(), "Test::b called without Test::init being called first");

unsafe { &*(self.b) }

}

}

上面代码中,我们使用了一个标记类型 PhantomPinned 将自定义结构体 Test 变成了 !Unpin (编译器会自动帮我们实现),因此该结构体无法再被移动。

一旦类型实现了 !Unpin ,那将它的值固定到栈( stack )上就是不安全的行为,因此在代码中我们使用了 unsafe 语句块来进行处理,你也可以使用 pin_utils 来避免 unsafe 的使用。

BTW, Rust 中的 unsafe 其实没有那么可怕,虽然听上去很不安全,但是实际上 Rust 依然提供了很多机制来帮我们提升了安全性,因此不必像对待 Go 语言的 unsafe 那样去畏惧于使用 Rust 中的 unsafe ,大致使用原则总结如下:没必要用时,就不要用,当有必要用时,就大胆用,但是尽量控制好边界,让 unsafe 的范围尽可能小。

此时,再去尝试移动被固定的值,就会导致编译错误:

pub fn main() {

// 此时的`test1`可以被安全的移动

let mut test1 = Test::new("test1");

// 新的`test1`由于使用了`Pin`,因此无法再被移动,这里的声明会将之前的`test1`遮蔽掉(shadow)

let mut test1 = unsafe { Pin::new_unchecked(&mut test1) };

Test::init(test1.as_mut());

let mut test2 = Test::new("test2");

let mut test2 = unsafe { Pin::new_unchecked(&mut test2) };

Test::init(test2.as_mut());

println!("a: {}, b: {}", Test::a(test1.as_ref()), Test::b(test1.as_ref()));

std::mem::swap(test1.get_mut(), test2.get_mut());

println!("a: {}, b: {}", Test::a(test2.as_ref()), Test::b(test2.as_ref()));

}

注意到之前的粗体字了吗?是的,Rust 并不是在运行时做这件事,而是在编译期就完成了,因此没有额外的性能开销!来看看报错:

error[E0277]: `PhantomPinned` cannot be unpinned

--> src/main.rs:47:43

|

47 | std::mem::swap(test1.get_mut(), test2.get_mut());

| ^^^^^^^ within `Test`, the trait `Unpin` is not implemented for `PhantomPinned`

需要注意的是固定在栈上非常依赖于你写出的 unsafe 代码的正确性。我们知道 &'a mut T 可以固定的生命周期是 'a ,但是我们却不知道当生命周期 'a 结束后,该指针指向的数据是否会被移走。如果你的 unsafe 代码里这么实现了,那么就会违背 Pin 应该具有的作用!

一个常见的错误就是忘记去遮蔽( shadow )初始的变量,因为你可以 drop 掉 Pin ,然后在 &'a mut T 结束后去移动数据:

fn main() {

let mut test1 = Test::new("test1");

let mut test1_pin = unsafe { Pin::new_unchecked(&mut test1) };

Test::init(test1_pin.as_mut());

drop(test1_pin);

println!(r#"test1.b points to "test1": {:?}..."#, test1.b);

let mut test2 = Test::new("test2");

mem::swap(&mut test1, &mut test2);

println!("... and now it points nowhere: {:?}", test1.b);

}

固定到堆上

将一个 !Unpin 类型的值固定到堆上,会给予该值一个稳定的内存地址,它指向的堆中的值在 Pin 后是无法被移动的。而且与固定在栈上不同,我们知道堆上的值在整个生命周期内都会被稳稳地固定住。

use std::pin::Pin;

use std::marker::PhantomPinned;

#[derive(Debug)]

struct Test {

a: String,

b: *const String,

_marker: PhantomPinned,

}

impl Test {

fn new(txt: &str) -> Pin<Box<Self>> {

let t = Test {

a: String::from(txt),

b: std::ptr::null(),

_marker: PhantomPinned,

};

let mut boxed = Box::pin(t);

let self_ptr: *const String = &boxed.as_ref().a;

unsafe { boxed.as_mut().get_unchecked_mut().b = self_ptr };

boxed

}

fn a(self: Pin<&Self>) -> &str {

&self.get_ref().a

}

fn b(self: Pin<&Self>) -> &String {

unsafe { &*(self.b) }

}

}

pub fn main() {

let test1 = Test::new("test1");

let test2 = Test::new("test2");

println!("a: {}, b: {}",test1.as_ref().a(), test1.as_ref().b());

println!("a: {}, b: {}",test2.as_ref().a(), test2.as_ref().b());

}

将固定住的 Future 变为 Unpin

之前的章节我们有提到 async 函数返回的 Future 默认就是 !Unpin 的。

但是,在实际应用中,一些函数会要求它们处理的 Future 是 Unpin 的,此时,若你使用的 Future 是 !Unpin 的,必须要使用以下的方法先将 Future 进行固定:

Box::pin, 创建一个 Pin<Box<T>>

pin_utils::pin_mut!, 创建一个 Pin<&mut T>

笔者补充:若T:!UnPin,但Box< T >是Unpin,因为Box< T >实现了Unpin trait。

【源码补充:impl Unpin for Box<T, A>】

#[stable(feature = "pin", since = "1.33.0")]

impl<T: ?Sized, A: Allocator> Unpin for Box<T, A> {}

固定后获得的 Pin<Box< T>> 和 Pin<&mut T> 既可以用于 Future ,又会自动实现 Unpin。

use pin_utils::pin_mut; // `pin_utils` 可以在crates.io中找到

// 函数的参数是一个`Future`,但是要求该`Future`实现`Unpin`

fn execute_unpin_future(x: impl Future<Output = ()> + Unpin) { /* ... */ }

let fut = async { /* ... */ };

// 下面代码报错: 默认情况下,`fut` 实现的是`!Unpin`,并没有实现`Unpin`

// execute_unpin_future(fut);

// 使用`Box`进行固定

let fut = async { /* ... */ };

let fut = Box::pin(fut);

execute_unpin_future(fut); // OK

// 使用`pin_mut!`进行固定

let fut = async { /* ... */ };

pin_mut!(fut);

execute_unpin_future(fut); // OK

【源码补充:Box<F, A> 】

#[stable(feature = "futures_api", since = "1.36.0")]

impl<F: ?Sized + Future + Unpin, A: Allocator> Future for Box<F, A> {

type Output = F::Output;

fn poll(mut self: Pin<&mut Self>, cx: &mut Context<'_>) -> Poll<Self::Output> {

F::poll(Pin::new(&mut *self), cx)

}

}

【源码补充:&mut T 实现了Unpin】

//https://doc.rust-lang.org/src/core/marker.rs.html#1005

marker_impls! {

#[stable(feature = "pin", since = "1.33.0")]

Unpin for

{T: PointeeSized} &T,

{T: PointeeSized} &mut T,

}

总结

相信大家看到这里,脑袋里已经快被 Pin 、 Unpin 、 !Unpin 整爆炸了,没事,我们再来火上浇油下:)

-

若 T: Unpin ( Rust 类型的默认实现),那么 Pin<'a, T> 跟 &'a mut T 完全相同,也就是 Pin将没有任何效果, 该移动还是照常移动

-

绝大多数标准库类型都实现了 Unpin ,事实上,对于 Rust 中你能遇到的绝大多数类型,该结论依然成立 ,其中一个例外就是:async/await 生成的 Future 没有实现 Unpin,即async 函数返回的 Future 默认就是 !Unpin 的。

-

你可以通过以下方法为自己的类型添加 !Unpin 约束:

- 使用文中提到的 std::marker::PhantomPinned

- 使用nightly 版本下的 feature flag

-

可以将值固定到栈上,也可以固定到堆上

- 将 !Unpin 值固定到栈上需要使用 unsafe

- 将 !Unpin 值固定到堆上无需 unsafe ,可以通过 Box::pin 来简单的实现

-

当固定类型 T: !Unpin 时,你需要保证数据从被固定到被 drop 这段时期内,其内存不会变得非法或者被重用。

-

若T:!UnPin,Box < T > 、&mut T则均实现了Unpin trait。【此处为笔者补充!】

-

当async fn或async block中有参数的生命周期时,此时生命周期也会存储到future当中,这就形成了一个自引用(self-referential)类型。所以需要用Pin。【此处为笔者补充!】

-

Box::pin pins an object to a place in the heap. To pin an object on the stack, you can use the pin macro to create and pin a mutable reference (Pin<&mut T>).

如果想更深一步了解和理解Pin,rust的源码,值得阅读。

【补充】

Macros for pin projection

There are macros available for helping with pin projection.

The pin-project crate provides the #[pin_project] attribute macro (and the #[pin] helper attribute) which implements safe pin projection for you by creating a pinned version of the annotated type which can be accessed using the project method on the annotated type.

Pin-project-lite is an alternative using a declarative macro (pin_project!) which works in a very similar way to pin-project. Pin-project-lite is lightweight in the sense that it is not a procedural macro and therefore does not add dependences for implementing procedural macros to your project. However, it is less expressive than pin-project and does not give custom error messages. Pin-project-lite is recommended if you want to avoid adding the procedural macro dependencies, and pin-project is recommended otherwise.

Pin-utils provides the unsafe_pinned macro to help implement pin projection, but the whole crate is deprecated in favor of the above crates and functionality now in std.

更多推荐

已为社区贡献7条内容

已为社区贡献7条内容

所有评论(0)